May 2004

Office of the Inspector General

Chapter Four

Blake's Misconduct

I. BLAKE'S CAREER WITH THE FBI

Jacqueline Blake was employed by the FBI in the DNAUI and its predecessor unit from August 8, 1988, until her resignation from the FBI on June 7, 2002. Blake has a Bachelor's of Science Degree in Biology from Benedict College in Columbia, South Carolina. She entered duty with the FBI as a Biological Laboratory Technician at the GS-5 grade level and was assigned to the Serology Unit of the Laboratory's Scientific Analysis Section. Her job responsibilities as a Serologist included inventorying and storing evidence and conducting routine evidence examinations to identify the presence of body fluids. Although her early performance appraisals noted that her training comprehension was slower than expected, she received fully successful evaluations or above from her initial appointment until 1994, and she reached the GS-10 grade level in 1991.

The first indications of problems with Blake occurred in 1991. In that year, Blake received an oral reprimand from the DNAUI Unit Chief for abusing her sick and annual leave accounts. She was advised in July 1991 that her leave balances were in deficit and that she could not take additional leave for the rest of the year. Blake nonetheless submitted a leave slip and failed to report to work for one day in November 1991 during an absence of the Unit Chief, even though she was aware that she had no accrued leave. She also took leave for a day in December 1991 without first seeking permission. These events prompted the DNAUI Unit Chief to audit her leave record, which revealed that 37 of her 46 sick leave days occurred either on a Friday, Monday, or the day following a holiday.

Blake's 1992 and 1993 performance appraisals rated her as "exceptional" on all critical elements. In June 1994, however, she received an overall job rating of unsatisfactory. Her performance appraisal stated that her "examinations are not performed according to acceptable laboratory practices," and that she generated false positive serology testing results during proficiency testing and "inaccurate documentation of examinations conducted for blood and semen." Following this evaluation Blake's conduct was monitored intensively for two months, during which time she passed a proficiency test and improved all of her job performance ratings to "fully successful."38 By the end of 1994, Blake received an overall job rating of "superior," a level of performance that she maintained through 1996 when she was promoted to the GS-11 grade level.

Prior to her promotion in 1996, Blake indicated to DNAUI management that she wanted to transfer from serology to DNA analysis work. The Unit Chief at the time recalled that Blake seemed to have confidence problems and that she assigned an Examiner to work with her individually to help with the transition. Blake subsequently received training in the use of the DNAUI's preferred DNA testing methodology at the time, called restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP).39 Blake's 1996 performance appraisal indicates that she demonstrated a "careful attitude" toward her RFLP work and adhered to the applicable protocol. Her 1997 performance appraisal rated her as "exceptional."

In April 1998, Blake was promoted to the position of GS-12 Biologist. In this capacity, she analyzed evidence following its examination by a Serologist and prepared detailed work notes for DNAUI Examiners describing the tests she performed and the results obtained. Over time Blake demonstrated good proficiency in the use of RFLP testing procedures and instructed other Laboratory employees in its use. Her performance appraisals in 1998 and 1999 gave her a summary rating of "exceptional."

In August 1999, Blake began training to become a PCR Biologist. The DNAUI was phasing out its use of RFLP and transitioning to PCR/STR technology. One Examiner, who had provided training to Blake when she was a Serologist, told the OIG that he advised the Unit Chief of DNAUI that Blake should not be allowed to become a PCR Biologist because she lacked the necessary skills. The Deputy Director of the Laboratory told the OIG that it can take up to two years to bring a new PCR Biologist on staff from outside the FBI. Under these circumstances, Laboratory management accepted Blake and thereby minimized a staffing shortage.

Blake took six months to complete the PCR training course, approximately two months longer than average, and her instructor noted that she seemed to have a difficult time with simple math.40 Her PCR training required the completion of three training sets (one each for blood, saliva, and semen), and the processing of ten mock cases. The last mock case was considered a qualifying test for a later proficiency examination. On February 18, 2000, Blake worked on the eighth mock case and, undetected by the Laboratory, failed to process the negative controls. She made the same undetected omission in both her qualifying and proficiency tests, which were administered on February 24, 2000, and March 14, 2000.

Thereafter, Blake assumed her duties as a PCR Biologist, which required her to take cuttings, swabs, or other material containing DNA from the Unit's Serologists and to complete the PCR/STR testing process (i.e., extraction, quantification, amplification, and capillary electrophoresis). Blake primarily worked on the examination team of Alan Giusti, although she also provided assistance to another Forensic Biologist Examiner, and the Manager of the DNAUII Federal Convicted Offender Program.

Blake's 2000 performance appraisal lacked the praise that characterized reviews of her RFLP work. Instead, the appraisal stated that Blake's work was "generally high" and that "she has required fairly extensive supervision to assist her in the decision-making processes that occur during the analysis." Her 2000 and 2001 performance appraisals graded her work as "fully satisfactory" and that she "meets expectations."

In fact, Blake's work in 2000 and 2001 was anything but satisfactory. Without the Laboratory's knowledge, from 2000 to 2002 she failed to process the negative controls in 90 out of 92 cases where DNA was detected on the evidence. Blake's misconduct was not discovered by the FBI until April 8, 2002, more than two years after she began work as a PCR Biologist. She initially denied omitting the negative controls when confronted by Richard Guerrieri, the DNAUI Unit Chief, on April 9, 2002. After that meeting, Blake did not report to the Laboratory again for work.

On May 10, 2002, Guerrieri notified Blake that she would be on leave without pay as of May 19. On June 7, Guerrieri and Joseph DiZinno, the Deputy Assistant Director of the FBI Laboratory (Deputy Director), went to Blake's residence to present a notification document from FBI OPR stating that her conduct had been referred for investigation. They also told her that the OIG was initiating a review of her actions. Blake said that she had thought about the matter and decided to resign. She turned over her credentials and building entry materials to Guerrieri. Blake composed a handwritten resignation letter, effective that day, which she gave to Guerrieri.

The FBI notified the OIG of Blake's misconduct in early May 2002. The OIG began an investigation, and over the next five weeks interviewed Laboratory staff, analyzed documents, and met with representatives of the FBI OGC. On July 11, 2002, an OIG attorney and investigator interviewed Blake at her home. Blake admitted to the OIG that she knew that she was not processing the negative controls that were required by the protocols. She also said she knew she was misrepresenting the status of the negative control samples when she did not properly prepare them for injection but initialed the related injection sheet anyway. On August 23, 2002, Blake executed an affidavit attesting to these facts. The OIG referred the matter to the Department's Public Integrity Section for a prosecution decision. On May 18, 2004, Blake pled guilty in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia to a misdemeanor charge of providing false statements in her laboratory reports.

In her interview with the OIG, Blake explained that she wanted her cases to run smoothly and not to show contamination. Some Laboratory employees have speculated that the reason that she failed to process the negative controls was because she lacked confidence in her ability to master PCR/STR testing methods, which are far more sensitive to contamination than RFLP procedures.

Below we describe in detail Blake's wrongdoing, the impact of her conduct, why she was not detected sooner, and the adequacy of the FBI's response to the discovery that she had failed to process the negative controls in the vast majority of the cases that she handled.

II. BLAKE'S MISCONDUCT

- Incompletely Processed Controls

Blake's misconduct in the DNAUI resulted from her failure to process the negative controls and reagent blanks in accordance with DNAUI protocols. Although she properly prepared these two types of control samples for amplification, she failed to follow established procedures when preparing them for capillary electrophoresis. The effect of this omission has been to render nearly all of Blake's PCR work scientifically invalid.

As required during the extraction and amplification processes, Blake added all the amplification reagents to the negative control tubes and added all the extraction and amplification reagents to the reagent blank tubes. She also amplified the negative controls and reagent blanks as required.

