On September 23, 2005, agents from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) attempted to arrest long-time fugitive Filiberto Ojeda Ríos (Ojeda) at a residence on a rural hillside near Hormigueros, Puerto Rico. Ojeda was one of the founders and leaders of the Ejército Popular Boricua, also known as the “Macheteros” (Cane-Cutters), an organization that claimed credit for various violent crimes during the late 1970s and 1980s in pursuit of independence for Puerto Rico.

A team of FBI agents attempted to enter the residence to arrest Ojeda at 4:28 p.m. The operation resulted in a brief but intense exchange of gunfire between Ojeda and the FBI. Three agents were shot and one was seriously wounded; Ojeda was not hit. The agents did not enter the house or complete the arrest. The gunfight was followed by a standoff during which Ojeda’s wife surrendered and FBI agents engaged in a dialog with Ojeda. At 6:08 p.m., an FBI agent saw Ojeda through a window and fired three shots at him. Several agents heard Ojeda cry out and fall. The FBI did not enter the house until shortly after noon the next day, at which time the agents found Ojeda on the floor, dead from a single bullet wound that punctured his lung.

Journalists, elected officials, and activists in Puerto Rico criticized the FBI for using excessive force to capture Ojeda, for conducting the operation on El Grito de Lares (a holiday of great significance to the Puerto Rican independence movement), and for waiting 18 hours after Ojeda was shot before entering the house, thereby allowing Ojeda to bleed to death.

On September 26, FBI Director Robert Mueller requested that the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) conduct an investigation to determine the facts and circumstances of the Ojeda shooting incident and to make recommendations regarding what actions, if any, the FBI should take in connection with it. The FBI and the United States Attorney General also received written requests from several United States Representatives and other elected officials for an independent investigation of the circumstances of Ojeda’s death.

The OIG initiated this investigation after receiving Director Mueller’s request. In August 2006, we completed a 172-page report detailing our findings and recommendations. This Executive Summary, which is also being made available in Spanish, summarizes the full report.

II. The Methodology of the OIG Investigation

The OIG’s objective in conducting this review was to investigate the facts relating to the incident, and: (1) to determine whether the FBI agents involved in the operation complied with the Department of Justice’s Deadly Force Policy; (2) to assess the FBI’s decision to conduct an emergency daylight assault of the Ojeda residence in light of other potential options for apprehending Ojeda; (3) to assess the FBI’s planning for and conduct of negotiations with Ojeda during the standoff; (4) to determine the reasons the FBI waited 18 hours after the shooting to enter the residence; and (5) to evaluate communications between the FBI, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and the public regarding the operation. As the investigation proceeded, the OIG identified several additional issues that are addressed in this report, including anonymous allegations that the FBI had bypassed numerous opportunities to arrest Ojeda under circumstances less likely to result in violence.

The OIG investigation was conducted by a team of attorneys and OIG Special Agents. In the course of the investigation, the OIG interviewed over 60 individuals, including personnel from the FBI Counterterrorism Division in Washington, D.C., and agents from the FBI’s Critical Incident Response Group (CIRG) in Quantico, Virginia. These interviews included all of the agents who discharged their weapons or otherwise participated in the assault on Ojeda’s residence, as well as other CIRG agents who planned, participated in, or had knowledge of the operation. We also interviewed personnel from the San Juan Division of the FBI (San Juan FBI) and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Puerto Rico who were involved in the Ojeda matter. OIG investigators interviewed officials from the Department of Justice of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico and the Police of Puerto Rico (POPR). We also spoke with several persons living in the area near the Ojeda residence.

The OIG reviewed thousands of pages of documents generated by the FBI and the U.S. Attorney’s Office relating to the Ojeda matter, including draft and final Operations Plans and Orders, investigative files, court filings, photographs, logs, intelligence reports, text messages, and relevant FBI policies, procedures, and training manuals.

In addition, the OIG reviewed relevant forensic reports prepared by the Instituto de Ciencias Forenses (the Puerto Rico Institute of Forensic Sciences) related to the Ojeda incident. These reports included the autopsy report, bullet and shell casing analyses, trajectory analysis, shooting reconstruction, and blood pattern analysis. We also conducted three lengthy interviews of Dr. Pio R. Rechani López, the Executive Director of the Institute, and other scientists involved in preparing the forensic reports. The OIG acknowledges the cooperation of Puerto Rico Attorney General Roberto J. Sánchez Ramos and Dr. Rechani in making the forensic reports and scientists available to us.

The OIG also consulted with the U.S. Department of Defense Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Office of the Armed Forces Medical Examiner (OAFME), regarding how long Ojeda survived after being shot. The OAFME provided a written report on this issue and responded to questions from the OIG.

In addition, the OIG recruited three experts in tactical police operations to provide expert input and guidance on the FBI’s tactical decisions in the Ojeda operation and the agents’ compliance with the Department of Justice Deadly Force Policy: (1) Ronald M. McCarthy, a former Field Supervisor for the Los Angeles Police Department Tactical Unit who previously served on the U.S. Department of Justice Waco review committee and who has testified before the United States Congress as an expert in police special operations; (2) Michael S. Foreman, the former Chief of the Sheriff’s Office for Orange County, Florida, who has 24 years of experience in the field of special weapons and tactics as a team leader and SWAT commander; and (3) Gary Van Horn, the Assistant Director in the Office of Law Enforcement and Security at the U.S. Department of the Interior, who has over 30 years of law enforcement experience.

During the course of its review, the OIG was unable to interview some witnesses and obtain some potentially relevant written materials. The attorney for Ojeda’s widow declined our request to interview her as well as our request for access to the Ojeda residence. The Department of Justice of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico declined our request for access to statements collected from approximately 40 witnesses, including individuals living in the neighborhood near the Ojeda residence, as well as an expert report prepared for the Commonwealth regarding the survivability of Ojeda’s wound. A Commission of the Puerto Rico Bar Association conducted an investigation of the Ojeda incident, but the Bar Association did not respond to written and telephonic requests from the OIG for information collected in that investigation. We believe, however, that although this information might have been useful to the OIG’s investigation, our findings and conclusions were not materially affected by our inability to obtain access to it.

In this section of the Executive Summary, the OIG summarizes historical information regarding Ojeda and the Macheteros, and then describes the FBI’s planning for the Ojeda arrest operation.

- Historical Background Regarding Ojeda and the Macheteros

- The FBI Locates Ojeda in Hormigueros

- Deployment of the Hostage Rescue Team

- The Surveillance and Arrest Plans

- The Role of the Police of Puerto Rico

Ojeda was born in Puerto Rico in 1933. In the mid-1970s Ojeda helped to organize the Macheteros. The publicly stated goal of the Macheteros is to obtain the independence of Puerto Rico by armed struggle against the United States government. The FBI considers the Macheteros to be a terrorist organization. Ojeda was the leader of and spokesman for the Macheteros.

The Macheteros have claimed responsibility for various acts of violence in Puerto Rico, such as the murder of a police officer in Naguabo, Puerto Rico, in August 1978 and the killing of U.S. Navy sailors in Puerto Rico in 1979 and 1982.

The Macheteros have also claimed responsibility for numerous bombings in Puerto Rico. On October 17, 1979, the Macheteros conducted eight bomb attacks against various federal facilities across Puerto Rico. In January 1981, the organization used bombs to destroy nine U.S. fighter aircraft at the Muñiz Air National Guard Base in Carolina, Puerto Rico. Later the same year, the Macheteros bombed three separate buildings of the Puerto Rico Electric Company. In 1983, the Macheteros fired a Light Anti-Tank Weapon (commonly called a LAW rocket) into the U.S. Federal Building in Hato Rey, Puerto Rico, damaging the offices of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the FBI. In January 1985, the Macheteros fired a LAW rocket into a building in Old San Juan that housed the U.S. Marshals Service and other federal agencies.

The Macheteros also conducted robberies to finance their activities, including the theft of $7.1 million from a Wells Fargo facility in West Hartford, Connecticut on September 12, 1983. The Wells Fargo robbery was one of the largest bank robberies in U.S. history.

