The FBI’s White-Collar Crime (WCC) program can be separated into the general areas of financial crimes and integrity in government crimes. Financial crimes include fraud-related crimes such as corporate, health care, and bank fraud. Integrity in government involves issues such as public corruption and government fraud.

In FY 2004, the FBI allocated 2,342 agent positions for all white-collar crime matters throughout its field offices, which accounted for 41 percent of the total resources allotted to program areas within the CID.36 In conjunction with its change in focus to terrorism-related matters, the FBI reduced the number of positions it allocated for white-collar crime by 118 field agent positions (or almost 5 percent) between FYs 2000 and 2004. As shown previously in Exhibit 3 3, this was the least significant reduction within the traditional crime program areas with the exception of Civil Rights.

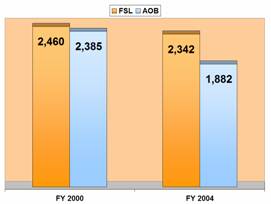

In our analysis of Agent On-Board (AOB) data, we found that the FBI was using approximately 500 fewer agents on white-collar crime matters when comparing utilization data for FY 2004 to data for FY 2000. During FY 2000, the FBI utilized 2,385 agents on these investigations while the number of on-board agents dropped to 1,882 during FY 2004. Exhibit 5 1 compares the allocation of white-collar crime positions to the actual utilization of FBI resources for FYs 2000 and 2004. During each of these FYs, the FBI utilized fewer agents on white-collar crime matters than it allocated. The FY 2004 difference between allocated and actual was six times greater than FY 2000’s variation.

| EXHIBIT 5-1

ALLOCATION AND UTILIZATION OF FBI AGENTS ON WHITE-COLLAR CRIME MATTERS FISCAL YEARS 2000 AND 2004 |

|

| Source: OIG analysis of FBI RMA Office and TURK data |

The FBI also opened 7,992 fewer white-collar crime cases during FY 2004 than in FY 2000. In FY 2000, the FBI opened 19,893 cases, whereas in FY 2004 it opened 11,901 cases.

The FBI is the primary federal investigative agency that investigates financial crimes. No other federal agency has the investigative authority to handle the range of financial-related violations as the FBI. Although other federal agencies are involved in certain areas, such as health care fraud, these agencies are more narrowly focused in their investigations. The FBI has the authority to investigate nearly all violations in the financial arena, including securities, health care, and bank fraud. The FBI’s national financial crime priorities are listed in Exhibit 5-2.

| EXHIBIT 5-2

FBI NATIONAL FINANCIAL CRIME PRIORITIES37 |

|---|

| 1. Securities and Commodities Fraud |

| 2. Health Care Fraud |

| 3. Financial Institution Fraud |

| 4. Money Laundering |

| 5. Insurance Fraud |

| Source: FY 2005 FBI Program Plans |

Overall Changes within the FBI’s Financial Crime Efforts

In the area of financial crimes, the FBI experienced reductions in agent utilization and case openings between FYs 2000 and 2004. In August 2002, the FBI revised its established dollar-related thresholds for addressing financial crime investigations, which has generally limited its investigations to high-dollar matters. We found that these changes have affected other law enforcement agencies in certain jurisdictional areas, especially in the area of financial institution (or bank) fraud, as detailed in the sections that follow.

FBI Agent Utilization and Casework Data

Apart from its overall allotments to white-collar crime, the FBI does not allocate funded agent positions to specific financial crimes except health care fraud, which is discussed later in this chapter. Therefore, we were unable to provide an overview of agent allocation changes to financial crimes. However, we were able to assess the FBI’s actual agent utilization in financial crime matters. Our analyses show that the FBI’s investigative personnel resources for financial crime investigations decreased from 1,641 on board agents in FY 2000 to 1,335 in FY 2004, or an almost 20 percent reduction.

We also identified differences in the utilization of agents on financial crime matters for the seven field offices we visited (presented in Exhibit 5 3). Six of the seven offices used fewer agents on these investigations during FY 2004 than in FY 2000, with the Phoenix Field Office experiencing the greatest reduction of 50 percent.

| EXHIBIT 5-3

FBI AGENT UTILIZATION ON FINANCIAL CRIME MATTERS FOR THE FIELD OFFICES VISITED FISCAL YEARS 2000 AND 2004 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field Office | FY 2000 AOB |

FY 2004 AOB |

Change in Number |

Change in Percent |

| Chicago | 71 | 59 | -12 | -17 |

| Los Angeles | 131 | 103 | -28 | -21% |

| Miami | 70 | 63 | -7 | -10% |

| New Orleans | 28 | 20 | -8 | -29% |

| New York City | 120 | 125 | 5 | 4% |

| Phoenix | 28 | 14 | -14 | -50% |

| San Francisco | 41 | 37 | -4 | -10% |

| Source: OIG analysis of FBI TURK data |

Likewise, the FBI’s casework data showed that the FBI opened 6,939 fewer financial crime cases between FYs 2000 and 2004, decreasing from 17,402 cases to 10,463. Moreover, each of the field offices we visited experienced at least a 24 percent reduction in financial crime case openings. Exhibit 5 4 provides data on the changes occurring at each of these offices.

| EXHIBIT 5-4

FBI FINANCIAL CRIME CASE OPENINGS FOR THE FIELD OFFICES VISITED FISCAL YEARS 2000 AND 2004 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field Office | FY 2000 Case Openings |