As explained in Chapter Two, Section I.D (Capillary Electrophoresis) of this report, after amplification is complete the protocols require the PCR Biologist to add internal size standard to tubes. Prior to capillary electrophoresis, the PCR Biologist adds an appropriate amount of one of the following to the tubes containing the internal size standard: 1) amplified DNA from reference samples, evidentiary samples, or the positive control; 2) amplified negative control or reagent blank; or 3) an allelic ladder. After performing these steps, the DNA samples, positive control, negative control, reagent blank, and allelic ladders are ready for analysis using capillary electrophoresis.

Blake performed most of these steps as required. However, she failed to add a portion of the amplified negative controls and reagent blanks to the tubes containing the internal size standard. Therefore, the negative control and reagent blank samples that were analyzed through capillary electrophoresis consisted of only the internal size standard. As a result, the negative controls and reagent blanks were useless in detecting contamination that might have been introduced during the testing process. In order for these controls to detect contamination, the amplified contents of the negative controls and reagent blanks must go through capillary electrophoresis.

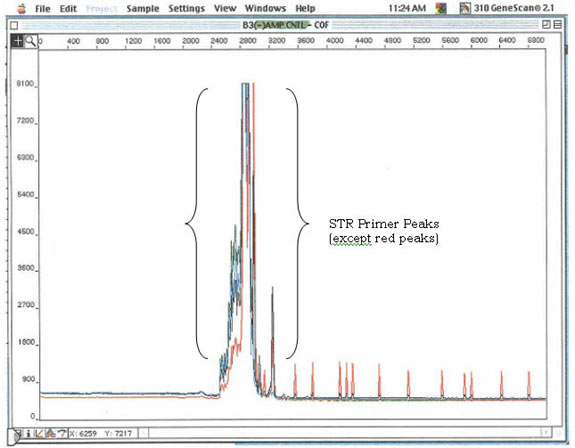

As illustrated below, GeneScan® printouts of the raw collection data for a properly completed negative control include everything detected during capillary electrophoresis, including the primer peaks that result from the reagents used during amplification.

GeneScan® View: raw data for a Negative Control prepared according to protocol.

Peaks depicted in red originate from the internal size standard added to each sample.

When the negative controls and reagent blanks are prepared according to the DNAUI protocols, GeneScan® data will appear similar to the illustration above. During the amplification process, the primers are amplified along with any other DNA in the tube (including any contamination that may have been introduced during the testing process), which allows the primers and the contamination to be detected during capillary electrophoresis.

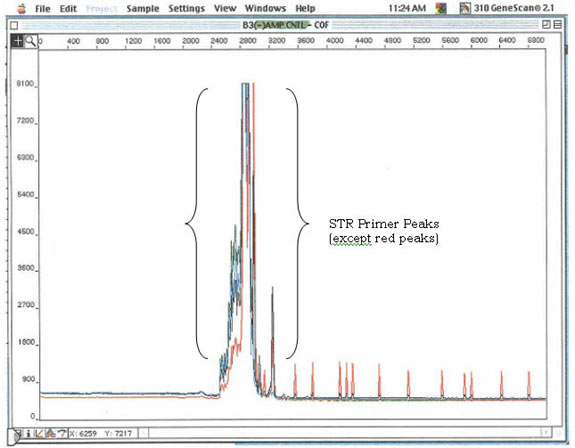

If the PCR Biologist fails to add the appropriate portion of the amplified contents from the negative controls and reagent blanks to the tubes containing the internal size standard, those tubes will not contain any amplified DNA or unused primers, and only the internal size standard will be detected during capillary electrophoresis. Therefore, GeneScan® printouts of the raw collection data for the negative controls and the reagent blanks prepared by Blake do not show the primer peaks, as illustrated below. The red peaks shown on the printout represent only the internal size standard.

GeneScan® View: Negative Control without addition of amplified product

The differences between the graph on the previous page and the graph above are readily apparent. Reviewing GeneScan® data allows the Examiner to determine whether or not the PCR Biologist prepared the samples and controls for capillary electrophoresis in accordance with DNAUI protocols.

The consequence of Blake's omissions is that her testing results are scientifically invalid and cannot be relied upon. Without proper processing of the negative controls and reagent blanks, a Laboratory Examiner is not able to rule out the possibility that contamination, rather than the evidence under examination, is the source of the testing results. By itself, however, the failure to process the negative controls does not change these results or lead to a particular testing outcome (e.g., creating a match between a known and unknown evidence sample). For this reason it is not possible to conclude that Blake intended to manipulate the testing process to implicate or to absolve individual defendants. The retesting of evidence in Blake's cases to date indicates that the DNA profiles that she generated were accurate.

Before Blake's misconduct was discovered, the DNAUI's policy called for Examiners to review only the Genotyper® printouts for the negative controls and reagent blanks to ensure contamination was not introduced during the testing process. This policy of not reviewing GeneScan® data allowed Blake's misconduct to continue undetected for approximately 25 months, since the Genotyper® data displays the message "No Size Data"41 both for properly completed negative controls and reagent blanks that reflect no contamination (the desired result), as well as when no amplified product has been added (what Blake did). An example of this message appears in the following Genotyper® graph:

Genotyper® View: COfiler Ladder

with Positive Control Allele Call

[Image not available electronically] |

Thus, the only way to determine if the controls and samples are prepared properly for capillary electrophoresis is to review GeneScan® data that displays what the capillary electrophoresis detects. After Blake's misconduct was discovered, the DNAUI changed its policy to require Examiners to review GeneScan® data to ensure that the negative controls and reagent blanks are prepared properly.

- Falsification of Laboratory Documents

In accordance with DNAUI protocols, Blake initialed each page of the case file documentation (including DNA analysis results) that she created. See generally Section 11.2.3 of the DNA Analysis Unit I Quality Assurance Manual (version. 7.28.00)(describing DNAUI initialing procedures).42 A DNAUI employee's initials confirm his or her involvement in the processes and procedures described in the documentation. Id. Moreover, statements provided by Laboratory personnel, including Blake, indicate that DNAUI employees understood at the time of Blake's misconduct that an employee's initials at the bottom of a case file document signify that the work described is complete and accurate. By providing her initials in cases where she did not perform the requisite control testing, Blake falsified laboratory documents. As Blake has stated to OIG investigators, she knowingly misrepresented her work in Laboratory documents that she knew other DNAUI employees would rely upon to verify that she had complied with applicable procedures and protocols. According to Blake's signed, sworn statement to the OIG:

During the OIG interview, I reviewed some documents that came from the file for Lab #991005047 GL FY. Included in those documents was an Injection List. The Injection List was prepared by me and lists the injections that the CE [capillary electrophoresis] machine was programmed to run in connection with the specific Lab Number. The Injection List that I reviewed was initialed by me in the lower left corner. These initials indicate that I generated the paper work and properly completed the preparation of the samples listed on the document for injection, including the negative controls. I knew that DNA Forensic Examiner Giusti, in this case, would have relied on this initialed Injection List as proof that all protocols were followed in processing the samples on the list. I knew that when I did not properly prepare the negative control samples for injection but initialed the related injection sheet anyway, I was misrepresenting that the negative control samples were properly prepared for injection and properly run on the CE machine. I also knew that no one routinely checked the raw data that would show the absence of the primer peaks for the negative controls.

Because she was not processing the negative control samples, Blake never had a need during her tenure in the DNAUI to record an entry in the Unit's contamination log. Yet, despite her prior training and performance problems, Blake's noteworthy and unusual record of contamination-free testing did not result in heightened scrutiny from Laboratory management.