On August 30, 1985, the FBI conducted a large-scale operation in Puerto Rico to arrest Ojeda and other alleged members of the Macheteros in connection with the Wells Fargo robbery. According to contemporaneous FBI accounts, Ojeda did not respond to loud announcements from the agents of their presence and intent to execute a warrant at his residence. When the FBI entered Ojeda’s residence, Ojeda fired several shots down a stairway at the arrest team. One of the shots ricocheted and struck an agent, permanently blinding him in one eye. Ojeda fired more shots and threatened to shoot anyone who attempted to climb the stairs. After a dialog with the agents, Ojeda allowed his wife to surrender to the FBI. A few minutes later, Ojeda appeared at the base of the stairs holding a pistol in his left hand and an Uzi shoulder weapon in his right hand. The agents instructed him in Spanish and English to drop his weapons. According to the agents, Ojeda then raised the pistol. One of the agents fired at Ojeda. The shot struck Ojeda’s pistol and knocked it from his hand. Ojeda dropped the Uzi and was subdued by the agents.

Ojeda represented himself in his 1989 trial in Puerto Rico on the charge of assaulting the FBI agents during the arrest operation, arguing self defense. He was acquitted by a jury.

Ojeda was released on bond pending trial in Connecticut on charges relating to the Wells Fargo robbery. On September 23, 1990, Ojeda cut off his electronic monitoring device and announced that he had gone back underground to continue the struggle against the government of the United States. Ojeda thereby violated the conditions of his release and became a federal fugitive. The United States District Court in Connecticut issued an arrest warrant the next day, charging Ojeda with bond default. In July 1992, Ojeda was tried in absentia in Connecticut and found guilty on 14 counts related to the Wells Fargo robbery, fined $600,000, and sentenced to 55 years in prison.

After becoming a fugitive in 1990, Ojeda periodically gave interviews to the media in Puerto Rico, and his recorded speeches were played at pro-independence rallies. According to media accounts and FBI files, in these statements Ojeda reiterated that the Macheteros remained active as an organization and he continued to advocate an “armed struggle” for independence. In 2003, Ojeda issued a letter condemning an FBI “wanted” advertisement that included a photograph of his wife. Ojeda described the Macheteros as “indestructible” and urged supporters to send him the names of FBI agents in Puerto Rico for future publication.

The Ojeda arrest operation was the culmination of a major investigative effort by the San Juan FBI that was led by Special Agent in Charge (SAC) Luis Fraticelli. In early September 2005, the San Juan FBI determined that Ojeda and his wife were likely living in a house located on a rural hillside in Hormigueros, on the west side of Puerto Rico. At this point, the San Juan FBI had not seen Ojeda at the house. The San Juan FBI was concerned that the remote location and rugged terrain would make it difficult to confirm Ojeda’s presence using conventional surveillance techniques.

On September 13, 2005, FBI Headquarters approved a request from SAC Fraticelli for the deployment of the FBI’s Hostage Rescue Team (HRT) to conduct a tactical assessment for the purpose of arresting Ojeda. Based in Quantico, Virginia, the HRT is a full-time, national level tactical team that, among other missions, deploys in support of FBI field division operations. HRT is a component of the Tactical Support Branch in the FBI’s Critical Incident Response Group (CIRG), which also includes the Operations and Training Unit and the Tactical Helicopter Unit. The Operations and Training Unit supports HRT by providing operations management, planning and oversight during HRT deployments. The Tactical Helicopter Unit provides aviation support.

The San Juan FBI sought the assistance of highly specialized HRT “sniper-observers” to conduct covert surveillance to determine whether Ojeda was present and to gather intelligence relevant to an arrest.1 In addition, SAC Fraticelli said he sought HRT’s expertise in conducting the arrest because he was concerned that Ojeda would likely “shoot it out” with the FBI again and that Ojeda might use grenades or explosives.

Agents from the HRT and the Operations and Training Unit prepared plans for a two-phase operation: a surveillance phase followed by an arrest phase. During the surveillance phase, a team of HRT sniper-observers would conduct covert surveillance of the residence, with emphasis on confirming Ojeda’s presence. The sniper-observers would also collect other information relevant to a potential arrest operation, such as identifying the location and composition of “breach points” where the arresting agents could enter the residence.

The plan also called for a Quick Reaction Force to be made up of agents from HRT and the San Juan FBI in vehicles stationed at a location a short drive from Ojeda’s residence. The function of the Quick Reaction Force would be to extract the sniper-observers in the event of compromise and to be prepared for arrest contingencies.

The FBI planners did not make detailed plans for the arrest phase in advance of the operation because they expected that the specific tactics would depend in large part on the results of the surveillance phase. HRT’s preference and primary focus was to make the arrest outside of the residence, such as in a vehicle stop while Ojeda was leaving or approaching the residence.

The FBI plan did not address a scenario in which the FBI would surround the residence and call for Ojeda to surrender, even as a least preferred course of action. SAC Fraticelli told the OIG that he wanted to avoid a standoff or “barricaded subject scenario” because he was concerned that Macheteros sympathizers would assemble near the scene in large numbers and that it would be difficult to control the situation.

In preparing for the operation, the HRT Commander and Deputy Commander decided not to include negotiators from the CIRG Crisis Negotiation Unit (CNU) in Quantico as part of the team. However, SAC Fraticelli made arrangements for two trained negotiators from the San Juan FBI to be available during the operation.

Consistent with FBI crisis management guidelines, the plan for the Ojeda operation provided that SAC Fraticelli was at the top of the Tactical Chain of Command, followed by an Assistant Special Agent in Charge (ASAC) from the San Juan FBI, the HRT Deputy Commander, and the HRT Squad Supervisor.

In planning the arrest operation, the FBI took into account the annual celebration of El Grito de Lares on September 23. San Juan FBI investigators believed that Ojeda might leave his residence and attend the celebration in the city of Lares, thereby presenting an opportunity for a safe arrest away from the residence.

On September 19, HRT set up a Tactical Operations Center (TOC) at a location approximately 25 miles from Ojeda’s residence. In general, the TOC was staffed throughout the operation by the HRT Deputy Commander and other CIRG personnel. The agents in the field communicated with the TOC by radio and cell phone. The San Juan FBI set up a Command Post on a different floor in the same building. In addition, the San Juan FBI Command Post was staffed by SAC Fraticelli, two ASACs, and various agents from the San Juan FBI.

As part of its surveillance plan, the FBI assigned color designations to the four sides of Ojeda’s house in order to facilitate communications. Facing the house, the front side was designated “White,” the left side was designated “Green,” the right side was designated “Red,” and the rear side of the house was designated “Black.”

The POPR was aware that the FBI had been attempting to locate Ojeda, and had provided some assistance to the FBI in this effort. However, the FBI did not give advance notice to the POPR that the FBI had located Ojeda in Hormigueros and was planning to arrest him there. SAC Fraticelli stated that he did not provide advance notice to the POPR because he wanted to keep the operation secret and limit the possibility of leaks. The POPR did not receive notice of the arrest operation until after the FBI began the attempt to arrest Ojeda and the exchange of gunfire, which we describe below, at which time POPR officers responded to the scene and established an outer security perimeter.

IV. Chronology of Events in the Operation

In this section of the Executive Summary, the OIG sets forth a detailed chronology of events in the implementation of the Ojeda surveillance and arrest operation.

- Overnight Events on September 22-23

- Plan for a Pre-dawn Arrest Operation on September 24

- The Compromise of the Sniper-Observers

- The Assault on the Ojeda Residence

- Events Following the Exchange of Gunfire

- Ojeda Struck by a Shot from the Perimeter

- The Decision Not to Enter the House on September 23

- Notification of the Puerto Rico Department of Justice

- Entry of the House on September 24

A team of FBI sniper-observers initiated surveillance of the Ojeda residence before dawn on Thursday, September 22. During daylight hours, the sniper-observers withdrew to a position under cover of vegetation a short distance from the residence.

Later that day, the United States District Court for the District of Puerto Rico issued a search warrant for the residence. The warrant authorized the FBI to execute the search at any hour of the day or night for evidence of violations of several criminal statutes. The original arrest warrant issued in 1990 for Ojeda’s failure to appear at trial for the Wells Fargo robbery remained outstanding.