FY 2004 Case Openings |

Change in Number |

Change in Percent |

| Chicago | 461 | 209 | -252 | -55% |

| Los Angeles | 425 | 325 | -100 | -24% |

| Miami | 383 | 197 | -186 | -49% |

| New Orleans | 299 | 144 | -155 | -52% |

| New York City | 413 | 315 | -98 | -24% |

| Phoenix | 297 | 100 | -197 | -66% |

| San Francisco | 150 | 94 | -56 | -37% |

| Source: OIG analysis of FBI ACS data |

Impact on FBI Financial Crime Operations

At each site we visited, FBI officials indicated that they place more emphasis on those financial crime areas near the top of the FBI’s national priorities (previously presented in Exhibit 5‑2). As a result, FBI officials at many of these locations said they have reduced investigative efforts in low-dollar financial institution fraud (FIF or bank fraud) matters and low priority areas like telemarketing fraud and other wire/mail fraud. To identify high-level investigations, FBI field offices have implemented dollar-related thresholds to determine whether to open a case. These thresholds and their effect are discussed in further detail in the FIF section of this chapter.

We also observed various levels of FBI involvement in financial crime matters during our site visits. For instance, the FBI Miami Field Office essentially maintained the same number of financial crime squads between FYs 2000 and 2004 with only a slight reduction in agent resources. In contrast, the number of investigative squads focused on financial crime matters in the FBI Phoenix Field Office declined during this same period from five white-collar crime squads in FY 2000 to two in FY 2004, both of which focused almost exclusively on public corruption matters.

Impact on Other Law Enforcement Agencies’ Financial Crime Efforts

In general, the other federal agencies we visited were primarily involved in other crime areas and were not heavily involved in financial crime investigations either before or after the FBI’s reprioritization. Therefore, the FBI’s reduced efforts in financial crimes have not affected their operations. However, USAO representatives and USAO case management data indicated that the FBI’s reprioritization has resulted in fewer financial-related matters being referred for U.S. Attorney review and prosecution. Additionally, several state and local law enforcement agency officials commented that their departments and communities were negatively affected by the FBI’s decreased efforts in certain financial crime areas.

Other Federal Law Enforcement Agencies

Of all the federal agency officials we interviewed, only USAO officials commented on the FBI’s reduced financial crime investigative efforts and the resulting reduction in criminal matters being referred to the USAO for review and prosecution. According to USAO case management data, actual FBI financial crime matters referred to the USAOs declined from 6,794 to 4,193 between FYs 2000 and 2004, a reduction of almost 40 percent.

In certain instances, the USAO representatives commented that they attempted to encourage other federal agencies, such as the U.S. Postal Inspection Service or Internal Revenue Service (IRS), to increase their investigative efforts in financial crime matters. Generally, the USAO officials we interviewed considered non-FBI agencies to be able to conduct most financial crime investigations. However, these officials noted that the FBI remains the premier investigative agency for financial-related matters. These officials said they did not believe another agency was as capable as the FBI on highly complex cases or capable of completely backfilling any investigative gap resulting from the FBI’s reduced financial crime efforts.

In addition, officials at six USAOs commented on the experience level of FBI agents who are still handling traditional crime matters, including financial crime cases. Some of these officials said the FBI took experienced agents from the white-collar crime area and moved them to counterterrorism squads. According to these prosecutors, the sophistication of financial crime cases requires significant experience to effectively address case needs. With fewer experienced agents left to handle these complex investigations, these prosecutors commented that the quality of FBI financial crime cases has been affected.

State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies

Several of the state and local law enforcement agency representatives that we interviewed indicated that their operations related to financial crime matters were negatively affected by the FBI’s changed priorities. They commented that since the FBI’s shift in priorities there has been less FBI involvement on their cases, primarily because the cases did not meet the FBI’s investigative threshold. In many locations, the officials specifically noted that FIF investigations were impaired the most. Many remarked that their agencies did not have sufficient resources or expertise to effectively handle these matters by themselves. As a result, they believed many FIF crimes were unaddressed.

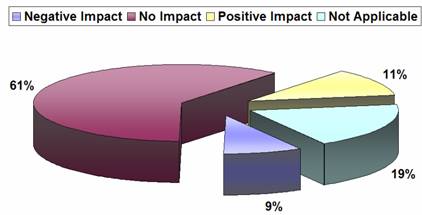

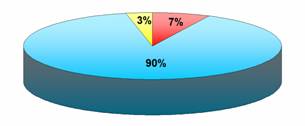

According to our survey of state and local law enforcement officials, the majority responded that their white-collar crime investigations were not affected by the FBI’s new priorities, while 106 out of 1,231 respondents (or 9 percent) indicated a negative impact on their investigative efforts in this area. Exhibit 5-5 presents these survey results.

| EXHIBIT 5-5

SURVEY RESULTS OF THE IMPACT ON STATE AND LOCAL LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCIES’ WHITE-COLLAR CRIME INVESTIGATIONS |

|---|

|

| Source: OIG analysis of survey responses |

The following sections of this chapter provide more detailed analysis of the FBI’s investigative changes by specific financial crime areas. Specifically, we discuss FIF, telemarketing and wire fraud, health care fraud, and corporate fraud. Additionally, we provide comments obtained from non-FBI law enforcement officials related to each area, including any perceived impact on their law enforcement operations.

