We obtained mixed perspectives from other federal agencies regarding the FBI’s reprioritization from the non-FBI federal law enforcement officials we interviewed. At the headquarters-level, while some agency officials stated that they had not observed significant changes in the FBI’s traditional criminal operations, other agency representatives said they noticed a reduction in FBI investigative effort in traditional crime matters. At the field-level, many non-FBI federal officials we interviewed said they had observed changes in the FBI’s investigative efforts of criminal matters. They commented that the FBI focused much of its attention on terrorism-related matters while pulling back in traditional areas such as drugs and fugitive apprehensions. However, most of these field managers told the OIG they did not believe the FBI’s new focus critically impaired their agencies.

In response to our survey, the majority of the state and local respondents reported a minimal impact as a result of the FBI’s change in priorities. From the survey responses, we selected several local law enforcement agencies to visit during our fieldwork, choosing agencies that indicated varying degrees of impact resulting from the FBI’s reprioritization. Generally, the local law enforcement representatives we interviewed stated that the FBI had reduced its investigative efforts in certain traditional crime areas, which in some instances created an investigative gap.

The following sections provide detailed accounts of the effects that the FBI’s shift in priorities has had on law enforcement agencies at the federal, state, and local levels, including an overview of specific crime areas that were affected by the FBI’s reprioritization.

Federal Law Enforcement Perspectives

Headquarters officials at ATF, ICE, and USMS stated that they had not observed a significant decrease in the FBI’s traditional criminal enforcement operations. However, a DEA Headquarters official stated that the DEA had observed a reduction in the FBI’s narcotics-related work. Despite this reduction in the FBI’s efforts, the DEA official added that the DEA was not adversely affected. U.S. Postal Inspection Service officials commented that the FBI worked more closely with their agency since the reprioritization because the FBI’s resources in this crime area became limited.

By contrast, many field-level officials at other federal law enforcement agencies commented that the FBI was involved less in certain traditional crime matters. However, none of these officials reported negative effects caused by this reduction in FBI involvement. Several of these agency officials said their workload had increased as a result of the FBI’s shift in priorities, but these officials believed their agencies had been able to address the additional investigative matters. However, several officials noted that their agency’s limited resources could potentially hinder their future investigative efforts in traditional crime areas.

Specifically, representatives at six of the eight USMS District Offices we visited commented that their local FBI field offices were handling fewer fugitive investigations, an observation confirmed by FBI resource and caseload data.32 Nevertheless, these USMS field managers asserted that the USMS is fully capable of addressing fugitive matters.

Similarly, managers at six of the seven DEA field divisions we visited commented that the FBI is not as aggressive in working drug-related cases as it was in the past. FBI data supports these observations. DEA field managers did not indicate that their operations were adversely affected by the FBI’s reductions in drug-related work.

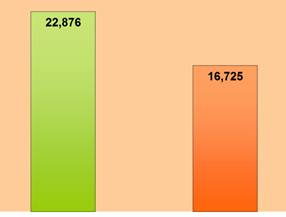

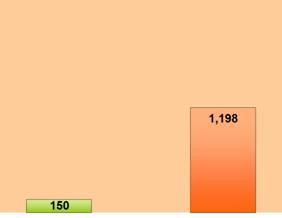

In addition to obtaining comments from federal investigative officials, we gathered feedback from USAO representatives at each of the seven field sites we visited. Officials at all these USAOs noted that the FBI currently focuses its attention on terrorism-related matters, while pulling back in traditional criminal areas such as drugs and bank robberies. USAO Case Management data supports these observations. As shown in Exhibit 4-1, the FBI reduced the number of non-terrorism criminal matters referred to USAOs by 6,151, or 27 percent, between FYs 2000 and 2004, decreasing from 22,876 matters in FY 2000 to 16,725 in FY 2004. Conversely, the FBI referred 1,048 more terrorism-related matters to USAOs in FY 2004 than it did in FY 2000, increasing sevenfold from 150 matters in FY 2000 to 1,198 matters in FY 2004.

| EXHIBIT 4-1 NON-TERRORISM AND TERRORISM MATTERS REPORTED TO USAOs FROM THE FBI FISCAL YEARS 2000 AND 2004 |

|

Non-Terrorism Matters |

Terrorism Matters |

|---|---|

|

|

| Source: OIG analysis of USA central case management system data | |

Officials at five of the seven USAOs remarked that the FBI’s reduced efforts in financial crime investigations have left a significant gap that no other law enforcement agency has filled. These individuals indicated that while other federal agencies handle such cases, they believe these agencies are unable to address the issues to the same extent as the FBI in terms of both the quantity and quality of cases.