- The Impact of Blake's Misconduct

Our investigation of Blake's misconduct has not revealed any instances where Examiners from the FBI Laboratory presented erroneous DNA testing results in court based upon Blake's faulty STR analyses. Notwithstanding this fact, with the exception of 2 cases where she processed the negative controls and 11 cases where no DNA was found, Blake's misconduct has rendered over two years worth of her STR work scientifically invalid and unsuitable for use in court, requiring the FBI Laboratory to repeat DNA testing in her cases.43

Although the FBI Laboratory has yet to identify any cases where retesting did not confirm the accuracy of Blake's DNA profiles, we found that her actions caused significant adverse effects in at least five respects: 1) it required the removal of 29 DNA profiles from NDIS, 20 of which have yet to be restored;44 2) it delayed the delivery of reliable DNA reports to contributors of DNA evidence in Blake's cases; 3) her testing consumed all the available DNA evidence in several cases, leaving only her suspect DNA profiles as a basis on which to draw conclusions; 4) the corrective action necessary to address Blake's misconduct has consumed substantial resources of the FBI Laboratory and DOJ, as well as the resources of state and local investigators and prosecutors who were notified of her misconduct and had to take corrective measures in their cases; and 5) the controversy surrounding Blake has caused some measure of credibility loss to the FBI Laboratory.

After Blake's actions were discovered, the DNAUI notified the Forensic Science Systems Unit (FSSU)45 within the Laboratory, which removed 29 profiles that Blake processed through STR analysis from NDIS. This work was completed by May 2002. As of March 2004, the Laboratory had retested and restored nine profiles; no DNA remains for further analysis in two cases.46 The Laboratory recently obtained contractor support to assist with evidence retesting in Blake's cases, and informed the OIG in October 2003 that it expected to restore the remaining profiles to NDIS by the end of March 2004. Until these profiles are restored there will be an ongoing risk that an investigative agency will submit a DNA profile and not generate a match with a corresponding Blake profile because the Blake profile has been removed from NDIS. Consequently, past crimes may remain unsolved.

Blake's misconduct also has delayed the delivery of reliable DNA reports to evidence contributors and wasted limited evidence samples. The Laboratory is attempting where feasible to obtain from contributors new evidence samples that Blake did not handle. In addition, in several cases Blake's faulty STR analysis is the only DNA information that is available. As with the two NDIS profiles described above, the earlier submitted evidence was consumed in the testing process and new evidence samples cannot be obtained.

Blake's misconduct also has adversely impacted the resources of the FBI and DOJ. The efforts that the FBI Laboratory and DOJ have had to expend on the corrective measures needed to address Blake's actions have been substantial. Both organizations have devoted thousands of hours of work to deal with the consequences of Blake's failure to comply with the DNAUI's protocols, a cost that does not include the funding expended for contractor support to retest evidence. The DNAUI Unit Chief estimated that in the year following the discovery of Blake's wrongdoing, he devoted more than half of his time working on Blake-related issues. The FBI's OGC and the DOJ's Counterterrorism Section have had to track legal proceedings in her cases and have issued dozens of notification letters to contributors explaining the possible ramifications of her actions. U.S. Attorney's Offices have had to respond as well. Blake's conduct has been put at issue in federal criminal litigation through challenges to the admission of her work into evidence and to the integrity of DNA evidence generally.47

Lastly, we believe that Blake's misconduct, and the Laboratory's failure to detect it for a period exceeding two years, has damaged to some extent the credibility of the FBI Laboratory. Media reports of the Blake matter described her actions in the context of past and ongoing problems at the Laboratory.48

- Why Blake Was Not Caught Earlier

- The Detection of Blake's Misconduct

The discovery of Blake's misconduct was inadvertent. On Friday, April 5, 2002, a senior DNAUI Biologist and Blake's former PCR/STR instructor was waiting on her capillary electrophoresis machine to generate data when she happened to glance at Blake's machine, which was nearby. The Biologist noticed that the information displayed was not consistent with the proper processing of STR negative controls because the primer peaks were absent. She asked Blake the next time she saw her about the data stream that her machine had generated, and Blake provided a nonchalant response that heightened the Biologist's curiosity. She had expected Blake to explain that she had erred in her preparations for the electrophoresis; instead Blake indicated only that the configuration of the displayed data was not a problem.

On Monday, April 8, 2003, the Biologist shared her concerns about Blake during lunch with a fellow Laboratory Biologist. Later that day, the first Biologist examined the underlying data for several of Blake's completed DNA profiles and discovered that the negative controls had not been processed. That evening, the Biologist telephoned her supervisor, the Unit Chief of DNAUI, Richard Guerrieri, at his home and told him of her findings. Guerrieri immediately recognized the potentially serious consequences if the Biologist's observations proved to be accurate.

Upon learning of the Biologist's concerns, Guerrieri contacted Blake's immediate supervisor, Forensic Biologist Examiner Alan Giusti. Guerrieri advised Giusti of the potential problem and directed him to conduct an "immediate and expeditious review" of multiple electronic raw data files for current cases to attempt to determine the nature and extent of the problem.

The next day Giusti identified several case files for review and examined them. He advised Guerrieri that there was "unacceptable performance of negative controls within the selected case files."49 Guerrieri then reviewed the data collected by Giusti and concluded that there appeared to have been a systemic omission of the negative control within Blake's casework. With this finding, Guerrieri decided to notify then Acting Assistant Director of the Laboratory Division, Dwight Adams, of the situation.50 Guerrieri did so the same day, April 9. Adams advised Guerrieri to pursue the matter as a "technical issue" unless circumstances warranted otherwise, and to interview Blake and attempt to ascertain the scope of the problem. According to Guerrieri, a "technical issue" is something that is not the result of a deliberate act. Guerrieri and Giusti also met with Blake on April 9 and she falsely stated that she had followed all required steps in processing her samples, though she may have made a few mistakes. Guerrieri informed Blake that until the technical issue was thoroughly evaluated and resolved, she was restricted from casework examinations and was not authorized to perform any further analyses.

- How Blake Avoided Detection

We do not believe that Blake's success at escaping detection for over two years can be attributed to a lack of oversight by any one individual. Rather, Blake was not discovered earlier primarily for two reasons: 1) she was adept at lying to her supervisors; and 2) the DNAUI had in place a shortsighted policy that failed to require Unit Examiners to routinely scrutinize GeneScan® data.

Blake's willingness to lie to her supervisors coupled with the lack of review of GeneScan® data proved effective in concealing her failure to process the negative controls. Her affidavit to the OIG is clear that she knew exactly what she was doing when she initialed the CE injection sheet: she was misrepresenting to her supervisors that she had performed testing procedures that she in fact had omitted.

Blake also was fully aware that by not processing the negative controls and initialing the CE injection sheet she was taking advantage of a loophole in the Laboratory's procedures with respect to GeneScan® data. She told the OIG that she "knew that no one routinely checked the raw data." The DNAUI's standard operating procedures thus allowed Blake to carry out her misdeeds without discovery.

Moreover, the ease with which Blake escaped detection was facilitated by the Laboratory's failure to scrutinize her work in a manner that took into account her documented record of evidence handling problems and her prior training difficulties. Both during and after training to become a PCR Biologist, Blake received the same degree of oversight as a Biologist with an unblemished record. The Examiner for whom Blake worked most often, Alan Giusti, told the OIG that he was not aware of Blake's prior performance issues until after she was caught. He also did not know that one of his colleagues, who previously had trained Blake, had recommended that she not be permitted to become a PCR Biologist. The same individual refused to participate in her PCR training. Further, Blake's record of contamination-free testing for more than two years did not receive scrutiny. Laboratory personnel explained they thought that it was inconceivable that a fellow employee would not process the negative controls and therefore her failure to appear in the DNAUI's contamination log did not heighten scrutiny of her actions.

III. THE FBI'S RESPONSE

After the FBI Laboratory discovered Blake's omission of the negative controls, it worked quickly to determine the scope of the problem and to fashion a remedy to prevent its reoccurrence. The DNAUI isolated all of Blake's PCR/STR cases and performed case file reviews to determine if comparable misconduct had been committed by other DNAUI staff members. These initial remedial actions later were combined with efforts to repair the damage that Blake inflicted on the individual cases that she processed. We believe that, with some exceptions, the FBI's early response to Blake's misconduct was appropriate and timely. Our review revealed, however, that after the initial response, the pace of evidence retesting in the cases that Blake handled and of the Laboratory's notifications to evidence contributors and prosecutors has been problematic.