Financial Institution Fraud (Bank Fraud)

A variety of criminal acts can be categorized as FIF, including bank failures, check fraud, and loan fraud. [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED]

In general, FBI officials at each field office we visited stated that their offices had de-emphasized low-dollar FIF investigations and essentially left them for other law enforcement agencies to handle. While none of the offices had completely stopped investigating these matters, all reported that they limited their efforts to the most significant cases.

Statistical Analyses

We analyzed FBI agent utilization and casework data to assess the level of FBI investigations involving FIF matters. Specifically, we determined the changes occurring within the FBI overall and at the field office level between FYs 2000 and 2004. Additionally, we reviewed the FBI data according to the dollar losses involved on these investigations, in particular FIF matters under $100,000 and those greater than or equal to $100,000. We performed similar analyses of USAO case management data to identify, from the USAOs’ perspective, the changes resulting from the FBI’s reduced emphasis on FIF matters.

FBI’s Overall FIF Efforts – Our analyses of FBI data support FBI officials’ reports of decreased investigative efforts on FIF matters. During FY 2000, 499 agents worked on FIF cases. This number dropped to 337 during FY 2004 – a decrease of 162 agents, or 32 percent. Similarly, the FBI opened 5,011 fewer FIF cases in FY 2004 than in FY 2000 – decreasing from 10,383 cases in FY 2000 to 5,372 in FY 2004.

USAO case management data demonstrates that the FBI was the primary federal law enforcement agency investigating FIF matters in both FYs 2000 and 2004. In FY 2000, the FBI contributed 81 percent of all FIF matters referred to the USAOs. Although this proportion dropped to 67 percent in FY 2004, the FBI remained the predominant agency providing FIF matters to the USAOs. Between FYs 2000 and 2004, the USAOs received a total of 1,701 fewer FIF matters from federal agencies. The FBI essentially accounted for all of this decrease, reducing its FIF referrals by 1,700.

The 7 FBI field divisions we visited reduced the number of FIF referrals to their respective USAOs, with 6 divisions decreasing referral numbers at least 40 percent. The FBI New York City Division was an anomaly, decreasing its FIF referrals by only 4 percent. The following exhibit provides the total number of FIF referrals to USAOs. This table also shows overall FBI referral numbers, as well as referral figures for those field divisions in which we conducted fieldwork.

| EXHIBIT 5-6

FINANCIAL INSTITUTION FRAUD MATTERS RECEIVED BY THE USAOs FISCAL YEARS 2000 AND 2004 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY 2000 | FY 2004 | Number Change | Percentage Change | |||

| All Federal Agencies | 4,000 | 2,299 | -1,701 | -43% | ||

| FBI Field Office Jurisdictions38: | ||||||

| All Divisions | 3,243 | 1,543 | -1,700 | -52% | ||

| Chicago | 143 | 44 | -99 | -69% | ||

| Los Angeles | 72 | 43 | -29 | -40% | ||

| Miami | 52 | 19 | -33 | -63% | ||

| New Orleans | 103 | 24 | -79 | -77% | ||

| New York City | 104 | 100 | -4 | -4% | ||

| Phoenix | 13 | 2 | -11 | -85% | ||

| San Francisco | 34 | 20 | -14 | -41% | ||

| Source: OIG analysis of USA central case management system data |

As our analysis of USAO data illustrates, other federal investigative agencies did not replace the FBI’s reduced efforts in FIF matters.

FBI’s FIF Efforts Relative to Dollar Loss – From our review of individual FIF classifications, we found that FBI agents spent nominal time investigating FIF matters involving losses under $100,000 during FY 2004, [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED]. FBI agents were primarily utilized on FIF investigations involving losses greater than or equal to $100,000. The following exhibit provides a proportional perspective of FBI agent utilization on FIF matters for FYs 2000 and 2004.

| EXHIBIT 5-7

FBI FIELD AGENT UTILIZATION ON FINANCIAL INSTITUTION FRAUD MATTERS FISCAL YEARS 2000 AND 200439 |

|

|---|---|

| FY 2000 | FY 2004 |

|

|

| Source: OIG analysis of FBI TURK data | |

We further analyzed FIF matters associated with dollar-related losses of less than $100,000 and those with losses greater than or equal to $100,000. The FBI experienced overall agent utilization reductions in both areas, but at a much greater level for the lower-dollar investigations. For FIF matters under $100,000, the FBI used over 80 percent fewer agents in FY 2004 than it had in FY 2000, decreasing from 111 on board agents to 20. In contrast, the agent utilization decline on FIF matters with losses greater than or equal to $100,000 was not as substantial. During FYs 2000 and 2004, the FBI utilized 287 and 243 agents, respectively, or a reduction of 44 agents (15 percent).

Of the field offices we visited, the FBI’s data shows that each office used fewer agents on FIF investigations under $100,000. Almost all offices had reduced their efforts on these cases to less than one AOB agent. We also noted that several offices experienced significant decreases in on-board agents for FIF investigations greater than or equal to $100,000. Two offices (New Orleans and New York City) slightly increased the number of agents involved on these cases during our review period. Exhibit 5 8 details the agent utilization changes that occurred between FYs 2000 and 2004 at the FBI field offices we visited, as well as the FBI’s overall agent utilization changes on such matters.