The sniper-observers resumed surveillance of the residence after dark on September 22. As one of the sniper-observers moved along a fence around the residence, two dogs began barking excitedly. Lights came on inside the residence and at a neighboring residence. The sniper-observer saw a woman on the porch and heard her talking to a man who was in the yard inside the fence, with a flashlight. The man walked close to where the sniper-observer was hiding, but apparently did not see him. The sniper-observer described the man as elderly, with white hair and a medium build, which met the description of Ojeda provided by the San Juan FBI. The sniper-observer stated that he could not see the man’s face clearly, but based on the San Juan FBI description and other information, he concluded the man was Ojeda. This information was relayed back to the TOC at 11:43 p.m. on September 22.

SAC Fraticelli and the HRT Deputy Commander considered whether to order an immediate operation to arrest Ojeda on the morning of September 23. They ultimately concluded that the available information regarding the house was inadequate to assure a successful breach of the front door without killing or injuring the occupants.

The FBI was hopeful that Ojeda would depart the residence by car later that morning to attend the El Grito de Lares celebration, and that he could be apprehended by the Quick Reaction Force at that time. Fraticelli and the HRT Deputy Commander doubled the size of the Quick Reaction Force team on duty between 6:00 a.m. and approximately 10:00 a.m. on September 23, using all available agents from HRT together with SWAT Team agents from the San Juan FBI. In addition, numerous agents from the San Juan FBI were assigned to maintain surveillance coverage at all potential vehicle exit routes near the residence. However, the FBI did not observe Ojeda again that morning.

Based on information about the residence provided by the sniper-observers and advice from the HRT Deputy Commander, Fraticelli decided on a deliberate assault of the residence to arrest Ojeda in the pre-dawn hours of September 24, when Ojeda was expected to be sleeping. At approximately 10:00 a.m. on September 23, all of the HRT agents serving on the Quick Reaction Force returned to their base to rest and prepare for the assault the next morning. Agents from the San Juan FBI SWAT Team assumed Quick Reaction Force responsibilities.

The HRT and Operations and Training Unit agents prepared a plan for the assault. The plan called for the sniper-observers to approach the house late on September 23 to confirm Ojeda’s presence. Early on September 24, the assault units would be delivered by vehicle to a location near the residence, and they would advance toward the house surreptitiously on foot. The assault units would approach the White side of the house, proceed through the front yard, and advance up onto the porch. One group would breach the residence at a door near the Red/White corner, and another group would breach the house at the large window on the Green side. Because the FBI had a “no-knock” search warrant, HRT did not plan to announce itself before breaching. Once inside, the agents would conduct a rapid room-to-room maneuver, called a “clear,” until they captured Ojeda and secured the residence.

At approximately 2:30 p.m. on September 23, the sniper-observers were at their daytime position of cover, in the woods away from the house. One sniper-observer saw a vehicle stop near a trailhead leading toward their position. A second vehicle arrived several minutes later. The sniper-observer heard people talking but could not understand what they said because he does not speak Spanish. Other sniper-observers who were positioned further away from the road also told the OIG that they heard vehicles and voices, but they could not make out what was said. The first sniper-observer moved into position to observe what the speakers were doing, and he saw someone pointing at the ground and toward the trailhead.

The sniper-observers became concerned that the person gesturing toward the trailhead had detected evidence that the sniper-observers had used the trail and their presence had been detected. The sniper-observers’ concern was heightened by the fact that the barking dog incident had occurred the night before and by the belief that the local population included Macheteros sympathizers. The sniper-observers reported these events to the TOC by radio and recommended to the TOC that the Quick Reaction Force “get here ASAP and hit the house.” Several of the sniper-observers told the OIG that their primary concern was that Ojeda would receive warning of their presence and would escape and return underground.

Fraticelli and the HRT Deputy Commander discussed a course of action in response to the reported compromise of the sniper-observers. The accounts of the deliberations differed somewhat between the participants. However, it is undisputed that, based on the recommendation of the HRT Deputy Commander, Fraticelli decided to proceed immediately with the arrest plan that HRT had devised for the pre-dawn hours of September 24. The primary modification of the plan was to transport the arrest team by helicopter to a small banana field in front of the house and have the team “fast rope” to the ground. Fraticelli told the OIG that he was concerned that the FBI would lose the advantage of surprise in this kind of daytime assault by helicopter, but that after consulting with the HRT Deputy Commander he became convinced that an immediate assault on the house was the best option.

Fraticelli made the final “go” decision for the emergency daylight assault at approximately 3:45 or 4:00 p.m. on September 23. Ten HRT assaulters boarded two helicopters. The agents were equipped with helmets, standard issue body armor bearing “FBI” identifiers, and HRT-issued .223 caliber M4 carbine shoulder weapons.

The San Juan FBI SWAT units were at that time stationed in Quick Reaction Force vehicles a few minutes away from the house. The TOC instructed two of the agents to link up with HRT assaulters when they were dropped by helicopter at the banana field and to assist in the assault. The remainder of the Quick Reaction Force was assigned to address any threat posed by any persons at or near a neighboring residence, including those who had been seen or heard near the location of the sniper-observers. Numerous other agents from the San Juan FBI, including two negotiators and an ASAC who was also a negotiator, were summoned to assist at the scene. The HRT sniper-observers moved to various locations around the house and awaited the helicopters.

The HRT helicopters departed for the scene at approximately 4:00 p.m. As the HRT helicopters were approaching the GPS coordinates the pilots had been given for the Ojeda residence, they passed over an open area that ended approximately 1/10 of a mile south of the target coordinates. The pilots could not see the target residence. One pilot sought assistance from the sniper-observers on the radio but did not hear anything. The lead pilot did not want to fly over the target residence, so shortly after passing over the edge of the open area he made a clockwise turn back toward it. The second helicopter made a similar turn. The assaulters completed a rope drop into the open area, which was on a steep slope.

On the ground, the 10 HRT assaulters realized that they were not at the planned banana field landing zone. They moved quickly up a steep hill to a road, where they encountered an agent from the San Juan FBI at a vehicle surveillance point in an SUV. The assaulters got into the SUV or climbed on its running boards and rear bumper, and the agent drove them quickly to the Ojeda residence.

At 4:28 p.m., the SUV carrying the 10 HRT assaulters approached the residence. As the SUV approached, two sniper-observers moved closer to the house, and they were detected by dogs inside the fence, which began barking loudly. Another sniper-observer moved forward to open the closed driveway gate to the residence, but the vehicle crashed through the gate toward the house without stopping. The SUV came to a stop in the front yard, near a low cement wall.

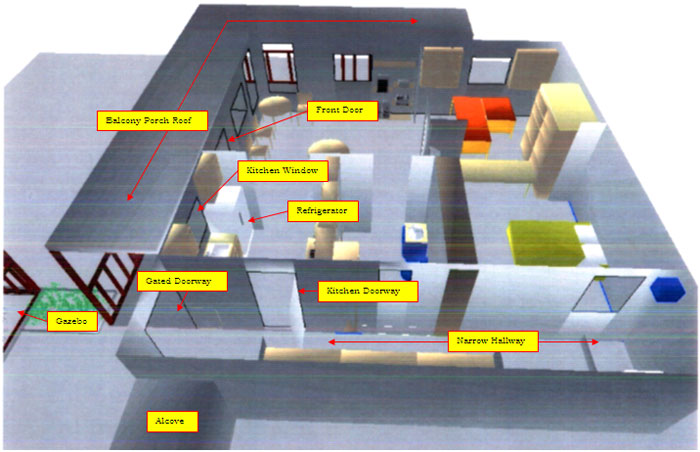

A break in the wall lead to cinder block steps running up a short but steep embankment to an open balcony porch along the White (front) side of the house. The front door was at the top of the steps, and there was another doorway covered by a wooden gate near the Red/White corner of the house. Between the front door and the gated doorway there was a kitchen window with slatted panes.