USAO officials made similar comments about the FBI’s reduced emphasis on drug-related matters. However, some USAO officials said that the DEA helped fill the gap by submitting additional cases for prosecution. Chapters 5 through 11 contain more extensive information from USAO officials as it relates to particular crime areas.

State and Local Law Enforcement Perspectives

To obtain feedback from state and local law enforcement agencies, we surveyed 3,514 state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies located in the jurisdictional areas of 12 FBI field offices.33 In total, 1,265 agencies responded to our survey, which equated to an overall response rate of 36 percent.34

We judgmentally selected 7 of the 12 FBI field office jurisdictions to conduct fieldwork based on survey responses and analyses of FBI data.35 We spoke with officials at the major police department located in each city visited. In addition, at each site we judgmentally selected local law enforcement agencies to visit. In this selection process, we used responses to the survey, choosing departments that indicated they were either negatively or positively affected by the FBI’s reprioritization. In total, we spoke with officials at 47 departments in these 7 cities. We provide a list of the agencies contacted in each jurisdictional area in Appendix VII.

Survey Analysis

The overall responses to the survey indicated a minimal impact on state and local law enforcement agencies as a result of the FBI’s shift in investigative priorities and resources. The survey contained several questions that asked whether the responding agency’s operations in various investigative areas had been affected by the FBI’s reprioritization. Participants were provided a scaled response to select whether the impact was positive or negative, and the magnitude of such impact. A negative impact was defined as an agency being impaired by the FBI’s shift in priorities, such as if the agency experienced severe difficulty in handling the type of investigation listed. A positive impact was defined as an agency benefiting from the FBI’s reprioritization, such as if the agency significantly enhanced its operations to successfully address the investigative area in question.

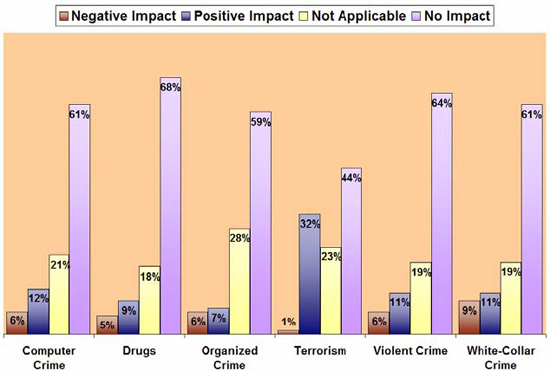

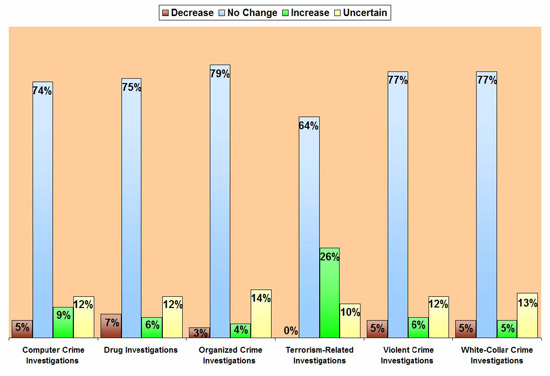

In response, many agencies indicated that their efforts in addressing specific matters were only nominally impacted by any change at the FBI. The following exhibit presents a graphic display of our survey results for general investigative areas of computer crime, drugs, organized crime, terrorism, violent crime, and white-collar crime.

| EXHIBIT 4-2

SURVEY RESULTS OF THE IMPACT ON STATE AND LOCAL LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCIES’ INVESTIGATIONS |

|

| Source: OIG analysis of survey responses |

As shown above, at least 59 percent of respondents indicated that they were not affected by the FBI’s reprioritization in each crime area, with the exception of their investigative efforts on terrorism-related matters. Although several noted no effects in terrorism-related matters, 32 percent indicated that their departments experienced a positive impact from the FBI’s shift in priorities. In turn, no more than 9 percent of survey respondents remarked that they were impaired in any one investigative area. Based on the survey responses, we found that the greatest adverse effect on state and local law enforcement agencies pertained to white-collar crime matters. The chapters that follow contain more in-depth analyses of survey responses related to specific crime areas.