EXHIBIT 5-8

FBI FIELD AGENT UTILIZATION ON FINANCIAL INSTITUTION FRAUD MATTERS

FISCAL YEARS 2000 AND 2004

Field Office

UNDER $100,000

$100,000 AND OVER

FY 2000 AOB

FY 2004 AOB

Change in AOB

FY 2000 AOB

FY 2004 AOB

Change in AOB

Chicago

4.0

0.1

-3.9

15.8

15.2

-0.6

Los Angeles

0.7

0.1

-0.6

34.8

17.3

-17.5

Miami

0.7

0.1

-0.6

9.7

7.3

-2.4

New Orleans

4.0

0.7

-3.3

3.2

3.9

0.7

New York City

1.8

0.4

-1.4

23.0

23.5

0.5

Phoenix

1.9

0.1

-1.8

2.0

1.4

-0.6

San Francisco

1.0

0.1

-0.9

6.4

2.1

-4.3

Total of Sites

Visited 14.1

1.6

-12.5

94.9

70.7

-24.2

Total of FBI

Overall 111.2

19.7

-91.5

287.3

243.2

-44.1

| Source: OIG analysis of FBI TURK data |

Evaluation of FBI casework data provided similar results to that of our agent utilization analyses. Each of the FBI sites we visited initiated fewer FIF investigations during FY 2004 than during FY 2000. Exhibit 5 9 lists the changes in the number of case openings occurring within these locations for our review period. As evidenced in that exhibit, all but 1 of the 7 field offices opened fewer than 10 FIF cases under $100,000 in FY 2004.

| EXHIBIT 5-9

FBI CASE OPENINGS OF FINANCIAL INSTITUTION FRAUD MATTERS FISCAL YEARS 2000 AND 2004 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field Office | UNDER $100,000 | $100,000 AND OVER | ||||

| FY 2000 | FY 2004 | Change | FY 2000 | FY 2004 | Change | |

| Chicago | 114 | 1 | -113 | 129 | 46 | -83 |

| Los Angeles | 6 | 2 | -4 | 73 | 55 | -18 |

| Miami | 27 | 2 | -25 | 51 | 16 | -35 |

| New Orleans | 105 | 23 | -82 | 35 | 26 | -9 |

| New York City | 27 | 9 | -18 | 85 | 55 | -30 |

| Phoenix | 167 | 2 | -165 | 23 | 9 | -14 |

| San Francisco | 44 | 5 | -39 | 24 | 12 | -12 |

| Totals | 490 | 44 | -446 | 420 | 219 | -201 |

| Source: OIG analysis of FBI ACS data |

Impact on Law Enforcement Community

During our fieldwork, we obtained comments from non-FBI law enforcement officials regarding the FBI’s reduced FIF efforts.

USAO Perspectives – In our discussions with the USAOs, prosecutors in the various districts had different views about the impact of the FBI’s reduced FIF investigative efforts. For instance, [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED]. Representatives from both these USAOs stated that the FBI was referring fewer FIF cases for prosecution and that no other federal agency had increased the number of FIF matters to compensate for the FBI’s reduced efforts in this area. However, the USAO official in Chicago indicated that his office was interested in receiving matters that are below the FBI’s threshold while the federal prosecutor in San Francisco was satisfied with the FBI investigating only the most egregious violations. These two prosecutors, as well as prosecutors from the Southern District of New York, did not believe that any other law enforcement agency was able to fill the investigative gap resulting from less FBI effort in this area.

State and Local Law Enforcement Perspectives – State and local law enforcement officials at several field office jurisdictions we visited raised concerns about FIF issues. In particular, they stated that the FBI was less available to assist their agencies in addressing these crimes. One local official in South Florida commented that he stopped requesting assistance from the FBI because he was repeatedly turned down. Several other officials also remarked that they were aware of the FBI’s dollar-related thresholds, and many times only approached the FBI when they had a case exceeding those limits.

In the past, these local agencies said they relied on the FBI’s assistance in investigating these crimes. Now, without the FBI’s involvement, these agencies are left to handle bank fraud matters on their own. The local officials said this has caused problems because their agencies do not have sufficient resources or the expertise to effectively investigate these cases. They said that as a result, many of these crimes are unaddressed. In addition, the officials said they believed that FIF crimes could escalate in the coming years.

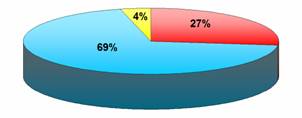

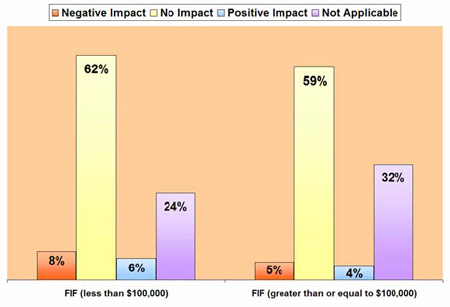

In our survey of state and local law enforcement agencies, we asked participants if the FBI’s shift in priorities had any effect on their investigations of FIF matters with losses greater than or equal to $100,000 and those under $100,000. The majority reported that their investigation of these cases was not affected by the FBI’s reprioritization. However, a few agencies noted an adverse impact on such investigations. Specifically, 101 out of 1,223 responses, or 8 percent, indicated varying degrees of negative impact on FIF matters under $100,000. Exhibit 5 10 illustrates the survey results as related to FIF investigations.

