Source: BOP

The Federal Bureau of Prisons' Drug Interdiction Activities

Report Number I-2003-002

January 2003

Inmates' Drug Tests Show Drug Use in Most Institutions

Each year from FY 1997 through FY 2001, more than 2,800 inmates tested positive for drugs.10 Table 2 shows the annual number and rate (or percent) of positive urinalysis drug tests for all BOP institutions. During this 5-year period, the BOP introduced drug detecting technology for use on visitors, increased the number of inmate drugs tests at high security level institutions, and expanded availability of residential drug treatment for inmates. Despite these interdiction activities, the rates of positive drug tests have decreased only slightly over the 5-year period.

Table 2. Number and Rate of Positive Drug Tests for All BOP Institutions

| FY 1997 | FY 1998 | FY 1999 | FY 2000 | FY 2001 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Number of Positive Tests | 2,804 | 2,907 | 3,120 | 3,323 | 3,244 |

| Total Drug Tests Performed | 125,456 | 128,646 | 144,096 | 156,747 | 167,105 |

| Positive Drug Test Rate (%) | 2.24 | 2.26 | 2.17 | 2.12 | 1.94 |

| Source: BOP

Data for each fiscal year excludes institutions that did not have test results for the entire year. Data for two high security level institutions, USP Marion and ADX Florence, which have non-contact visits and little or no inmate movement, were excluded. See Appendix X for a glossary of acronyms. |

Although the BOP's national rate of 1.94 percent in FY 2001 represents all positive inmate drug tests as a percent of all drug tests performed in all BOP institutions, it understates the high level of drug use at some individual institutions. To assess the full picture of inmate drug use, we examined positive drug test rates by institution security levels and rates for institutions within those security levels. Analyzing trends within security levels allows comparison of institutions with similar inmate populations and security features. This analysis shows that despite more enhanced security perimeter features and internal operational procedures at the higher security level institutions, these institutions have a greater level of positive drug tests than other BOP institutions.

Figure 1 shows the rates of positive drug tests by each institution security level for FY 1997 through FY 2001, as compared with the positive drug test rate for all BOP institutions.11

| Figure I. Positive Drug Test Rates by Security Level FY 1997 through FY 2001 is not available electronically |

| Source: BOP

Data for each fiscal year excludes institutions that did not have test results for the entire year. Data for two high security level institutions, USP Marion and ADX Florence, which have non-contact visits and little or no inmate movement, were excluded. See Appendix X for a glossary of acronyms. |

For the administrative, medium, and high security levels, the FY 2001 overall positive drug test rates declined by less than 1 percent from the FY 1997 rates. The minimum and low security levels increased marginally by 0.11 percent and 0.10 percent, respectively. When comparing the FY 2000 and FY 2001 positive drug test rates, rates for all security levels except the low security level decreased, although slightly. At the end of FY 2001, the high security level had the highest overall positive drug test rate, followed by the administrative, medium, low, and minimum security levels. This order of highest to lowest overall positive drug test rate by security level has not changed since FY 1997.

Although the BOP national rate for positive drug tests and overall rates by security level have generally declined, serious drug problems exist at individual institutions. The inmates' urinalysis drug test results show that every administrative, minimum, low, medium, and high security level institution for which data was available had positive tests for use of illegal drugs at some time during the 5-year period from FY 1997 through FY 2001 (see Appendix IV for a complete list of the rates of positive drug tests for individual institutions). Even the high security U.S. Penitentiary (USP) Marion, Illinois, and the Administrative Maximum Security Institution (ADX) Florence, Colorado, which do not allow inmates to have contact visits and have extremely limited and controlled movement of inmates, had positive drug tests at some time during the five years reviewed.

Some institutions have positive drug test rates that are much higher than the national rate and their respective overall security level rate. For example, Table 3 on the next page shows the three institutions for each security level with the highest positive drug test rates for FY 2001.