Figure A shows the front of the house much as the agents would have seen it when they approached, with many features of the residence obscured by vegetation. Figure B is a photograph taken after the foliage was removed, with several important features of the residence labeled. Figure C is a three-dimensional rendering of the interior of the residence, with important features labeled.

When the SUV was approaching the residence, a sniper-observer who was already positioned near the house threw a non-lethal “flash-bang” grenade toward the Green/Black corner of the house as a diversionary tactic. Several HRT assaulters told the OIG that they thought they heard small arms semi-automatic gunfire from the house even before the SUV stopped. Other assaulters told us they perceived small arms fire coming from the kitchen window as they left the SUV and approached the front of the house.2 The agents moved through the gap in the low cement wall up the cinder block steps. A dog that had been frightened by the flash bang came running toward the steps and an agent shot it to prevent an attack.

Several of the agents reached the porch, and two agents moved to a gated doorway into the house near the Red/White corner. (See the “gated doorway” labeled in Figure B.) The remaining assaulters took various positions on the steps and the embankment to each side of them but did not proceed forward because of the gunfire from the house.

As one of the agents began preparing to open the locked wooden gate in front of the doorway near the Red/White corner, he saw that someone had “goose-necked” a pistol from a door on the left interior side of the hallway. (See the “kitchen door” labeled on Figure C.) The agent said he heard several shots and felt impacts on his ballistic vest. He sought cover on the porch beneath the kitchen window and soon realized that he had been wounded in the abdomen. Another agent near the gated doorway also saw a handgun being fired from the kitchen door behind the gate. The agent returned semi-automatic fire into the hallway with his M4 carbine, firing a full magazine of approximately 28 rounds.

FIGURE A

View of the Front of the Residence (Before Foliage Removed)

FIGURE B

Selected Features on Front (White) Side of Residence (Foliage Removed)

FIGURE C

3-D Diagram of Interior of the Residence

While the wounded agent was seeking cover beneath the kitchen window, a gun was fired from inside the kitchen window. One shot struck the wounded agent’s helmet from behind, but did not penetrate it. Another agent was struck twice in the ballistic vest as he moved down the porch to attempt to assist the wounded agent, but the other agent was not wounded. Several HRT agents told the OIG that thy saw or heard a burst of automatic gunfire coming from inside the kitchen window. At some point during the gunfight, an agent located on the embankment below the porch was struck in the battery pack of his helmet, but he was unhurt.

Eight different HRT agents reported that they returned fire at the kitchen window from various positions on the front porch or the embankment below it. Collectively, the agents estimated that they fired approximately 80 rounds at the kitchen window. Several agents told the OIG that near the end of the gunfire exchange they perceived that several shots were fired from inside the house through the front door, making holes in the door and shattering the wood.3

Many of the agents reported that during the exchange of gunfire they perceived that at least two different weapons were being fired from inside the residence, possibly by two different subjects. Several factors were cited as the basis for this belief: 1) several agents reported that they heard both automatic and semi-automatic fire from inside the residence, leading them to believe that two different guns were being fired; 2) agents reported that early in the exchange shots were fired both out the kitchen window and out the kitchen door toward the gated doorway, leading some agents to believe that there might be two different subjects; and 3) as noted above, several agents misperceived semi-automatic fire coming through the front door of the residence at a moment simultaneous or nearly simultaneous with the bursts of automatic gunfire coming from the kitchen window.

The exchange of gunfire concluded at 4:30 p.m., about two minutes after it began. One FBI agent was wounded. Ojeda was unhurt and the FBI had not entered the house or made the arrest.

After the firing subsided, the wounded agent was evacuated from the porch and the other agents withdrew off the porch and the embankment to positions offering better cover. The wounded agent was driven to a hospital and later airlifted to San Juan, where he underwent emergency surgery.

At approximately 4:48 p.m., a few minutes after the agent was evacuated from the scene, someone inside the residence yelled in Spanish, “someone is coming out.” The front door of the residence opened and Ojeda’s wife, Elma Beatríz Rosado Barbosa (Rosado) emerged with her hands empty and extended in front of her. An agent placed her face down on the ground and handcuffed her. Rosado refused to speak to the San Juan FBI agents who attempted to question her about conditions inside the house, including how many people and weapons were in the residence, whether there were explosives, and if anyone was injured. She was driven to the Metropolitan Detention center in Guaynabo, and was released the next day without being charged.

After the unsuccessful attempt to talk to Rosado, a San Juan FBI SWAT agent began talking to Ojeda in Spanish. From behind the low cement wall below the residence, the agent yelled for Ojeda to exit the residence with his hands raised. Ojeda asked who everybody was, to which agent responded, “the FBI.” Ojeda responded that the agents were criminals, imperialists, colonialists, and the mafia. The agent repeated that it was the FBI and asked Ojeda whether he was injured. Ojeda stated that he wanted to talk to the press. The agent told Ojeda that the press was not coming. Ojeda refused to tell the agent whether anyone else was in the house and said that he would only talk to a particular reporter, Jesus Dávila.4 The agent told him that Dávila was not coming and again asked Ojeda whether he was injured. Ojeda responded, “I’m here.”

Ojeda continued to refuse to surrender and began speaking in revolutionary slogans that, according to the San Juan SWAT agent, sounded like a rehearsed speech. The agent continued to attempt to communicate with Ojeda, but Ojeda eventually said words to the effect of, “you know what I want, shut up.”

A negotiator from the San Juan FBI arrived at the scene and attempted to open a dialog with Ojeda, but Ojeda repeated his demand for Dávila several times. The negotiator contacted SAC Fraticelli by cell phone to report the conversation. Fraticelli refused the request to bring Dávila, telling the negotiator no one would be brought to the scene because it was too dangerous.

The negotiator did not tell Ojeda of Fraticelli’s decision but continued calling out to Ojeda. At some point, Ojeda responded, “I am not going to negotiate with any of you until you bring the journalist Jesus Dávila. Then we can talk about my surrender.” It is not clear that Ojeda’s use of the word “surrender” ever reached Fraticelli, who told the OIG that he did not recall hearing that Ojeda had discussed surrender. However, Ojeda’s statement was relayed to HRT agents in the TOC.

The San Juan FBI negotiator continued to call out to Ojeda, but Ojeda did not respond further. Based on the TOC log and the agent’s statements, the negotiator’s communications with Ojeda took place between approximately 5:30 and 6:00 p.m.

Reports of the incident at Ojeda’s residence were broadcast on local radio shortly after the exchange of gunfire between Ojeda and the HRT. Citizens, including members of the press, soon gathered on a road near the scene. Agents from the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, as well as officers from POPR, arrived to provide outer perimeter security.

Following the evacuation of the wounded agent at approximately 4:40 p.m., HRT agent Brian moved to a position on a hillside to the right of the residence, behind a retaining wall.5 Figure D is a photograph taken from Brian’s approximate position. From this location Brian was able to keep watch over both locations from which shots had previously been fired at the FBI: the kitchen window and the gated doorway. Brian told the OIG he could see the side of a light-colored refrigerator inside the left half of the kitchen window. The refrigerator took up about half of his field of view inside the window. The other half was in darkness. Brian told the OIG that while in his position on hillside behind the retaining wall, he saw the refrigerator door open and the refrigerator light go on. Brian said he saw an individual crouched down with a gun in his left hand pointing out the window. He could not see the individual’s eyes or tell where he was looking. Brian stated that the individual clearly had the weapon pointed in the direction of Brian and other FBI agents, but he was unsure whether the individual was sighting the gun at anyone in particular. No other agent reported being in a position to see what Brian saw in the window.

Brian told the OIG that at that moment he realized that the individual was armed and that Brian was visible to him. Brian was aware that another agent had been wounded earlier by a shot from inside the house and that Brian himself had been struck (but not wounded) by at least one shot from inside the house during the original gunfight. Brian said he was also aware the individual had previously fired his weapon from the window he was currently positioned at and had shot Brian from that window. Brian stated that he concluded that the individual posed an imminent threat to himself and other agents.