| EXHIBIT 5-10

SURVEY RESULTS RELATED TO THE IMPACT ON STATE AND LOCAL LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCIES’ FINANCIAL INSTITUTION FRAUD INVESTIGATIONS |

|---|

|

| Source: OIG analysis of survey responses |

Conclusions on Financial Institution Fraud Matters

Overall, we determined that FBI field divisions reduced their efforts on FIF investigations, and it does not appear that any other law enforcement agency has fully replaced the FBI’s contributions. Consequently, an investigative gap exists for low-dollar FIF matters. These results were supported by USAO representatives and state and local law enforcement officials, who believed that no other agency has filled the gap and that a portion of FIF crimes are not being investigated.

According to the FBI, telemarketing fraud, which often transcends state and international boundaries, is an escalating crime problem. Nonetheless, in line with its financial crime priorities, since the FBI’s reprioritization it has reduced its efforts in investigating telemarketing and wire fraud.

The operations of some state and local law enforcement agencies have been affected by the FBI’s decreased efforts in telemarketing and wire fraud matters, although to a lesser extent than for FIF. Telemarketing and wire fraud crimes tend to cross multiple jurisdictions, which hinder state and local departments’ investigations. Moreover, FBI officials commented that no other federal investigative agency has the resources available to devote significant time to these investigations. As a result, the FBI officials believed that some of these telemarketing and wire fraud crimes are not being investigated.

Statistical Analyses

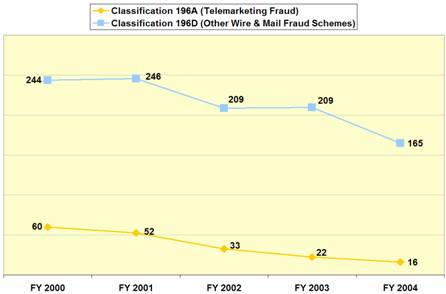

The FBI uses two investigative classifications to track its involvement in telemarketing and wire fraud matters: Classifications 196A (Telemarketing Fraud) and 196D (Other Wire & Mail Fraud Schemes). We analyzed the changes in resource utilization and case openings for each of these classifications between FYs 2000 and 2004. The analyses were conducted for the FBI’s overall efforts, as well as at the field office level. Further, we reviewed USAO case management data to determine the change in FBI referrals to USAO prosecutors.

Overall FBI Efforts – The FBI’s agent utilization data indicates fewer resources were used on Classifications 196A and 196D matters in FY 2004 than in FY 2000. Exhibit 5 11 illustrates the AOB changes that occurred in these two areas during our review period. As shown, 60 agents addressed telemarketing fraud in FY 2000, while only 16 were used in FY 2004. This resulted in a reduction of 44 on board agents, or 74 percent. Similarly, the FBI used almost 80 fewer agents on other wire and mail fraud schemes in FY 2004 than in FY 2000, decreasing from 244 agents in FY 2000 to 165 agents in FY 2004.

| EXHIBIT 5-11

FBI FIELD AGENT UTILIZATION FOR CLASSIFICATIONS 196A (TELEMARKETING FRAUD) AND 196D (OTHER WIRE & MAIL FRAUD SCHEMES) FISCAL YEARS 2000 THROUGH 2004 |

|---|

|

| Source: OIG analysis of FBI TURK data |

Data from the FBI’s ACS system further showed that the FBI reduced its efforts on these investigative matters. Specifically, the FBI opened 159 fewer telemarketing fraud cases during our review period –215 cases in FY 2000 to 56 in FY 2004. Likewise, the FBI initiated 1,727 other wire and mail fraud cases during FY 2000 and 1,062 during FY 2004 – a reduction of 665 cases, or almost 40 percent.

USAO case management data were consistent with the reported FBI reductions in telemarketing fraud investigations. The FBI submitted 18 fewer referrals on telemarketing fraud matters to USAOs during our review period, referring 31 such matters in FY 2000 compared to 13 in FY 2004.

FBI Field Efforts – Based upon FBI data, many of the FBI divisions we visited experienced reductions in terms of agent utilization and casework for both telemarketing and wire fraud classifications during our review period. FBI officials at some of these offices also remarked that they had lessened their efforts in these fraud areas. For example, an FBI official in Phoenix stated that, in response to the FBI’s reprioritization efforts, the office had stopped handling telemarketing fraud cases and disbanded its telemarketing fraud task force. This official said that telemarketing fraud is a significant problem in Arizona, and the U.S. Postal Inspection Service has attempted to increase the number of telemarketing fraud investigations, but there was only so much it could do with its available resources.

Impact on Law Enforcement Community

None of the other federal investigative agencies we interviewed during our site visits were involved in addressing telemarketing fraud or wire fraud. However, we surveyed state and local law enforcement agencies about telemarketing and wire fraud matters. The majority of the respondents (about 60 percent) reported that their operations had not experienced any consequences, good or bad, from the FBI’s reduced efforts in the telemarketing and wire fraud arenas. Our survey revealed that 7 percent of respondents (81 out of 1,224 responses) said they had been negatively affected in these criminal areas, the same percentage who indicated a positive impact on their operations resulting from the FBI’s changes.