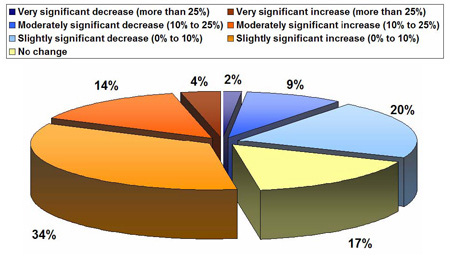

In addition to determining whether state and local agencies were affected by the FBI’s reprioritization, we sought the respondents’ opinion on the FBI’s level of investigative efforts. In particular, we attempted to ascertain if these agencies observed changes in the degree of FBI involvement in addressing certain investigative areas. Exhibit 4‑3 provides a snapshot of these survey results.

| EXHIBIT 4-3

STATE AND LOCAL LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCIES’ OBSERVATIONS OF CHANGES IN FBI INVESTIGATIVE EFFORTS COMPARISON OF CALENDAR YEARS 2000 TO 2004 |

|

| Source: OIG analysis of survey responses |

As depicted in Exhibit 4‑3, the majority (at least 64 percent) noted that they had not observed a change in the FBI’s level of investigative efforts in any one area when comparing calendar years 2000 to 2004. Depending on the investigative category, between 10 and 14 percent of respondents were unaware, or uncertain, of any changes in the FBI’s efforts in traditional crime matters.

The survey also asked questions related to changes in the agencies’ crime rates between calendar years 2000 and 2004 at both an overall level and within individual crime areas. The results showed that 52 percent (581 out of 1,109 responses) experienced an increase, by varying degrees, in their overall crime rate during our review period. In turn, 31 percent noted a decline between calendar years 2000 and 2004, while the remaining 17 percent indicated no change in the crime rate. The following exhibit displays the survey results to the question of overall crime rate changes between calendar years 2000 and 2004.

| EXHIBIT 4-4

STATE AND LOCAL LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCIES’ RESPONSE TO THE CHANGE IN THEIR OVERALL CRIME RATE BETWEEN CALENDAR YEARS 2000 AND 2004 |

|

| Source: OIG analysis of survey responses |

Our survey found that even though the FBI has reduced its investigative effort in traditional crime matters over the last 4 years, state and local law enforcement agencies indicated a minimal impact on their operations resulting from the FBI’s shift in priorities and resources. Additionally, the majority of survey respondents did not observe any change within FBI operations on traditional crime matters.

Discussions with State and Local Officials

As mentioned previously, we interviewed officials at 47 state and local law enforcement agencies within the 7 locations visited. The majority reported that they were aware of the FBI’s new priorities. However, some of these officials were concerned about the FBI shifting its resources away from traditional crime areas to focus them on counterterrorism issues. For example, officials expressed concerns that because they continue to combat traditional (non-terrorism) crimes and the FBI is less available to aide in these local crime-fighting efforts, state and local departments have assumed a greater investigative role, resulting in a greater caseload for their officers and detectives. These officials said that while their departments have done the best they can with available resources, they miss the FBI’s expertise and the quality of its investigative tools. Particular concerns of these local officials are discussed within the following chapters according to specific crime type.

Overview of Affected Crime Areas

Some FBI officials we interviewed stated that the FBI’s more limited presence in violent crime and white-collar crime had impaired the law enforcement community’s efforts to address these crime areas, particularly financial institution fraud and bank robberies. They added that state and local law enforcement agencies generally do not have the necessary resources or jurisdictional authority to effectively address many of these violations, and they commented that no other law enforcement agency has been able to compensate entirely for the FBI’s reduced efforts in these areas.

Our discussions with other federal agencies generally indicated that these agencies were willing and in some cases eager to increase their investigative efforts in those areas in which the FBI has reduced its involvement. However, our review led us to conclude that there are specific criminal areas in which the FBI’s shift of its priorities and resources has affected investigative efforts, as we describe below.

Financial Crimes

Of the types of criminal acts categorized as financial crimes, financial institution fraud (FIF) incurred the most noticeable effect from the FBI’s shift in priorities. From our analyses of FBI data, we found that the FBI was minimally addressing FIF matters under $100,000 in FY 2004 as compared to FY 2000. USAO representatives stated that this lessened involvement by the FBI has created an investigative gap that no other law enforcement agency has sufficiently filled.

To a lesser extent, a gap exists within the law enforcement community related to telemarketing and wire fraud. According to FBI and local law enforcement officials, other law enforcement agencies have not assumed a greater role in these areas due to a lack of resources, technical capability, and jurisdictional authority. Chapter 5 contains more detail on these financial crime matters.