Brian said he took his weapon off the “safe” setting, sighted the weapon where he believed the person’s center mass to be, and fired three rounds in rapid succession in single-fire mode. Brian estimated that about three seconds elapsed between the time he saw the refrigerator light come on and the time he fired his weapon. Brian told the OIG he did not see the refrigerator light after he took the shots and that it was possible that the individual was closing the door of the refrigerator at the time Brian took the shots. The shots were fired at approximately 6:08 p.m.

Several agents told the OIG that immediately after hearing three shots from the perimeter, they heard Ojeda scream “ay, ay, ay” and a noise like someone falling down. One agent stated that he heard a moan after the screams. No witnesses reported hearing any other sounds from Ojeda. Several agents told the OIG that they heard Brian state over the radio that he thought he had hit the subject.

FIGURE D

View of Residence from Approximate Position of Shooter

After the three shots were fired from the perimeter, the FBI began making preparations to enter the Ojeda residence. The agents at the scene wanted to enter the residence immediately. However, SAC Fraticelli and the HRT Deputy Commander moved cautiously because of concern that Ojeda might not have been disabled and the possibility that there was a second gunman inside the house.

At 6:34 p.m., the San Juan FBI contacted the power company to arrange to cut off electricity to the residence, in order to provide a tactical advantage to the HRT agents, who were equipped with night vision goggles.6 At 6:49 p.m. an HRT agent detonated an explosive charge that had been placed on the locked wooden gate at the doorway near the Red/White corner of the residence. HRT agents also detonated flash bangs at other locations to create a diversion. An agent opened the wooden gate. There was no reaction from anyone inside the house. The agents looked into the hallway behind the gate but did not see anyone. They did not enter the house during this “limited breach.”

The events in Puerto Rico were being monitored by the HRT Commander in Quantico, Virginia. The HRT Commander told the OIG that shortly after hearing about the limited breach of the gated doorway, he ordered the HRT Deputy Commander in Puerto Rico not to enter the residence that night. The HRT Deputy Commander did not recall receiving such an order, however.7 Both the Deputy Commander and SAC Fraticelli told the OIG that the FBI continued to make plans for entering the residence that night. By 7:41 p.m., a team of HRT agents at the scene was equipped and ready to enter the residence.

By this time, however, senior officials in the Counterterrorism Division of the FBI in Washington, D.C. had become concerned about how events were unfolding in Puerto Rico. Willie Hulon, the Assistant Director for the Counterterrorism Division, had already received telephone reports from SAC Fraticelli regarding events at the scene. Hulon related these conversations to his superior, Gary Bald, the Executive Assistant Director for the National Security Branch. On the basis of Hulon’s description of Fraticelli’s demeanor during these telephone conversations and SAC Fraticelli’s repeated inquiries regarding the status of his request that FBI Headquarters send another SAC familiar with Puerto Rico to assist in the operation, Bald became concerned that Fraticelli needed assistance in managing the situation. Bald felt his concern was confirmed when he received the impression from Hulon that agents at the scene were acting inconsistently with Hulon’s recommendation that they hold the perimeter. Bald believed that there was confusion regarding who was in command of the scene and that HRT was making decisions independent of Fraticelli. On the basis of these concerns, Bald instructed Hulon sometime shortly before 8:00 p.m. that any entry of the residence would have to be approved by Hulon.

At 8:05 p.m., Hulon called Fraticelli and told him that there would be no entry of the residence without Hulon’s approval. During this call, Fraticelli and the HRT Deputy Commander recommended that a nighttime entry be conducted to take advantage of the darkness. Hulon instructed them to submit a written entry plan to FBI Headquarters for consideration.

A short time after the 8:05 call, Hulon and Bald discussed the comparative merits of entering the house that night or the next day, and they decided the entry should be postponed until the next morning. Therefore, before the agents in Puerto Rico had completed a written plan for a nighttime entry, Hulon told Fraticelli that Headquarters had decided against a nighttime entry and that a new HRT team was being sent from Quantico to conduct the entry the next day. Late in the evening, however, Fraticelli called Hulon’s deputy, John Lewis, to make a final appeal for approval of a nighttime entry. Fraticelli stressed the security concerns created by crowds of Macheteros sympathizers assembled near the scene, and the possibility that Ojeda might still be alive and in need of medical attention. Fraticelli told us that Lewis called back approximately 15 or 20 minutes later and told him that Hulon had rejected the proposal.

At 11:33 p.m., the agents at the scene were told that there would be no entry of the residence that night. Many of the HRT agents at the scene told the OIG that they strongly disagreed with the decision.

During the course of the operation, the FBI provided periodic updates to the United States Attorney’s Office (USAO) for Puerto Rico Between approximately 6:45 p.m. and 7:15 p.m., the Criminal Chief for the USAO contacted Roberto J. Sánchez Ramos, the Attorney General for the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and Pedro G. Goyco Amador, the Chief Prosecuting Attorney for the Commonwealth, to notify them of the shooting and to request that local prosecutors be sent to the scene. Sánchez told the OIG that this was the first notification that the Puerto Rico Department of Justice received from the FBI regarding an operation to apprehend Ojeda. Sánchez and Goyco both told the OIG that they inferred from the USAO’s request that Ojeda was seriously injured or dead. When the local prosecutors arrived at the scene, at approximately 8:36 p.m., the FBI did not permit them to approach the house, and at some point the FBI informed them that there would be no entry that evening.

The relief team of HRT agents from Quantico arrived in Puerto Rico at approximately 5:00 the next morning, September 24. Agents in the TOC drafted a written plan for a daytime entry and faxed it to FBI Headquarters. Hulon and Lewis reviewed the draft and recommended minor changes by telephone. At 9:29 a.m., Hulon called Fraticelli and told him the revised plan was approved.

The daytime entry was not conducted until three hours after the plan was approved. The entry plan called for inserting a POPR dog into the residence to determine the location or activity of any occupants. The POPR dog did not arrive until about 11:54 a.m., and stayed only briefly because the handler received instructions from POPR Superintendent Pedro A. Toledo Dávila not to participate in the operation. Toledo told the OIG that he denied the FBI permission to use POPR’s dog because he understood that the FBI feared there might be explosives in the residence and Toledo did not want to put POPR’s dog handler at risk. Hulon approved Fraticelli’s request for permission to conduct the entry without a dog at 12:22 p.m.

The HRT entry team walked up the road adjacent to the Red side of the residence. At approximately 12:34 p.m., three diversionary flash-bang grenades were thrown as the team climbed over a retaining wall, entered the residence through the breached wooden gate, and then advanced through the kitchen door into the kitchen. The agents discovered Ojeda’s body near the front door, face down with a loaded and cocked Browning Hi-Power 9 mm handgun on the floor nearby. Blood from the body had flowed under the door, forming a single narrow stream down the face of the doorstep and creating a bloodstain on the floor of the exterior balcony porch.

Ojeda was dressed in a camouflaged cap, a sleeveless body armor vest, camouflaged overalls, and black combat boots. An FBI emergency medical technician was unable to get a pulse from the body and observed that rigor mortis had set in. After searching the house for any additional occupants, the entry team reported at 12:37 p.m. that the residence was secure and there appeared to be a single dead subject.

The entry team did not immediately turn Ojeda’s body over because of concern that a grenade could be under Ojeda’s torso or in his left hand, which was under his body and not visible. A winch was attached to Ojeda’s vest and the body was pulled out over the front door step onto the porch. Ojeda’s hand fell free and no explosive device was found. The process of pulling the body out the door caused a substantial amount of accumulated blood to be pushed over the doorstep and increased the amount of blood visible on the face of the doorstep.

The FBI’s bomb technicians turned their attention to two items in the house identified as possible explosive threats. A case with protruding wires was removed and opened using the winch. It contained a trumpet.8 A large rucksack found in the bedroom was inspected visually, and no explosive hazards were observed.

At approximately 2:44 p.m., the San Juan medical examiner pronounced Ojeda dead. The scene was turned over to investigators from the Puerto Rico Institute of Forensic Sciences for processing. These investigators removed Ojeda’s body from the residence at approximately 5:00 p.m. A search of the residence was concluded at 9:30 p.m. According to the Evidence Recovery Log, the FBI seized over 100 items from the residence, including a substantial amount of computer equipment, books, and other documents.