- Initial Remedial Actions at the Laboratory

The Laboratory's initial remedial actions largely took place within the confines of DNAUI and were implemented under the supervision of Richard Guerrieri, the DNAUI Unit Chief. By April 15, 2002, Guerrieri was convinced that the lack of negative control data in Blake's work was not the result of equipment failure or other accident. Effective that day, he implemented a new policy requiring DNAUI STR case documentation to include hard copies of the electronic raw data files for all casework samples that depicted a negative result. In addition, the new policy provided that the STR documentation must be reviewed by the reporting Examiner and confirmed by a second Examiner. The decision also was made to limit the scope of the Laboratory's initial inquiry to the testing that Blake had performed as a PCR Biologist and not to examine her serology and RFLP examinations.51 The DNAUI collected all the electronic raw data from Blake's STR tests and the training program files that she had completed.

By April 30, all of Blake's STR casework for Giusti and a second Examiner had been identified and was being categorized through the following priority system: reported inclusions (i.e., matches with known DNA samples), reported exclusions (i.e., elimination of match possibility with known DNA samples), and inconclusive results. This analysis led to the creation by early summer 2002 of a database of Blake's STR cases, which included information such as whether a DNA report had been issued from the DNAUI and the case status (i.e., phase of DNA testing). In all, Blake's STR analyses were identified in 103 cases. Of these, no DNA had been identified in 11 cases, Blake failed to process the negative controls and reagent blanks in 90 cases, and she properly performed the tests in 2 cases. Out of the 90 cases in which Blake failed to process properly the controls, DNA analysis reports were sent to evidence contributors from the DNAUI in approximately 45 cases.

Guerrieri also developed a sampling plan to determine whether other biologists in the DNAUI failed to conduct the negative control tests. Ten active case files from each DNAUI PCR Biologist were scrutinized by the Unit's Examiners. All files, except those for Blake, indicated that the negative control specimens had been processed. Based on this evidence, the Laboratory concluded that the omissions in question were limited to Blake.

In addition to work within the DNAUI, Guerrieri promptly notified other units within the Laboratory of the Blake situation. On April 15, he spoke with John J. Behun, Chief of the FSSU and NDIS Manager. Behun concluded that all DNAUI specimens that Blake processed through STR analysis that were entered into NDIS should be identified and removed and placed into a temporary target batch file until the matter was resolved. This work was completed by early May 2002, and 29 profiles were removed from NDIS. DNAUI agreed to notify the FSSU of any confirmed NDIS matches involving DNA profiles generated by Blake and other NDIS contributors, to inform those contributors of the problem, and to attempt to reanalyze the negative control specimens and/or the remaining physical evidence. The DNAUI subsequently identified a single match through NDIS that had been generated by an external lab prior to the removal of Blake's profiles.52

Guerrieri also met with the DNAUII Unit Chief. In addition to her casework, Blake had performed STR analyses on some reference blood samples from incarcerated individuals within the Federal Convicted Offender Program managed by a DNAUII Examiner. Guerrieri and the DNAUII Unit Chief agreed that these samples should be located and retesting performed where appropriate.53

The Laboratory also sought guidance from FBI Headquarters, including the FBI's OPR and OGC. In mid-April, Adams met with Michael DeFeo, Assistant Director for OPR, and agreed that the Laboratory would forward documentation describing Blake's conduct to OPR for review. DeFeo advised Adams that the matter would have to be referred to the OIG. Guerrieri and DiZinno subsequently met with an OPR Unit Chief to brief him on the Blake matter. DiZinno said that the Laboratory hoped to receive guidance on what corrective actions should be implemented, including whether the Laboratory needed to evaluate Blake's serology and RFLP work. The OPR Unit Chief told them to furnish him with a written report outlining the misconduct allegations and the actions taken by the DNAUI in response to the discovery of the misconduct. On April 30, 2002, the Laboratory provided a 6-page memorandum to the FBI Director, with a copy to OPR, that described Blake's actions.

On May 7, 2002, OPR forwarded Guerrieri's April 30 Memorandum to the OIG, which began an investigation. As mentioned earlier, over the next five weeks OIG staff interviewed Laboratory personnel, examined documents, and met with representatives of FBI OGC. At a meeting on May 21, 2002, OGC explained that it would be heavily involved in the FBI's notifications to prosecutors, including providing legal guidance, and that the Laboratory would manage the Bureau's response to the Blake matter. The OGC and OIG agreed that the OIG would not be involved in managing the FBI's activities, though information would be shared to ensure that there was no interference with the OIG's investigation. The FBI OGC also explained that a management plan would be developed.

Following these developments, the DNAUI focused some attention on its operating procedures. In July 2002, as part of the Unit's annual review of its protocols, Guerrieri requested that DNAUI program managers take into account Blake's misconduct when formulating proposed protocol revisions. However, other than the requirement that GeneScan® data be included in the case file for review by the Examiners, Guerrieri did not receive any suggested modifications to the protocols from his staff. In addition, later that year Guerrieri initiated a project to map case processes in the DNAUI to facilitate communications and decision-making. See generally Chapter Five, Section III.A.2 (describing need for decision aids).

- Identification and Processing of Cases That Required Corrective Action

After the FBI Laboratory took action to remedy the processing of negative controls in the DNAUI, its focus turned to correcting the damage that Blake caused in the cases she handled. This task has proved difficult for the Laboratory. For example, the majority of the evidence that required retesting in Blake's cases remained unevaluated over 23 months after her misconduct was detected and, in some cases, the Laboratory's testing has not been completed even though the evidence was submitted to the Laboratory over four years ago.54 Moreover, as of March 2004, nearly half of the evidence contributors in cases where Blake failed to process the negative controls have not received written notification that Blake's misconduct impacted their evidence.

- Early Reaction and Planning

One of the most pressing issues for the DNAUI after the discovery of Blake's misconduct was to identify the cases where an Examiner had relied on Blake's analyses and subsequently issued a report to a requesting party, and then to ascertain the status of legal proceedings in those cases. Completion of this work was not easy, however, because the Laboratory did not have a system to track legal proceedings after its findings were disseminated. As with many other issues, the formulation of the Laboratory's response to this problem was left to DNAUI Unit Chief Guerrieri and his staff. With Guerierri's oversight, the Laboratory established a database of Blake's cases in early summer 2002 to track its remedial work and to stay abreast of case developments.

Guerrieri met with an FBI Assistant General Counsel on April 10, 2002, two days after the discovery of Blake's actions, to inform her of the Blake problem.55 From the outset OGC recognized the potential gravity of the situation. The OGC lawyer e-mailed her supervisor on April 15 and explained as follows:

There is a major problem brewing in DNA Unit I that concerns a technician's work in preparing cases for the overall review of an examiner. They don't yet know the dimensions of the problem - it could be huge - implicating all of the cases of examiner Alan Giusti and other examiners as well, for years. They don't know if mistakes were purposeful or inadvertent, but they may threaten the integrity of our results across the board (Technicians do most of the underlying bench work and examiners make the conclusions and write the reports). They are in the process of doing a review to try to ascertain the scope of the problem and whether it implicates other technicians as well (which they don't think it does). They have not yet notified OPR but they have taken the technician off cases immediately.

We may need a task force on this one - perhaps drawing from ASCLD-LAB expertise, and/or others out there in the forensic community. It's too early to tell anything just yet . . . .

Approximately one month later, OIG staff who were investigating Blake's actions met with OGC staff members and were told a management plan would be developed to guide the FBI's response to Blake's failure to conduct the required contamination testing and that it would be shared both with the OIG and the Office of the Deputy Attorney General. The OIG similarly was advised by the OGC Assistant General Counsel in May 2002 that "a policy will have to be arrived at in concert with the Lab." With the exception of the April 30, 2002, memorandum from the Laboratory to the FBI Director described supra, which the Laboratory explained to the OIG was its initial strategy, Laboratory management has acknowledged that no planning material was created to guide its remedial activities and to coordinate the work of the DOJ and FBI personnel working on the Blake matter.56 Our review of documents furnished by the FBI, including e-mails, did not reveal any communications that outlined prospectively for the various participants what the FBI's response should entail, what the various participants were tasked to complete and, as appropriate, by when. In addition, in November 2002, the OGC Assistant General Counsel advised the OIG that no policy had been formulated for what she described then as a "fairly fluid" situation.