Analyses of the survey responses by FBI field office jurisdiction showed that some jurisdictions indicated a greater impact than others. From this analysis, agencies within the Denver, Miami, and Phoenix FBI Field Office jurisdictions experienced the greatest adverse effect related to telemarketing and wire fraud matters, with 12 percent of respondents in each city indicating a negative impact. The following exhibit illustrates the results by field office.

| EXHIBIT 5-12

SURVEY RESULTS OF THE IMPACT ON STATE AND LOCAL LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCIES’ TELEMARKETING AND WIRE FRAUD INVESTIGATIONS ACCORDING TO FBI FIELD OFFICE JURISDICTION | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field Office | Negative Impact |

No Impact |

Positive Impact |

Not Applicable |

| Atlanta | 4% | 56% | 9% | 31% |

| Chicago | 4% | 63% | 5% | 28% |

| Dallas | 3% | 59% | 4% | 34% |

| Denver | 12% | 52% | 7% | 29% |

| Detroit | 9% | 54% | 10% | 27% |

| Los Angeles | 7% | 70% | 3% | 20% |

| Miami | 12% | 64% | 3% | 21% |

| New Orleans | 3% | 56% | 14% | 27% |

| New York City | 6% | 64% | 5% | 25% |

| Phoenix | 12% | 64% | 5% | 19% |

| San Francisco | 11% | 69% | 3% | 17% |

| Source: OIG analysis of survey responses |

Conclusions on Telemarketing and Wire Fraud

Our analyses of FBI data showed that the FBI reduced its investigative efforts on telemarketing and wire fraud matters, using fewer agents to address these matters and opening fewer cases since FY 2000. In addition, some FBI field officials commented that their offices had placed less emphasis on handling these matters than in the past. Based on the data we analyzed and the interviews we conducted, it appears that the FBI’s reduced presence has created an investigative gap in the area of telemarketing and wire fraud because no other section of the federal law enforcement community has significantly increased its efforts in this area.

According to USAO representatives, health care fraud is a significant criminal problem that is expected to increase during the coming years. According to the FBI, several FBI field offices rank health care fraud as their number one white-collar crime problem. In its investigative efforts in this area, the FBI focuses its health care fraud resources on multi-district cases of large health care corporations suspected of committing fraud against government programs and private entities, such as insurance companies, businesses, or individuals. In addition to the FBI, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) OIG conducts many health care fraud investigations, either by itself or jointly with the FBI.

FBI Investigative Efforts

Health care fraud is the FBI’s second highest national priority for financial crime matters. However, our analysis of FBI data showed that fewer agents were addressing these matters in FY 2004 than in FY 2000, and that the FBI opened fewer health care fraud cases during this time period. Additionally, the FBI utilized fewer agents than allocated for health care fraud investigations.

Allocated Agent Positions – Beginning in FY 2003, the FBI allocated field agent positions specifically for health care fraud. Since 1997, the FBI has received funding for its health care fraud efforts through reimbursement from a specialized expenditure account created by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (hereafter referred to as the HIPAA account).40

In FY 2003, the FBI allocated 449 funded agent positions to health care fraud matters. In FY 2004, the total funded staffing level (FSL) had decreased to 420. According to FBI officials, the number of positions allocated to health care fraud is calculated by determining how many agents can be funded by the reimbursement agreement. They said that the number of allocated agents has decreased since FY 2003 because rising salary costs resulted in reimbursement for fewer agents. Prior to FY 2003, the FBI did not specify how many of its white-collar crime FSLs were intended for health care fraud matters; thus, we were unable to compare the change in funded positions between FYs 2000 and 2004.

Actual Agent Utilization – The FBI utilized 418 agents in health care fraud matters during FY 2000. In FY 2004, this number decreased to 377 agents, a reduction of 41 agents.

Moreover, the FBI’s utilization of 377 agents on health care fraud matters in FY 2004 was less than the number of allocated agent positions for such matters. The FBI intended to use 420 field agents in the area of health care fraud, a difference of more than 40 agent positions. As noted previously, we were informed by the FBI that the number of positions allocated to health care fraud is calculated by determining how many agents can be funded by the reimbursement agreement. Therefore, this is a concern because the FBI is utilizing fewer agents on health care fraud matters than allocated to this area and the FBI is being reimbursed by the HIPAA Account for its efforts. The GAO recently issued a report on the FBI’s health care fraud reimbursements and found that the FBI was utilizing fewer agents than budgeted.41 In response, the FBI initiated an extensive manual review to identify other, non-agent salary costs attributable to its health care fraud efforts.42 Further, at our exit conference the FBI provided evidence that it increased its efforts related to health care fraud in FY 2005 compared to FY 2004.

Case Openings – Our analysis of FBI ACS data revealed that the FBI initiated 163 fewer health care fraud cases in FY 2004 than in FY 2000, equating to a 13 percent reduction. During FY 2000, the FBI opened 1,244 health care fraud investigations compared to 1,081 cases during FY 2004.

Field Office Perspectives – Four of the 7 FBI field offices we visited (Chicago, Los Angeles, Miami, and New York City) accounted for almost 30 percent of the FBI’s total FY 2004 agent utilization on health care fraud investigations. Each of these offices also had more agents addressing these matters in FY 2004 than in FY 2000 (as did the San Francisco Field Office). In contrast, the New Orleans and Phoenix Divisions used fewer agents for health care fraud in FY 2004 compared to FY 2000.