V. Findings of the Puerto Rico Institute of Forensic Sciences

In this section of the Executive Summary, the OIG summarizes the findings of the Puerto Rico Institute of Forensic Sciences relevant to this investigation. The Institute assumed the lead role in processing the scene and conducting the forensic analyses relevant to the Ojeda matter. The Institute’s findings were based entirely on the physical evidence; the Institute was not aware of the contents of the agents’ statements to the OIG.

One reason that the FBI deferred to the Institute for the forensic analysis was to avoid allegations that the FBI had manipulated the scene. Dr. Pio R. Rechani López, Executive Director of the Institute, told the OIG that the Institute found no evidence that the FBI had manipulated or tampered with the scene.

- Bullet and Shell Casing Examinations

The Institute’s report of Findings on the Scene stated that a Browning 9 mm pistol was found on the floor of the residence near Ojeda’s body. The pistol was loaded to capacity, with 13 unfired bullets inside its magazine and one in the chamber, indicating that it had been re-loaded. The pistol hammer was found cocked. The pistol had been modified to fire in both automatic and semi-automatic mode. Also found at the scene were 107 spent shell casings from .223 caliber bullets and 19 spent casings from 9 mm bullets.

According to the Autopsy Report, Ojeda died of a single gunshot wound that entered his body just below his right clavicle, perforated the right lung, and exited the middle of his back on the right side. There were no other wounds. The bullet was recovered from inside the “flak jacket” vest Ojeda was wearing.

The autopsy report did not specify a time of death. Dr. Francisco Cortés, the Forensic Pathologist who performed the autopsy, told the OIG that based on the size of the wound and reasonable assumptions about Ojeda’s heart rate and blood pressure, he estimated that Ojeda expired from loss of blood approximately 15 to 30 minutes after being shot. He opined that Ojeda could have survived the wound if he had received immediate first aid and surgical care. Dr. Cortés noted that he does not treat live patients, so that his views on the survivability of Ojeda’s wounds and his estimate of the length of time that Ojeda might have survived were based on his experience as a pathologist and on his review of the medical literature.

The OIG also consulted with the U.S. Department of Defense Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Office of the Armed Forces Medical Examiner (OAFME), regarding how long Ojeda survived after being shot. Based on its review of the autopsy records and other pertinent materials, the OAFME concluded that the wound from the bullet was not immediately fatal, but that it was not possible to determine exactly how long Ojeda would have survived. When the OIG inquired whether Ojeda could have survived longer than two hours, the Medical Examiner responded that it was unlikely.

The Institute conducted microscopic comparisons of bullets and bullet fragments recovered from the scene with bullets fired from Ojeda’s pistol and from the carbines discharged by the HRT agents during the operation. The Institute determined that the .223 caliber bullet recovered from inside Ojeda’s vest was fired from an M4 carbine that the FBI had provided for comparison testing. According to the HRT, this was the carbine used by Brian. The Institute determined that the 9 mm bullets recovered from the abdomen and helmet of the wounded agent were fired from Ojeda’s Browning pistol.

Based on distinctive marks left on the casings by the various weapons’ firing pins, the Institute was able to match all 107 of the .223 shell casings found at the scene to particular HRT weapons. The Institute provided sketches indicating the location where the .223 casings were found at the scene. With one exception, the OIG did not find any significant discrepancies between this forensic evidence and the statements of the agents to the OIG regarding the rounds they fired. The Institute determined that two rounds were fired from a weapon that the OIG determined was assigned to an HRT agent who did not initially report firing any rounds during the gunfight. Neither of these rounds struck Ojeda. When we sought to inquire about these rounds, the agent declined to provide a voluntary follow-up statement to the OIG.

The Institute determined that all 19 shell casings found inside the residence were from 9 mm bullets fired from Ojeda’s pistol.

The Institute estimated the bullet trajectories for many of the 111 bullet holes and 76 bullet impacts found in the residence. The OIG found that the location of the holes and impacts as reflected in Institute sketches and crime scene photographs, together with the Institute’s trajectory analysis, were consistent with the FBI agents’ statements in many important respects. Most significantly, the Institute’s analysis identified the trajectories of the three perimeter shots fired by agent Brian, including the shot that struck Ojeda. The forensic evidence also confirmed that Ojeda fired shots from two locations: from the narrow hallway toward the gated doorway, and from the kitchen window. The trajectory evidence was also consistent with the agents’ descriptions of their locations during the gunfight, including the statements of three agents who reported firing into the kitchen window from positions on the balcony porch and other agents who reported that they fired from positions on the embankment below.

The OIG found only one set of trajectory estimates by the Forensic Institute that conflicted with the statements provided by the FBI agents. Several agents reported perceiving shots from inside the house coming through the front door. No agents reported firing shots at the door. The Institute found, however, that there were three holes in the front door from rounds fired from a location outside the door and from below (from down the cinder block steps), not from inside the house. The Institute also found three impacts in the living room ceiling that corresponded to the holes in the door and confirmed the upward trajectory. We sought voluntary follow-up interviews from several agents who we believe might have fired these shots, but they declined our request. Consequently, we have been unable to determine which agent or agents fired these three rounds through the front door.

The Institute concluded that the bullet that struck Ojeda was one of three shots that originated from a location near the retaining wall at the right side of the house at a distance of approximately 19 feet. The Institute found that the three bullets passed through the kitchen window, penetrated the left side of the refrigerator, and exited the front of the refrigerator. Two of the shots presented impacts or final penetrations within the residence, while the third (the round that struck Ojeda) did not. The third trajectory exited the refrigerator at a height of 49 inches, which the Institute found to coincide with the position of the bullet wound on Ojeda’s body, assuming a crouched position.

The Institute found that Ojeda’s flak vest prevented an immediate spatter of blood at the location where Ojeda was wounded. The Institute concluded that Ojeda took one or two steps toward the front door before falling to the floor, with his head near the door. Two large pools of blood formed, one near Ojeda’s head coming from the wound near his shoulder, and the other near the bottom of his vest further away from the door.

The blood pattern report concluded that the front door was closed at the time the blood was flowing, but that the slope of the floor and the pattern of blood were consistent with slow movement toward the door, forming a stream on the doorstep. Institute personnel told the OIG that the bloodstain on the doorstep was greatly increased when Ojeda’s body was turned over and pulled out the front door onto the porch in order to check for explosive devices. The much larger and more obvious stain appeared in photographs published in some local newspaper reports on Ojeda’s death.

VI. Compliance with the Deadly Force Policy

In this Section, the OIG summarizes its analysis of whether the shots fired by the FBI agents during the Ojeda operation were in compliance with the Department of Justice Deadly Force Policy. The Deadly Force Policy states that a Department of Justice law enforcement officer may use deadly force

only when necessary, that is, when the officer has a reasonable belief that the subject of such force poses an imminent danger of death or serious physical injury to the officer or to another person.... If feasible and to do so would not increase the danger to the officer or others, a verbal warning to submit to the authority of the officer shall be given prior to the use of deadly force.

The FBI’s Manual of Investigative and Operational Guidelines (MIOG) sets forth a definition of the meaning of “imminent danger”:

“Imminent” does not mean “immediate” or “instantaneous,” but that an action is pending. Thus, a subject may pose an imminent danger even if he is not at that very moment pointing a weapon at the Agent. For example, imminent danger may exist if Agents have a probable cause to believe... [t]he subject possesses a weapon, or is attempting to gain access to a weapon, under circumstances indicating an intention to use it against Agents or others....

The FBI’s Instructional Outline for the Deadly Force Policy states that the Policy “shall not be construed to require Agents to assume unreasonable risks to themselves,” and that “[a]llowance must be made for the fact that Agents are often forced to make split-second decisions in circumstances that are tense, uncertain, and rapidly evolving.”

The FBI’s MIOG also contains related policies regarding “fire discipline” which require that all use of firepower be preceded by the acquisition of a known hostile target.

The OIG divided its review of the agents’ use of deadly force during the Ojeda operation into two parts: an assessment of the agents’ conduct during the initial intense exchange of gunfire between 4:28 and 4:30 p.m., and an assessment of Agent Brian’s conduct in firing three rounds from the perimeter at approximately 6:08 p.m., including the shot that struck Ojeda.