According to Laboratory employees, throughout the Spring and Summer of 2002 Laboratory management regularly discussed with the OGC how to proceed. The Laboratory Director explained that initially he held regular meetings with his staff to address Blake-related issues. The Department was not directly included in these meetings though, and the Laboratory Director explained that he has never spoken to the DOJ contact who the Criminal Division assigned to track developments in the Blake matter - Barry Sabin, the Chief of the Counterterrorism Section. According to Sabin, his role was to learn the facts of the Blake case, to identify any legal issues that required attention and advise the FBI accordingly, and to monitor the FBI's response on behalf of DOJ.57 The Laboratory Director further stated that he did not know what exactly the Counterterrorism Section was doing.58 He also added that he has not asked anyone for an explanation of what the Counterterrorism Section's role is. He stated that he relies upon OGC to provide the Laboratory with pertinent guidance. Other Laboratory employees explained that they were surprised that there was not more direct contact with DOJ personnel. One senior FBI manager told the OIG that there was no leader overseeing the response of the FBI and DOJ to the problems caused by Blake's misconduct, and that was a problem because no one was in charge to coordinate activities.

- Notifications

After the Laboratory determined that the failure to process the negative controls was limited to Blake and that her omissions were not the result of a technical defect, Laboratory management decided, with OGC assistance, to notify appropriate contributing agencies and/or prosecuting attorneys of the limitations regarding Blake's STR analyses. Additionally, Laboratory management decided that all trials in which Giusti had previously offered expert testimony regarding STR analyses based upon Blake's work would be identified, the resulting electronic data files reviewed, and appropriate officials notified if unacceptable performance of negative control specimens was detected.59 By April 30, 2002, the Laboratory had completed identification of Blake's STR analyses for Examiners Giusti and Garvey and had developed a priority notification scheme that accounted for various case considerations, including whether the DNAUI previously had provided testimony, trial status, terrorism linkages, and whether suspects had been identified. At approximately the same time Giusti began notifying evidence contributors by telephone of the situation; he also conferred with case prosecutors.

During May 2002, Guerrieri worked with OGC to create a notification letter for DNA contributors. Sabin began to assist the FBI with contributor notification and other issues at this time. He reviewed and provided input on the draft notification letter that Guerrieri and OGC had prepared.

On June 5, 2002, the first notification letters, signed by the Laboratory Director, were sent to 25 DNA contributors and prosecutors who had received a DNA report from the DNAUI. The letter stated cryptically that "some of the control samples were not processed to completion" during the DNA analysis and that the "DNA testing results reflected in [the issued report] should not be used for investigation or prosecution purposes until such control samples have been evaluated and determined to thoroughly satisfy established requirements." The letter requested that the contributor resubmit the evidence for additional analysis. The OIG subsequently raised concerns about these letters primarily because they failed to explain Blake's conduct adequately.

Additional notification letters signed by the Laboratory Director were sent in July and October 2002 to 44 contributors and prosecutors. These letters contained the same language used in the Laboratory's June letter, and were not sent consistently to associated prosecutors. According to one Laboratory employee, OGC became much more involved in notification and case tracking issues beginning in October 2002. A new OGC attorney was assigned that month to handle the Blake matter. The OIG was able to verify that OGC delivered 71 letters covering 56 cases to contributors and prosecutors in late November and December 2002,60 many to the same contributors who received earlier notification from the Laboratory.61 OGC's notification letters described Blake's misconduct, the function of negative controls, and the initiation of the OIG investigation. It also requested the addressee to resubmit evidence for testing and to share a copy of the notification letter with any prosecutors who were working on cases to which the previously submitted evidence related.

The Counterterrorism Section at DOJ also assisted the FBI to inform DNA contributors and prosecutors of the Blake matter by issuing letters supplementing the information contained in the FBI's notifications. Between July and September 2003, the Counterterrrorism Section sent out 27 letters to prosecutors and contributors and has issued another 2 since that time. Following discussions with prosecutors in Blake's cases, the Counterterrorism Section focused its notifications on matters where the possibility remained for Blake's DNA analyses to be relied upon in future investigative activities and/or court proceedings. The Counterterrorism Section prepared different letters depending on whether Blake's conduct previously had been disclosed to defense counsel. These letters emphasized disclosure obligations, that Blake had custody and control over the original submitted evidence that was used to conduct the initial DNA analysis, and that there was no indication that Blake failed to abide by any Laboratory protocols in the DNAUI other than those regarding the processing of control samples. The Executive Office for United States Attorneys also issued an 8-page guidance document regarding the Blake matter in June 2003 to all United States Attorney's Offices based on legal analysis performed by the Counterterrorism Section.62 That document addressed a host of different legal issues implicated by Blake's conduct, including chain-of-custody and ethical considerations, and was included by the Counterterrorism Section in its correspondence to DNA contributors and prosecutors.

Despite these efforts, as of February 2004, DNA contributors in 42 cases still had not received written notification that Blake had failed to process properly the evidence they had submitted. Of this number, 20 contributors received no notification at all concerning Blake's handling of their evidence. Of the written notifications provided, in some situations as many as three letters have been sent to the same individual. See further discussion in Chapter Four, Section IV.

- Evidence Retesting

In addition to its efforts to notify DNA contributors about the Blake problem, the Laboratory developed procedures to provide contributors with retesting of evidence. Initially Guerrieri, with the approval of Adams, opted to process only the negative controls that Blake had not completed. By late June or early July 2002, however, Guerrieri determined that full retesting of all samples in Blake's STR cases in which the negative controls had not been run was required to ensure technically valid results that could be used as evidence. Early testing of the uncompleted negative controls had resulted in the discovery of DNA contamination in some samples, while other analyses were missing a quantification step. Under these circumstances, and based on Guerrieri's recommendation, Adams opted for full retesting.63 According to Guerrieri there was no discussion whether this decision had legal ramifications, and if so, what they might be.

The Laboratory also decided in Spring 2002 to perform the retesting itself rather than attempt to out-source the work to a contractor. According to one Laboratory employee, this decision was made within days of learning of Blake's misconduct. The decision also was made despite the fact that the Laboratory was faced with a substantial backlog of cases in the DNAUI. According to DiZinno, the Laboratory had, and continues to have, an unacceptable turnaround time processing evidence, especially in the DNAUI. By December 2002 the DNAUI recognized that it could not complete the retesting of Blake's cases in a timely manner. It thereafter reversed course and entered into contracts in September 2003 to have the evidence in Blake's cases retested by private laboratories. The Laboratory stated in early 2004 that it expected to have this work completed by the end of March 2004. DiZinno acknowledged to the OIG that the Laboratory underestimated the time it would take to retest Blake's evidence and that the pace of retesting has been problematic.64 As of February 2004, evidence retesting had been completed in only 27 out of the 90 cases where Blake failed to process the negative controls, and 20 of the original 29 profiles removed from NDIS still have not been restored.65

IV. OIG ANALYSIS

Our examination of the FBI's response to Blake's misconduct revealed that the FBI Laboratory worked quickly to determine the cause of the negative control omissions in Blake's cases and whether other biologists in the DNAUI had experienced the same problem. After the Laboratory confirmed that the failure to process the negative controls was limited to Blake and not due to technical causes, such as equipment failure, it self-reported the facts and circumstances regarding her misconduct to the FBI OPR and sought guidance on how to fashion a proper response. OPR advised the OIG of the matter approximately one month later.66 The DNAUI also promptly closed the loophole in its procedures that allowed Blake to escape detection for over two years: it required GeneScan® data to be included in the case file and reviewed by two Examiners. The effectiveness of the Laboratory's early response to Blake's wrongdoing was due largely to the efforts of the DNAUI Unit Chief, Richard Guerrieri, and his staff, who deserve credit for these actions.