According to FBI managers in Miami, South Florida is the epicenter for health care fraud violations. To help combat this problem, the Miami Division has dedicated two squads entirely to health care fraud investigations. However, this FBI official noted that this type of fraud is so problematic in the division’s jurisdiction that the FBI could easily use a third squad to investigate these matters.

To assist in the coordination of health care fraud investigative efforts in Miami, the FBI constructed an off-site facility dedicated solely to health care fraud investigations. The purpose of this facility is to allow FBI agents to work side-by-side on these investigations with personnel from other agencies, such as HHS OIG investigators and federal prosecutors. The facility also serves as a central location for storing health care fraud case files. FBI officials in Miami believed that this facility has enhanced relationships among various agencies and suggested that other large FBI offices, such as New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles, would benefit from establishing similar facilities.

Impact on Law Enforcement Community

As mentioned previously, the HHS OIG is the other federal agency primarily involved in health care fraud investigations.43 Because most health care fraud lies outside the jurisdictional purview of state and local law enforcement agencies, the state and local officials we interviewed did not raise this issue.

We obtained the USAO’s perspective on the FBI’s health care fraud efforts through review of USAO case management data and our interviews with USAO officials. The USAO data reflected reduced FBI efforts related to health care fraud over the past 5 years. However, comments from prosecutors at various USAOs were mixed. While representatives at some USAOs stated that the FBI was not as active in its health care fraud efforts as it was prior to 9/11, prosecutors from other USAOs we visited said the FBI continued its aggressive efforts in combating such violations.

USAO Case Management Data – Analysis of USAO case management data demonstrated that the FBI and the HHS OIG, combined, accounted for approximately 90 percent of health care fraud referrals to the USAOs during FYs 2000 and 2004. In FY 2000, the FBI made 82 percent of such referrals. However, as Exhibit 5-14 shows, the FBI decreased its referrals by 231 between FYs 2000 and 2004. Although the HHS OIG provided 77 more health care fraud matters to the USAOs during this period, the FBI’s 444 referrals accounted for 70 percent of the total health care fraud matters received by USAOs in FY 2004 while HHS OIG referrals accounted for 22 percent of the referred matters. Moreover, total health care fraud referrals declined by 193 matters from FY 2000 to FY 2004, evidencing that despite the HHS OIG’s increased efforts other law enforcement agencies have not fully compensated for the FBI’s reduced investigative efforts in this area.

| EXHIBIT 5-14

HEALTH CARE FRAUD MATTERS RECEIVED BY THE USAOs FISCAL YEARS 2000 AND 2004 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY 2000 | FY 2004 | Number Change |

Percent Change |

|

| Total Referrals | 824 | 631 | -193 | -23% |

| FBI | 675 | 444 | -231 | -34% |

| HHS OIG | 60 | 137 | 77 | 128% |

| Source: OIG analysis of USA central case management system data |

USAO Officials’ Perspective – Prosecutors at some USAO districts mentioned that the FBI’s involvement on health care fraud matters has lessened since 9/11, corroborating USAO case referral decreases shown in Exhibit 5 14. For example, USAO officials in the District of Arizona commented that the FBI’s health care fraud task force was more active prior to 9/11 than it is currently. In addition, USAO representatives from the Southern District of New York stated that they received significantly fewer cases from the FBI in recent months compared to pre-9/11.

Conclusions on Health Care Fraud

Our analyses revealed that the FBI has experienced reductions in both its overall agent utilization and case openings between FYs 2000 and 2004 on health care fraud investigations. Similarly, data from the USAO also showed that the FBI referred fewer health care fraud matters to the USAOs in FY 2004 than in FY 2000.

In addition, fewer FBI agents worked health care fraud matters in FY 2004 than the FBI had intended (underburn). Since the FBI receives congressional funding for its agent positions involved in health care fraud matters, we believe that the FBI must accurately convey the number of agents that will actually be investigating this crime area.

Corporate or securities fraud is the FBI’s top priority within the financial crimes arena. The FBI has placed increased emphasis on this investigative area, primarily a result of the events surrounding the Enron bankruptcy.

Statistical Analyses

Our analysis of the FBI’s agent utilization data confirms the prominence the FBI puts on this crime area. The FBI had 159 agents involved in corporate fraud investigations during FY 2000. In FY 2004, this number rose to 258 agents, an increase of 62 percent.44 In contrast to the increase in resources, the FBI opened 67 fewer corporate fraud cases in FY 2004 than in FY 2000 (524 cases in FY 2000 to 457 cases in FY 2004).

According to USAO data, the FBI submitted the majority of criminal referrals on corporate fraud matters during FYs 2000 and 2004. Specifically, the FBI’s referrals encompassed 74 percent of all submitted corporate fraud matters in FY 2000 and 70 percent in FY 2004. The FBI referred 72 more corporate fraud matters to USAOs during the time period under review, increasing from 303 referrals in FY 2000 to 375 in FY 2004.