- Assessment of the Initial Exchange of Gunfire

- Assessment of the Perimeter Shots

Ojeda fired 19 rounds during the initial gunfight, 8 of which struck FBI agents. One agent was wounded seriously in the abdomen. FBI agents fired approximately 104 rounds during the initial gunfight, none of which struck Ojeda.

Based on our review of the evidence, we concluded that Ojeda opened fire on the FBI agents as they attempted to enter the residence, before any agents discharged their weapons. We based this conclusion on several factors, including the statements of numerous agents at the scene. In addition, because of the elevated position of the residence’s doors and windows, the heavy vegetation obscuring them, and the fact that the interior of the house was darkened, the agents would have had no clear target before Ojeda opened fire. In contrast, Ojeda’s position afforded him a much clearer view of the agents as they approached in the daylight.

Ojeda’s widow, Rosado, declined the OIG’s request for an interview but alleged in statements to the media that the FBI fired first. We believe, however, that Rosado may have interpreted the explosion of a “flash-bang” grenade outside the house as gunfire initiated by the FBI. As previously discussed, an FBI agent detonated the grenade near the Green/Black corner of house as a diversionary tactic as the arresting agents approached, before any gunfire began.9

We concluded that once Ojeda began firing, he clearly posed an imminent threat to the agents. Providing a verbal warning to Ojeda at that point was not feasible. Once the agents realized they were under fire, they were justified in applying deadly force to address the threat, without pausing to warn Ojeda.

Ojeda fired at the agents from two positions: from the kitchen door toward the gated doorway, which the agents were attempting to open, and from the kitchen window at agents on or below the porch. We found that the vast majority of the 104 rounds fired by the FBI during the initial gunfight were fired at these two targets, and that these shots were consistent with the Department of Justice Deadly Force Policy. The Instructional Outline for the Deadly Force Policy states that “[w]hen the circumstances justify the use of deadly force, Agents should continue its application until the imminent danger is ended....” The fact that the agents fired over 100 shots without hitting Ojeda reflected Ojeda’s superior position of cover and elevation, and did not necessarily reflect inadequate fire discipline.

On the basis of forensic evidence, however, the OIG found that the FBI fired three shots through the front door of the residence that may have violated the Deadly Force Policy. None of these shots struck Ojeda or his wife. Nothing in the available witness statements or the forensic evidence suggested that these three shots addressed an imminent threat posed by a person located directly behind the door. However, the agents who we believe may have fired these shots declined to provide voluntary follow-up interviews to the OIG.

The OIG also assessed the three shots that Agent Brian fired into the kitchen window at approximately 6:08 p.m. (the “perimeter shots”). One of these shots struck Ojeda and resulted in his death. We concluded that these shots did not violate the Deadly Force Policy.

Brian told the OIG that he saw an individual in the kitchen window, illuminated by the interior light of the refrigerator. Brian stated that the individual was crouched down with a gun in his left hand pointing out the window. Brian said he sighted his carbine where he believed Ojeda’s center mass to be, and fired three rounds in rapid succession in single fire mode.

We found that the forensic evidence reported by the Puerto Rico Institute for Forensic Sciences was consistent with Brian’s description of where he was and what he saw. Ojeda’s pistol was found on the floor at his side, loaded and cocked, confirming that Ojeda was holding the gun at the moment he was wounded. His wound was also consistent with a crouching position, with his shoulders generally squared toward Brian. Although Brian’s view of Ojeda was partially obscured by the refrigerator at the moment of impact, the forensic evidence indicates that the left side of Ojeda’s body, including his left hand (which Brian said was holding the gun), could have been visible to Brian at or immediately prior to the moment that Brian fired the shots. Based on the trajectory of the three perimeter shots, we believe that at the moment of impact Ojeda may have been moving to his right, behind the refrigerator, possibly because he realized he had revealed himself in the refrigerator light.

In reaching our conclusion about the use of deadly force, we took into account the fact that Ojeda had already fired several rounds out the kitchen window, and had evidenced an intention to kill or injure the FBI agents attempting to arrest him. He had already shot three different agents. In addition, Brian and other agents covering the house were in exposed positions.

The discussions between Ojeda and the FBI during the standoff did not mitigate the threat that Ojeda presented at the moment Brian fired. Ojeda had refused the FBI’s instructions to come out of the house. He appeared at the kitchen window with a gun. Even if Brian had understood Ojeda’s offer to discuss surrender if a reporter were brought to the scene, Ojeda could have resumed firing at the FBI agents at any instant.

For all of these reasons, the OIG concluded that at the moment Brian fired these three shots, he had a reasonable belief that Ojeda posed an imminent danger of death or serious injury to Brian or to other agents, and he therefore did not violate the DOJ Deadly Force Policy. The OIG’s expert consultants agreed with this assessment.

VII. Assessment of the Decision to Conduct an Emergency Daylight Assault

In this Section, the OIG summarizes its assessment of the decision by SAC Fraticelli, in consultation with the HRT Deputy Commander, to order an emergency daylight assault on the Ojeda residence on the afternoon of September 23.

When the sniper-observers reported their belief that they had been discovered by unidentified persons, Fraticelli had to select among several options for action, taking into account the risk that these persons might alert Ojeda to the presence of the sniper-observers or otherwise assist him in evading or resisting arrest. Fraticelli approved a plan proposed by the HRT Deputy Commander to transport ten HRT agents to the residence in two helicopters and conduct an emergency daylight assault on the residence to arrest Ojeda. We concluded that this plan was dangerous to the agents and not the best alternative available to the FBI. In reaching this conclusion, the OIG relied extensively on the assessments provided by its outside experts.

- Foreseeable Risks from a Daylight Assault

- The Surround and Call-out Option

- The Extract and Withdraw Option

- Modification of the Approach Route

- Conducting the Assault on El Grito de Lares

We found that it was readily foreseeable that Ojeda would be armed and prepared to offer violent resistance to the FBI assault that began at 4:28 p.m. on September 23. Moreover, if Ojeda had been armed with a higher power firearm or with an explosive device such as a grenade (which would have been consistent with the FBI’s prior experience with the Macheteros), several FBI agents likely would have been killed or seriously wounded in the operation.

The HRT Deputy Commander stated that when he proposed the daylight assault he believed the FBI would still have the advantage of surprise and could get into the house without a gunfight. After hearing the Deputy Commander’s advice, Fraticelli ordered the daylight assault. We found, however, that the belief that the FBI could surprise Ojeda with a helicopter assault was unrealistic and inconsistent with the primary justification for ordering the assault: the concern that whoever had detected the sniper-observers would alert Ojeda to the FBI’s presence. The assault team did not arrive at the residence until almost two hours after the sniper-observers reported the compromise, providing ample time for someone to warn Ojeda and for him to prepare resistance. In addition, the FBI should have recognized that a plan for delivering the HRT agents by helicopter into a small field located in plain view of the front of Ojeda’s residence would generate a great deal of noise and take enough time to permit Ojeda to arm himself in anticipation of the FBI’s arrival.

The FBI’s plan for an emergency daylight assault was adapted from a plan being prepared for a surreptitious nighttime assault. It was poorly suited to daylight conditions, without the advantage of surprise. Once Ojeda knew the FBI was coming, he had the advantage of high ground, superior cover, and superior visibility. Moreover, the plan called for the agents to approach the house and pass directly in front of the front door and the kitchen window to reach the breach points, which exposed the agents to close range gunfire.

The FBI Critical Incident Handbook describes an “Emergency Assault Plan” as an “immediate measure designed to regain control or stabilize a rapidly deteriorating crisis situation that poses imminent danger to the lives of innocent people.” We concluded that the reported compromise of the sniper-observers and the resulting possibility that Ojeda would escape did not rise to this level of urgency, particularly in light of the available alternatives.

The HRT Deputy Commander told the OIG that after the sniper-observers reported the compromise, no consideration was given to options other than a direct assault on the residence to arrest Ojeda. In light of the risks associated with this option, we concluded that other alternatives should have been given greater consideration.