However, our review identified other issues of concern regarding the FBI's response to Blake's misconduct. These include: 1) the timeliness of the retesting of evidence and of written notifications to DNA contributors and prosecutors; 2) the legal analysis provided by the FBI OGC in the months immediately following the discovery of Blake's misconduct; and 3) the scope of the Laboratory's remedial actions. We also believe that given Blake's prior work history and training experiences, the Laboratory should have paid more careful attention to her performance on her initial PCR qualifying and proficiency tests and on the first several profiles she generated after she became a PCR Biologist.

- Timeliness of Evidence Retesting and Notifications

The retesting of evidence in Blake's cases has taken too long. The Laboratory's Deputy Director told us that he was not satisfied with the pace of the retesting, and the DOJ Criminal Division echoed the same concern in an October 2003 letter to the Laboratory Director that requested that evidence retesting "be conducted in an expedited fashion."67 Given that the Laboratory has a goal of 60 days for each unit to process its evidence, and that the DNAUI has taken over 2 years to complete its reanalysis in many of Blake's cases (and in some matters over 4 years for the Laboratory to complete all requested analyses), we think it is self-evident that the pace of retesting has proceeded far too slowly.68

Several factors have contributed to the delays, including events beyond the Laboratory's control, such as the responsiveness of contributors to resubmit their evidence. The delays have been significantly exacerbated, however, by a decision the Laboratory made soon after Blake's detection. Although the DNAUI at the time had a substantial backlog of cases to analyze, and historically has been a bottleneck in the Laboratory's processing of evidence, Laboratory management opted not to seek contractor assistance with Blake's cases and instead attempted to complete the reexaminations itself. The result was that the Laboratory had less than ten cases retested by the end of 2002; it was only at that point that the decision was made to seek contractor support. The Laboratory entered into two contracts in September 2003 with private laboratories to retest the balance of evidence in Blake's cases.

We believe that the Laboratory failed to analyze properly whether it could absorb the additional retesting work and complete it in a timely fashion. The backlog of unprocessed DNA evidence and manpower constraints should have alerted the Laboratory to the need to seek outside assistance sooner than December 2002. The consequence of this decision is significant. The Laboratory's failure to seek the necessary resources promptly heightened the risk that a criminal would avoid identification because his or her DNA profile, which otherwise would be available but for Blake's misconduct, is not included in the appropriate DNA databases for law enforcement agencies to search.

Similarly, we are concerned with the time it took for the attorneys who worked on the Blake matter to generate a sufficient notification letter, and that nearly two years after the discovery of Blake's misconduct there were still 42 cases where evidence contributors had not received a letter notifying them that Blake had failed to process properly the evidence that they submitted. After the Laboratory issued its first letters in June 2002, which FBI OGC and the DOJ Counterterrorism Section worked on jointly, the OIG questioned the sufficiency of the notification. In our view, the June letter failed to describe adequately what Blake did. The Laboratory, however, continued to issue notification letters in July and October 2002 with the same language as the June letter.69 FBI OGC began issuing its own notification letter to contributors and prosecutors in late November 2002 that described Blake's misconduct and was drafted largely by OGC supervisors. We believe that this letter was sufficient to alert evidence contributors and prosecutors to Blake's misconduct such that proper disclosures could be made.70 We are concerned, however, that the Laboratory's letters were not sent or copied to all associated prosecutors.

Within the first two months following Blake's detection we believe that the OGC staff attorney assigned to the Laboratory should have prepared a notification letter comparable to the one that was sent by OGC in November and December 2002, and that the written notification should have been completed by mid-summer 2002 at the latest. These letters should have been delivered to all evidence contributors and their associated prosecutors. Although we did not find case-related prejudice resulting from the timing of the notifications, we believe that the Blake matter required earlier and more complete notification than was provided.

We also are concerned that nearly two years after Blake's detection, DNA contributors in 42 cases had not received written notification that Blake had failed to process properly the evidence they submitted, and 20 of these contributors received no notification at all concerning their evidence. According to the FBI, with two exceptions the cases where notice has not been furnished are ones in which no report was issued from the DNAUI and no suspect has been identified. The FBI also has explained that the individuals who submitted the evidence in these cases have not contacted the Laboratory to inquire about the evidence, possibly indicating that the case in question is inactive. Although 11 of the 20 cases in which no notice was provided originated either from the Washington Field Office of the FBI or the Washington Metropolitan police, which received written notifications of Blake's wrongdoing in other cases as well as other communications about her misconduct,71 we believe that all evidence contributors and associated prosecutors should have been notified directly in writing during the summer of 2002 that Blake had failed to process their evidence properly. At that juncture the evidence contributor would have had the ability to make an informed decision whether to resubmit new evidence or to seek testing services from another source. Because 20 of these contributors were not informed, however, they were deprived of the opportunity to make this decision. Moreover, we believe that the failure to provide these notifications by this date violated the spirit of the message that the Laboratory conveyed to the FBI Director and FBI OPR in its April 30, 2002, memorandum in which it explained that "[w]ith the assistance of the OGC, the LD [Laboratory Division] will notify all appropriate contributing agencies and/or prosecuting attorneys of the technical issue and potential limitations regarding the STR analyses conducted by Ms. Blake." The Counterterrorism Section also informed the OIG that it encouraged the FBI to make full and complete written notifications to all evidence contributors and associated prosecutors.

We further believe that the timeliness of the FBI's evidence retesting and notifications was hindered by the Laboratory's failure to maintain written planning materials and to disseminate them to officials who were assisting the Laboratory with the Blake problem. The FBI was unable to identify any document for us that set forth prospectively for Laboratory staff members the steps they should take to address Blake's misconduct and the timeframes contemplated to complete particular tasks. OPR asked for a written plan, and the Laboratory should have updated its April 30 memorandum as time progressed and shared it with others. FBI OGC explained to the OIG in May 2002 that a management plan would be created to guide the response over time and that it would be shared with the OIG and the Office of the Deputy Attorney General. Such a plan was never developed, and the consequence was unnecessary inefficiencies and delay.

We believe that had the Laboratory prepared a management plan, it would have diminished the likelihood that three entities - the Laboratory, FBI OGC, and the Counterterrorism Section - all would need to send out notification letters. It also may have triggered more careful analysis regarding the decision to keep the retesting of evidence within the Laboratory rather than seeking a contractor to assist with the work. This plan should have tasked the FBI OGC attorney assigned to the Laboratory with specific notification-related assignments and coordination responsibilities. It also should have identified milestones for the evidence retesting and triggers for the reevaluation of the need for contract support.

We are also troubled that Laboratory management at the highest levels seemed disinclined to seek out DOJ's views and to coordinate its planning activities with DOJ. Adams stated that the Laboratory Division at the FBI was "in charge" of the Blake situation, but at the same time he explained that he didn't know what the Counterterrorism Section was doing. We believe that if that were the case, the Laboratory Director should have reached out to DOJ to understand its views on the Blake problem, and if the Laboratory and DOJ had differing priorities, these should have been identified, discussed, and reconciled at the earliest possible moment. We believe that DOJ made it clear to FBI OGC that it wanted fuller disclosures and more information provided to contributors and prosecutors. DOJ pressed for more expedited evidence retesting. The Laboratory was slow to respond, with the result that two years after Blake's detection, evidence still is waiting to be retested and many evidence contributors still do not know that their evidence was improperly processed by Blake.

- The Sufficiency of Legal Services Provided to the Laboratory in the Months Following Blake's Detection

We also question the relationship between the Laboratory and FBI OGC in the months following Blake's detection. Blake's misconduct required the Laboratory to address numerous issues, such as what the permissible uses are of Blake's corrupted profiles and how to conduct the retesting of evidence. Indeed, in the initial aftermath of Blake's discovery, the Laboratory needed assistance merely to determine what the issues were that needed to be evaluated and resolved.