Criminal Enterprises

As noted previously, the FBI’s new Criminal Enterprise Branch oversees all drug, gang, and organized crime investigations. The FBI’s most significant reduction in agent resources occurred in its drug-related investigations, resulting in decreased casework and overall investigative effort in drug crimes. According to DEA field officials, the FBI’s reduced efforts in drug-related crime had not impaired the DEA’s operations in large metropolitan areas. However, the DEA officials raised concerns that smaller urban areas were hurt by the FBI’s shift in emphasis because the DEA often has a limited presence in these areas.

With regard to gang-related investigations, our analyses revealed that the FBI initiated more gang-related investigations during FY 2004 than during FY 2000. Additionally, the FBI did not alter its agent utilization in the investigation of gang-related matters between FYs 2000 and 2004. Nonetheless, certain local law enforcement agencies indicated that they received less investigative assistance from the FBI on gang cases. Further, they commented that the law enforcement community in many metropolitan areas could improve communication and coordination regarding gang-related activity and investigations. A more detailed discussion on gang, drug, and organized crime-related matters is contained in Chapter 6.

Fugitive Apprehension

According to FBI data analysis and interviews with FBI and USMS field managers, the FBI reduced its efforts in fugitive-related investigations since FY 2000. According to USMS field officials, the FBI’s reduced involvement in this area did not significantly impair the operations of other law enforcement agencies. Further details about fugitive matters are contained in Chapter 7.

Bank Robberies

According to the comments of federal, state, and local officials, the FBI is no longer investigating bank robberies at the same level as it has in the past. This was confirmed by our analyses of FBI data. Consequently, most state and local agencies reported that they had experienced an increased bank robbery caseload, which exceeded a few of these agencies’ investigative capabilities. Chapter 8 contains additional information on bank robberies.

Identity Theft

Identity theft was a major concern for the majority of the local law enforcement officials we interviewed, and many said they expect criminal activity in this area to increase in the coming years. They stated that the nature of identity theft investigations is generally beyond the technical capability and jurisdictional authority of state and local law enforcement agencies. Although several federal agencies in addition to the FBI are involved in addressing identity theft, we found no evidence of a coordinated approach for combating this crime. Details on identity theft are conveyed in Chapter 9.

Public Corruption

According to the FBI’s national priorities, public corruption is the FBI’s highest criminal priority. Yet, the FBI’s agent utilization and casework data revealed an overall reduction on public corruption matters. Our review found that some FBI field offices were slow to make changes to emphasize their public corruption investigations over lesser priority areas. However, in FY 2005 the FBI has implemented an initiative to ensure that field offices are appropriately emphasizing public corruption matters, and the FBI has significantly increased its resource utilization in this area in FY 2005 compared to FY 2004. Chapter 10 contains additional details on public corruption matters.

Other Crime Areas

Both FBI and non-FBI law enforcement officials we interviewed cited problems in investigating child pornography, human trafficking, and alien smuggling, particularly insufficient resources to adequately address these crimes. State and local law enforcement agencies, in turn, commented that they lacked sufficient resources and the technical ability and jurisdictional authority that often are required to handle these investigations. In addition, in certain locations we identified a lack of coordination between the FBI and other agencies on these types of cases. Further details about these crime problems are discussed in Chapter 11.

- We spoke with USMS officials from the Eastern District of New York and the Southern District of New York. The FBI New York City Division’s jurisdiction covers these two districts.

- The 12 FBI field offices were Atlanta, Chicago, Dallas, Denver, Detroit, Los Angeles, Miami, New Orleans, New York City, Phoenix, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C.

- The 1,265 agencies responded in varying degrees. Some agencies answered all of the survey questions, others answered all multiple choice survey questions except for the open-ended questions, and others only answered a few questions. Our analyses detailed throughout this report are based solely upon the number of actual responses to each question. Appendix X lists the names of each state and local law enforcement agency that responded to our survey. Some agencies responded more than once, which occurred primarily with the larger-sized police departments. For example, the Chicago Police Department submitted 17 individual responses to the survey, which came from its various bureaus, divisions, and districts. Although not reflected in the figures presented in Exhibit 1‑2, the information provided in these multiple responses from the same agency are reflected in our survey analyses.

- We visited the following cities: Chicago, Los Angeles, Miami, New Orleans, New York City, Phoenix, and San Francisco.