Although the OIG is critical of the decision to conduct an emergency daylight assault, it is important to note that we are not suggesting that this decision was the cause of Ojeda’s death. Ojeda was not killed or injured during the assault. Ojeda was shot approximately 100 minutes later when he presented a threat of imminent harm to the agents, not because the FBI had selected the emergency daylight assault option.

In consultation with its experts, the OIG determined that a superior option was available to the FBI for attempting to arrest Ojeda after the reported compromise: (1) establish a perimeter around the residence sufficient to prevent Ojeda from escaping, (2) demand Ojeda’s surrender with a short deadline for responding, and (3) if Ojeda refused to surrender, use chemical agents (such as tear gas and smoke) to force Ojeda from the residence. Ojeda’s positional advantage would have been reduced or neutralized in this scenario. The sniper-observers had already provided relevant information regarding the residence, including the limited number of exit points from the house that would have to be covered. This information was sufficient for the FBI to adopt, or at least consider, this plan.

The reasons given by the FBI for rejecting or not considering this strategy were troubling. It appears that a major consideration in the advice given to SAC Fraticelli was the fact that several days earlier, during the planning phase of the Ojeda operation, Fraticelli had stated a preference to avoid a “barricaded subject scenario” because of the potential for crowds of sympathizers to assemble near the scene. But the reported compromise of the operation and the loss of the advantage of surprise changed the circumstances and the comparative risks associated with each option so significantly that the surround and call-out option should have received serious reconsideration. We believe that the mindset of avoiding a barricade situation caused the FBI to ignore that option when the circumstances changed.

We acknowledge that the surround and call-out option presented risks. If the agents attempting to establish a perimeter could not establish positions of adequate cover, they might be exposed to gunfire from the residence, particularly if the subject was armed with a rifle. The agents also faced uncertainty regarding whether they could establish a safe perimeter in an area believed to be populated with Macheteros sympathizers. (As it happened, the FBI successfully established such a perimeter after the agent was wounded.) If it had been necessary to launch chemicals into the house, some agents might have been exposed to fire during that procedure. However, these risks to agent safety were not as great as the risks from a foreseeable exchange of gunfire with Ojeda firing from a position of cover at agents approaching the house directly, or exposed on the porch, at very short range.

We also are concerned that the FBI gave little or no consideration to the option of extracting the sniper-observers without taking immediate action to arrest or surround Ojeda at the residence. In raising this concern, we are not making a finding that the “extract and withdraw” option should have been selected in this case. However, when a subject is not creating a crisis situation that poses imminent danger to innocent people, and the available options for immediately arresting or containing the subject present major risks to agents or others, FBI incident commanders should at least consider seriously the possibility of withdrawing. In this case, we do not believe this option was given more than cursory consideration.

We also found that the FBI could have modified the assault plan to reduce the risk to the agents associated with daytime conditions and loss of the element of surprise. The assault route that the FBI borrowed from a plan for a surreptitious pre-dawn raid – up the front steps and in front of the door and windows on the front side of the house – maximized the exposure of the agents to close-range fire from inside the house. As the FBI was aware, the Red and Black sides of the house had no doors or windows. An alternative approach to the breach point from the Red/ Black corner of the property would have reduced the exposure of the agents to gunfire from the house.

We found no support for the allegation made in some media reports that the FBI conducted the arrest operation on El Grito de Lares (September 23) for symbolic reasons, such as to intimidate supporters of Puerto Rican independence. The operation took place in September because that was when the FBI found Ojeda’s house. The FBI actually planned to arrest Ojeda early on September 24 the day after the holiday. It conducted the emergency assault on September 23 only because of the reported compromise of the sniper-observers.

VIII. Assessment of the FBI’s Decisions Regarding Entry

In this Section we summarize the OIG’s assessment of the FBI’s decisions regarding the delay in entering the Ojeda house after the perimeter shots were fired at 6:08 p.m. The FBI has been criticized for failing to enter the residence for 18 hours after Ojeda was wounded. We divide this analysis into two parts: decisions made before 8:05 p.m. on September 23 while SAC Fraticelli remained in charge of the operation, and decisions made after 8:05 p.m. when FBI Headquarters assumed approval authority over any plan to enter the house.

- FBI Entry Decisions in Puerto Rico before 8:05 p.m.

- Entry Decisions made at FBI Headquarters

- The decision to require Headquarters approval

- The decision not to enter the residence

We found that between 6:08 p.m. and 8:05 p.m., the FBI in Puerto Rico was following a cautious, methodical approach in preparing to enter the Ojeda residence. The FBI executed a limited breach of the gated doorway at 6:49 p.m. and was preparing to enter and clear the residence after darkness fell and the electricity was cut off. The primary considerations driving this approach were the concern that Ojeda might not be incapacitated and might still present a threat to the agents, and the belief, based on perceptions during the initial gunfight, that there might be a second gunman inside the residence. This approach was designed to exploit HRT’s tactical advantage in the dark. It also provided time to gain intelligence about the situation inside the residence and to ensure the entry team was fully prepared. We concluded that if Fraticelli had retained control of the entry decision, the entry probably would have occurred shortly after 8:09 p.m. when electric power to the residence was cut off.

The available forensic evidence indicates that Ojeda likely expired from blood loss before 8:09 p.m. As a result, even if Fraticelli’s plan had been implemented, Ojeda was likely dead by the time the FBI would have entered the residence.

We concluded that the FBI’s approach was motivated by considerations of agent safety, not by any desire to withhold medical treatment from Ojeda.

One allegation made after Ojeda’s death was that the FBI knew Ojeda was seriously injured because of the appearance of a large bloodstain on the front doorstep and the balcony porch floor. Several Puerto Rico media outlets published images of the bloodstain. However, crime scene photographs show that most of the staining occurred on September 24, when Ojeda’s body was turned over and pulled out the front door to check for explosives. Moreover, the agents at the scene likely would not have been able to see the blood that accumulated before Ojeda’s body was moved, because their view of the doorstep would have been obscured by heavy foliage or by the balcony railing, as shown in Figures A and D. In addition, it is not clear that Ojeda’s blood had yet flowed onto the doorstep before 8:09 p.m., when the power was cut and the porch was in darkness. None of the agents we interviewed reported seeing a bloodstain on September 23.

At 8:05 p.m., Assistant Director Hulon informed SAC Fraticelli that any plan to enter the Ojeda residence would have to be approved in advance by the Counterterrorism Division in FBI Headquarters. When Fraticelli and the HRT Deputy Commander proposed a nighttime entry, Hulon instructed him to submit a written entry plan. Later that evening, before any written plan had been submitted, Hulon and Executive Assistant Director Gary Bald decided that there would be no entry until a team of relief agents from Quantico arrived the next day. We reviewed both the procedural decision to require Headquarters approval of an entry plan and the substantive decision to reject a nighttime entry operation.

Bald made the decision to assume Headquarters control over the entry decision. A significant factor in Bald’s decision was his assessment of Fraticelli’s demeanor and lack of confidence, based on Hulon’s description of conversations with Fraticelli. Bald stated that this assessment was confirmed by what he believed were indications that HRT was acting independently of Fraticelli. The decision to require Headquarters approval for the entry was made in the context of a shared belief among senior Headquarters officials that Headquarters involvement was needed to provide balance and perspective to decision-making at the scene.

It was difficult for the OIG to evaluate Bald’s assessment of Fraticelli’s demeanor and confidence. Hulon told us that Bald’s assessment was fair in light of the description Hulon had given to Bald of Hulon’s conversations with Fraticelli. In particular, Bald was disturbed by Fraticelli’s request for assistance from another SAC and repeated inquiries regarding the status of this request. However, we did not find evidence, based on the decisions made in Puerto Rico between 6:08 p.m. and 8:05 p.m., that Fraticelli was overwhelmed or lacked sufficient confidence to manage the situation. Under Fraticelli’s command, the FBI in Puerto Rico was proceeding cautiously and methodically toward a nighttime entry of the residence after the power was cut off. Moreover, we found that Fraticelli’s explanation of his reason for requesting help from a particular SAC with experience in Puerto Rico in the event of a protracted crisis was objectively reasonable.