The OIG's interviews with the Assistant General Counsel from OGC who handled the Blake matter from April to November 2002, and others have led us to conclude that the Laboratory did not receive the quality of legal services that one would expect from FBI OGC, and Laboratory management was not sufficiently assertive when soliciting legal advice. In our view, substantial effort was required at the outset of the Blake matter to: 1) learn the underlying facts, 2) identify and organize the legal issues that those facts implicated, 3) analyze and explain to the Laboratory the legal principles that were pertinent to the issues in question, 4) present the litigation risks and legal policy considerations associated with particular courses of action available to the Laboratory, and 5) highlight pitfalls or issues of special concern that warranted the Laboratory's attention.

Both the Laboratory and OGC explained that no meeting was ever held to brief the FBI Laboratory on the legal considerations described above or to present the findings and conclusions of any legal research. Indeed, the OGC attorney told us that she did not conduct any legal research. No memoranda were prepared for the Laboratory and our review of the Assistant General Counsel's case file did not reveal any documents, including e-mails or notes, that set forth substantive legal analysis or otherwise identified the issues and organized them in a way that would be comprehensible to the Laboratory. Disclosure issues were obvious from the outset, but there were others that should have been addressed in a meaningful way much earlier than they were, such as what was permissible with the off-loaded NDIS profiles and chain-of-custody issues. The Assistant General Counsel's response to our questions on several occasions was that we did not understand the way FBI OGC operated. She further explained that she is a traditional counselor at law who rendered advice based largely on past experience: someone posed a question and she provided an answer.

This approach was ill-suited to the complexities of the Blake matter, and we believe that her conduct had consequences for the response of the FBI and DOJ to Blake's misconduct. The deficit was readily apparent to the OIG in the first few months following Blake's detection, and in our view necessitated, for example, that her supervisors become extensively involved in the provision of notifications to contributors and prosecutors. We believe that a senior OGC staff attorney should have demonstrated the leadership to furnish comprehensive and timely legal support services for the Laboratory.

- The Scope of the Laboratory's Remedial Actions

Our review concluded that the Laboratory's remedial actions were not comprehensive enough in two respects: 1) the scope of the Laboratory's self-generated protocol revisions were too narrowly focused; and 2) the assessment of Blake's work for protocol discrepancies failed to account for her work as a Serologist and RFLP technician, which together accounted for 12 of the 14 years that she was employed in the DNAUI.

As described earlier, after the Laboratory identified Blake's wrongdoing, the DNAUI promptly changed its operating procedures to require the inclusion of GeneScan® data in the case file and its review by two Examiners. Laboratory Deputy Director DiZinno explained that once the Laboratory understood exactly what Blake had done, the necessary changes in procedure occurred quickly. The DNAUI Unit Chief also requested that, as part of the Unit's annual protocol review, his program managers submit recommendations for protocol revisions that took into account Blake's wrongdoing. The only suggestion that was offered, however, was to institute what already had been done by that time: include GeneScan® data in the case file.

We believe that Blake's actions should have triggered an extensive reevaluation within the DNAUI of its protocols. DiZinno told the OIG that one of the lessons learned from the Blake situation is that the Laboratory could not count on the trustworthiness of all of its employees. Within the first two months of learning of Blake's wrongdoing, the Laboratory should have laid the groundwork for a comprehensive reevaluation of the DNAUI's protocols. Instead, the Laboratory seemed to focus on a far narrower issue - how do we spot someone who has developed an aversion to processing negative controls involving amplified DNA samples - and did not comprehensively examine its protocols, which is a clear deficiency.

We further believe that the Laboratory erred when it decided to limit its investigation of Blake to the last two years of her work, pending the discovery of additional incriminating evidence against her. The Laboratory did not even ask Blake's serology and RFLP supervisors whether they had noticed anything suspicious about her work until the OIG asked in October 2003 what assessment the Laboratory had conducted on Blake's work from 1988 through March 2000 concerning the risk that she had violated DNAUI protocols. The DOJ Criminal Division also raised this issue in a letter to the Laboratory at the end of October 2003.

The Laboratory has taken the position that no additional inquiry is warranted on the cases that Blake handled during her 12-year tenure as a serologist and RFLP technician primarily because it appears that Blake's major failing was limited to her aversion to running STR negative controls, there is no indication that she ever intended to manipulate test results, and the procedural controls in place in the DNAUI would have caught any misconduct. We think, however, that the message from the totality of circumstances surrounding Blake, including her 1994 performance appraisal and training history, is not so narrowly tailored: Blake was an untrustworthy employee who manipulated the DNAUI's procedures and lied about her conduct. The Laboratory's confidence in its serology and RFLP protocols to detect misconduct by Blake also must be considered in light of the fact that its STR protocols did not detect her misconduct.72

We have no evidence that Blake, in fact, violated DNAUI protocols while working as a Serologist or RFLP technician. We also have no indication that Blake's supervisors from 1988 to March 2000 failed to scrupulously evaluate her work and catch and correct every discrepancy that appeared in her casework. But we also believe that the Laboratory was not fully aware at the time of the kind of employee it was dealing with. Under these circumstances, a file review of a subset of Blake's early work, where identifiable, is appropriate taking into account what is now known about Blake's conduct.73

- Oversight of Blake's PCR Qualification Testing and Early PCR Work

Although Blake's work and training performance was deficient at times, she did not receive additional scrutiny from the Laboratory, either during her qualifying testing to become a PCR Biologist or as she completed her first few examinations as a PCR Biologist. We believe that this was an error. Blake's record in the DNAUI was inconsistent enough to warrant additional scrutiny. The Examiner who oversaw most of Blake's work as a PCR Biologist was not made aware of her negative performance issues until after she was caught. Also, no one asked him to pay closer attention to Blake's work. Blake's supervisors should have had more information, consistent with applicable law and regulations, and should have been looking more closely for discrepancies in her work. Although it is not possible to say with certainty that Blake's misconduct would have been discovered earlier if her supervisors had had more complete information, we believe that the additional scrutiny would have increased the probability that she would have been detected prior to April 2002. Moreover, if her work had been analyzed during her initial qualifying and proficiency tests as a PCR Biologist, or during her first several tests as a PCR Biologist, her failure to run the negative control tests would likely have been detected by the summer of 2000 before she had processed many cases.

V. RECOMMENDATIONS

With regard to the FBI's response to Blake's misconduct, we recommend the following:

- To facilitate prompt communications with evidence contributors and prosecutors in the event of future testing problems, the Laboratory should maintain the following information in an electronic format that can be shared conveniently with other FBI components (such as, FBI OPR and FBI OGC) and DOJ: all contributor contact and case information currently required for an evidence contributor to request an evidence examination (see FBI Handbook of Forensic Services, (https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/handbook-of-forensic-services-pdf.pdf/view); the e-mail address of the evidence contributor; and the name, title, agency, address, telephone number, and e-mail address of any associated prosecutor(s);

- In circumstances where a protocol violation renders testing results scientifically invalid and a report from the Laboratory is not expected to issue within 180 days from the discovery of the violation, the Laboratory should notify the evidence contributor of the following information within 90 days of learning of the violation: the nature of protocol violation; how the violation occurred; the remedial measures that the Laboratory intends to implement in the case to generate scientifically valid testing results; and the time needed to complete the remedial measures and to issue a final report.

- The FBI Laboratory should perform a file review of a sample of cases that Blake is known to have worked on prior to becoming a PCR Biologist to reconfirm that the procedures that were required in fact are documented as appropriate in the case files.

- Around this time Blake also applied to become a Special Agent, but her application was rejected due to inadequate testing scores. She also withdrew from a lecture course for DNA Examiners because she was receiving failing marks.

- RFLP is a technique that detects variation in a DNA sequence according to differences in the length of DNA fragments. These fragments are created using enzymes that cut the DNA strands at specific points. RFLP is a more restrictive technology than PCR/STR. It requires greater amounts of higher quality DNA to generate a profile, and takes considerably more time to complete. RFLP also is not as sensitive to contamination.