Impact on Law Enforcement Community

The nature of corporate fraud does not lend itself to state and local law enforcement involvement. Instead, these violations are generally addressed by federal agencies, most notably the FBI. An official at the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) stated that the SEC’s efforts differ from the FBI’s in this area because the SEC primarily focuses on civil matters, while the FBI investigates criminal violations. This SEC official stated that the FBI has become more selective in the investigations it conducts, focusing on the higher dollar, higher profile cases.

Conclusions on Corporate Fraud

The FBI designated corporate fraud as its top national priority for financial crimes and has increased the number of agents handling those matters between FYs 2000 and 2004. Case management data from the USAO also demonstrated the FBI’s increased emphasis on corporate fraud matters, showing that the FBI had referred more matters to the USAOs during FY 2004 than it had during FY 2000. Further, the other law enforcement entity officials that we interviewed did not indicate that their agencies had been negatively affected by the FBI’s reprioritization in the area of corporate fraud.

The FBI reduced its overall investigative efforts on financial crime matters between FYs 2000 and 2004, resulting in fewer agents handling these investigations and fewer FBI financial crime case openings. Of the specific crime areas discussed in this chapter, we noted reduced FBI efforts (in both agent utilization and case openings) in FIF, telemarketing fraud, wire fraud, and health care fraud. Corporate fraud was the only area in which the FBI used additional agents between FYs 2000 and 2004. Similarly, USAO case management data revealed that the FBI referred fewer criminal matters to USAOs on FIF, telemarketing fraud, and health care fraud matters between FYs 2000 and 2004, while submitting more referrals on corporate fraud matters during this period.

The FBI’s reduced resources on FIF matters had the most noticeable impact on the law enforcement community. In particular, the FBI’s reduced investigative efforts in this area created a gap that other law enforcement agencies have not filled. The FBI generally focused its resources on FIF cases involving large dollar losses, while the low-dollar FIF investigations were seldom initiated. Based upon USAO data, other federal agencies did not replace the FBI’s reduced effort in FIF matters.

To a lesser extent, we determined that a gap exists in telemarketing and wire fraud investigations. These violations often exceed the technical capability and jurisdictional authority of state and local law enforcement agencies.

The FBI’s investigative efforts in health care fraud have also diminished since FY 2000, even though health care fraud is the FBI’s second highest national priority for financial crimes. According to USAO data, the FBI continues to refer the majority of health care fraud matters handled by USAOs. Although USAO case management data indicated the HHS OIG increased the number of its health care referrals to USAOs between FYs 2000 and 2004, the increase only compensated for 33 percent of the FBI’s reduction in such referrals. Thus, it appears that health care fraud is not being addressed as aggressively as in the past.

Finally, corporate fraud is the FBI’s highest investigative priority for financial crime matters. In line with this priority status, the FBI utilized more agents on these investigations and referred more corporate fraud matters to the USAOs in FY 2004 than in FY 2000.

- The FBI does not separately allocate field agent positions between financial crimes and public corruption. Thus, the figures reported within this section of the report include all white-collar crime areas. However, the remainder of this chapter focuses solely on financial crime matters. Chapter 10 discusses integrity in government crimes.

- The priorities established by FBI Headquarters covered the entire White-Collar Crime Program, including both public corruption and financial crimes. This list only presents the financial crime national priorities. However, in relation to all white-collar crime matters, public corruption is the FBI’s top priority. Moreover, the FBI’s national non-priority areas in financial crimes include telemarketing fraud and bankruptcy fraud.

- The FBI’s field office jurisdictions usually coincide with a USAO district; however, in some instances an FBI field office jurisdiction includes more than one USAO district. Following are the FBI field office jurisdictions listed in this exhibit with their corresponding USAOs: FBI Chicago Division – Northern District of Illinois USAO; FBI Los Angeles Division – Central District of California USAO; FBI Miami Division – Southern District of Florida; FBI New Orleans Division – Eastern, Middle, and Western Districts of Louisiana; FBI New York City Division – Eastern and Southern Districts of New York; FBI Phoenix Division – District of Arizona USAO; and FBI San Francisco Division – Northern District of California USAO. The figures presented incorporate the criminal matters submitted to the USAOs within these FBI jurisdictions.

- Other FIF Matters consist of FBI investigative classifications to which a dollar amount is not associated.

- This account is co-administered by the HHS OIG and the Department of Justice. The appropriations are in specified amounts for each fiscal year. Since FY 2003, the FBI’s funding has amounted to $114 million per year. Pub. L. No. 104-191 (1996).

- Government Accountability Office. Federal Bureau of Investigation: Accountability over the HIPAA Funding of Health Care Fraud Investigations Is Inadequate, Report Number GAO-05-388, April 2005.

- The GAO recommended that the FBI establish policies and procedures to report and adequately support the costs of its health care fraud investigations. The FBI agreed with the recommendation and acknowledged the need to establish control mechanisms to monitor both personnel and non-personnel costs.

- The HHS OIG was not one of the federal agencies visited during our audit. Therefore we cannot comment on the impact of the FBI’s reprioritization on the HHS OIG’s operations.

- In FY 2000, the FBI used Classification 196C (Securities/Commodities Fraud) to track its corporate fraud efforts. In FY 2004, it eliminated Classification 196C; instead it used five classifications: (1) 318A (Corporate Fraud), (2) 318B (Prime Bank and High Yield Investment Fraud), (3) 318C (Market Manipulation), (4) 318D (Insider Trading), and (5) 318E (Other Security/Commodities Fraud Matters).