- According to one of Blake's Examiners, however, the instructor indicated to him during the training that Blake was performing satisfactorily and meeting the requirements of the training program.

- The statement "No Size Data" is the message that the Genotyper® software displays when no DNA is detected in a sample (i.e., there is "no size data" because there were no DNA peaks for which Genotyper® could assign a size).

- That section provides in pertinent part: "All technicians will typically document their involvement in the analytical processing of physical evidence by initialing the lower left corner of each page of the work product in which they were involved in generating."

- As explained supra, while Blake's misconduct prevents the Laboratory from stating definitively that contamination did not distort her testing results, to date, reexamination of Blake's analyses, including retesting of evidence samples, has confirmed the accuracy of her work. As of February 2004, evidence in 27 of 90 cases where Blake failed to process the negative controls had been retested.

- DNA is not available for retesting for two of these profiles.

- In 2003, the FSSU was renamed the CODIS Unit.

- According to the FBI, as of March 2004 the Laboratory was waiting for the resubmission of evidence in 13 out of the 29 cases for which NDIS profiles previously were removed. Reanalysis has been completed in an additional four cases, and currently is being completed in one case.

- In United States v. Smith, Criminal No. 2000-399(JCL) (D.N.J.), a civil rights action against five Orange, New Jersey, police officers for the death of a prisoner in their custody, the defense moved for a new trial after the Government disclosed that DNA test results that were admitted into evidence by stipulation had been generated by Blake without proper processing of the negative controls. After extensive submissions and argument, the court ultimately denied the defendants' motion, concluding that the introduction of the suspect evidence did not undermine confidence in the result of the trial. According to the DOJ Criminal Division, in the cases in which evidence that Blake handled was introduced, no defendant has successfully persuaded a court that Blake's protocol violation mandated a reversal of the conviction.

Challenges to exclude DNA evidence that was tested using STR technology also have been made in the Superior Court of the District of Columbia on grounds that the FBI's DNA protocols and quality assurance standards are neither minimally reliable nor generally accepted in the scientific community, and that Blake's conduct exemplifies the unreliability of the testing procedures. See United States v. Orlando Roberts, Crim. No. F-771-01, and United States v. David Veney, Crim. No. F-3986-00. The court in these cases denied the defendants' motions to exclude DNA evidence on these grounds. Blake did not analyze the DNA evidence in either case.

- See, e.g., "More Wrongdoing Found at FBI Crime Lab," Guardian Unlimited, April 16, 2003; "New Misconduct at FBI Lab Threatens Cases - Worker Lied at Trial; Other Accused of Shoddy Testing," The Baltimore Sun, April 16, 2003; see also "Voodoo Science and Another FBI Scandal," The Sunday Herald, April 20, 2003.

- Memorandum from FBI Laboratory, Scientific Analysis Section to FBI Director's Office, April 30, 2002 at p. 2.

- Adams has since become the Assistant Director of the Laboratory Division (hereafter "Laboratory Director").

- In October 2003, the OIG asked the FBI what assessment the Laboratory had conducted of the risk that Blake had also committed misconduct while employed in the DNAUI as a Serologist and RFLP technician. The Laboratory replied that it was not prepared to offer a response at the time and thereafter interviewed Blake's former supervisors about her early work in the DNAUI. The same month the DOJ Criminal Division wrote to the Laboratory Director and recommended that the FBI "formulate a strategy to determine if Jacqueline Blake violated any protocols in her previous work assignments in the FBI laboratory," and that "[t]he FBI should work with the Criminal Division to design a plan for a preliminary inquiry . . . ." The Laboratory responded by letter dated January 28, 2004, that its risk assessment was completed and that it "is not aware of any outstanding technical issues that would potentially compromise the testing results previously generated by Ms. Blake in the areas of serology and RFLP analysis." The Laboratory reached this conclusion based on the facts that: 1) the analysis of her STR casework had not identified any "procedural departure[s]" other than her failure to process the negative controls; 2) the methodologies used in serology and RFLP work do not involve the use of amplified products from negative control samples; 3) any irregular control performance would have been detected through the quality assurance program and promptly addressed; and 4) the Laboratory's quality assurance controls, including proficiency testing programs and the direct supervision of Examiners, were in place when Blake was performing her serology and RFLP work. In short, the FBI Laboratory has expressed that it does not believe that an examination of Blake's work from August 1988 to March 2000 is warranted because Blake's primary failing was her aversion to processing STR negative controls - something that was not part of her serology and RFLP duties - and it is confident that its quality assurance controls would have caught her if she engaged in misconduct.

- The NDIS match was generated from a convicted offender sample. The underlying criminal case involved an investigation of extortion, and the evidence tested was a letter. The FBI Laboratory, through the local FBI field office, requested a blood sample from the incarcerated offender to verify the match. After Blake's misconduct was discovered, the Laboratory also requested the return of the original evidence sample for retesting. The Laboratory never received the requested blood sample and the evidence was not returned for retesting. Follow-up contact by the Laboratory subsequently disclosed that prosecution was declined in the underlying criminal action. In another matter, the DNAUI generated a match in NDIS between one of Blake's profiles and an incarcerated offender. After Blake's misconduct was discovered, the profile was removed from NDIS and retesting performed. The newly generated profile matched the DNA profile of the same offender that previously was identified by NDIS. In addition, the Laboratory identified matches in a local DNA database from two of Blake's profiles. In one case, the FBI obtained resubmitted evidence and issued a new report. The profile from the retested evidence matched a profile in NDIS. The FBI is still waiting to receive evidence in the second case despite repeated requests to the contributor to resubmit its evidence.

- Blake processed 105 offender samples. The Laboratory has retested 75 of these samples and expects to complete retesting of the remaining 30 by the end of March 2004. The Convicted Offender Program currently has a backlog of 24,000 samples waiting to be processed.

- The FBI Laboratory has a goal for each unit to process its evidence within 60 days of receipt.

- At the time, the Assistant General Counsel was the primary OGC point of contact for the Laboratory.

- The April 30, 2002, memorandum described the Laboratory's early remedial actions, such as requiring inclusion of GeneScan® data in the casefile, the removal of Blake's profiles from NDIS, and the collection of Blake's STR data files.

- In response to a draft of this report, the DOJ Criminal Division stated that the role of its attorneys in the Blake matter was limited to learning the pertinent facts, identifying legal issues related to criminal prosecutions that required attention, and monitoring to the extent necessary the FBI's response to these prosecution-related legal issues. The Criminal Division further explained that it was never asked to provide programmatic, scientific, or policy advice on issues related to Blake's misconduct. Our review found, however, that the work of the Criminal Division attorneys was not so limited, and the Counterterrorism Section in fact provided recommendations to the FBI on matters not specifically identified with criminal prosecutions. For example, in October 2003 Sabin wrote to the Director of the FBI Laboratory and stated that "[t]he FBI should formulate a strategy to determine if Jacqueline Blake violated any protocols in her previous work assignments in the FBI laboratory. The FBI should work with the Criminal Division to design a plan for a preliminary inquiry, and should keep the Criminal Division advised of any findings." We also were told that the Counterterrorism Section requested the FBI to provide prompt notifications to the evidence contributors who have not yet been told that Blake had processed their evidence improperly. These are cases where the Criminal Division believed that there are no prosecution-related legal issues (e.g., that Blake's work will not be relied upon to gain a conviction). Whether prosecution-related or not, we concluded that the advice of the Counterterrorism attorneys was appropriate.

- FBI personnel have expressed confusion over the work that Sabin was directed to perform. One FBI employee asserted that Sabin did not explain his role, while another employee said that he "did not know how DOJ management fits in." According to the Deputy Director of the FBI Laboratory, no meeting was ever held where the various FBI and DOJ participants identified their roles and responsibilities. Sabin told the OIG that he explained his role (as described in text above) to the OGC and to the Deputy Director of the Laboratory.