Table 3. Top Three Institutions With the Highest Rates of

Positive Drug Tests Within Each Security Level for FY 2001

| Institution | FY 2001 Rate (%) |

|---|---|

| BOP National Rate 1.94 | |

| High Security Overall Rate 3.04a | |

| USP Beaumont | 7.84 |

| USP Lompoc | 6.09 |

| USP Leavenworth | 2.65 |

| Medium Security Overall Rate 1.93b | |

| Victorville Medium FCI | 5.52 |

| Tucson FCI | 4.45 |

| Phoenix FCI | 4.10 |

| Low Security Overall Rate 1.44c | |

| Taft CI | 5.94 |

| Beaumont Low FCI | 2.69 |

| Dublin FCI | 2.16 |

| Minimum Security Overall Rate 0.93d | |

| Phoenix FCI Camp | 6.41 |

| Lewisburg USP ICC | 6.40 |

| El Reno FCI Camp | 3.45 |

| Administrative Overall Rate 2.24e | |

| Rochester FMC | 7.61 |

| Springfield USMCFP | 6.27 |

| Los Angeles MDC | 4.19 |

Inmates' Drug Misconduct Charges Indicate Drug Use and Smuggling

Inmates who violate the BOP's rules of conduct receive a misconduct report.12 The prohibited behaviors are divided into four levels of severity: 100, 200, 300, and 400, with the 100-level prohibited behaviors the most serious (see Appendix V for a complete list of the 100-level misconduct charges). The BOP has four drug-related misconduct charges, all of which are 100-level infractions:

During the last three fiscal years, drug misconduct charges within each security level have comprised more than 50 percent of all 100-level misconduct charges. Across all security level institutions, drug misconduct charges have comprised approximately 66 percent of the 100-level charges.13 Table 4 on the next page shows drug misconduct charges as a percentage of 100-level misconduct charges from FY 1999 through FY 2001.14

Table 4. Drug Misconduct Charges as a Percent of 100-

Level Misconduct Charges by Institution Security Level

| Security Level | FY 1999 | FY 2000 | FY 2001 |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | 62.6 | 60.3 | 57.2 |

| Medium | 76.7 | 68.1 | 63.2 |

| Low | 71.7 | 69.0 | 74.1 |

| Minimum | 81.9 | 88.1 | 80.1 |

| Administrative | 72.6 | 65.7 | 56.1 |

| Source: BOP

Data for each fiscal year excludes institutions that did not have misconduct data for the entire year. Data for two high security level institutions, USP Marion and ADX Florence, which have non-contact visits and little or no inmate movement, were excluded. |

For FY 1999 through FY 2001, the BOP's drug misconduct rates show that drugs are smuggled into the institutions regardless of the security level of the institution. We found that all BOP low, medium, and high security level institutions and most minimum security level and administrative institutions had drug misconduct reports issued to inmates at some time during the 3-year period reviewed (see Table 5 on the next page). The total number of misconduct charges for all institutions exceeds 3,500 charges annually and indicates that the BOP's interdiction activities have not been fully successful in preventing drugs from entering its institutions.

Table 5. Number and Rate of Drug Misconduct Charges by Institution Security Level

| FY 1999 | FY 2000 | FY 2001 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Security Level | Average Daily Inmate Population | Total # of Drug Charges | Drug Charge Rates | Average Daily Inmate Population | Total # of Drug Charges | Drug Charge Rates | Average Daily Inmate Population | Total # of Drug Charges | Drug Charge Rates |

| High | 11,895 | 1,356 | 11.40 | 12,380 | 1,336 | 10.79 | 12,750 | 1,154 | 9.05 |

| Medium | 29,716 | 1,400 | 4.71 | 32,038 | 1,437 | 4.49 | 34,986 | 1,358 | 3.88 |

| Low | 36,126 | 565 | 1.56 | 40,308 | 553 | 1.37 | 44,087 | 580 | 1.32 |

| Minimum | 20,969 | 150 | 0.72 | 22,760 | 233 | 1.02 | 22,776 | 179 | 0.79 |

| Administrative | 16,319 | 311 | 1.91 | 17,889 | 322 | 1.80 | 18,973 | 298 | 1.57 |

| Source: BOP

Data for each fiscal year excludes institutions that did not have misconduct data for the entire year. Data for two high security institutions, USP Marion and ADX Florence, which have non-contact visits and little or no inmate movement, were excluded. |

For each security level, Table 6 shows the three institutions with the highest drug misconduct rates for FY 2001.

Table 6. Top Three Institutions with the Highest Rates of Drug

Misconduct Charges Within Each Security Level for FY 2001

| FY 2001 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Institution | Average Daily Inmate Population | Total # of Drug Charges | Drug Charge Rates (%) |

| High Security Overall Misconduct Rate 9.05a | |||

| USP Beaumont | 1,372 | 319 | 23.25 |

| USP Lompoc | 1,509 | 238 | 15.77 |

| USP Leavenworth | 1,679 | 213 | 12.69 |

| Medium Security Overall Misconduct Rate 3.88b | |||

| Phoenix FCI | 1,248 | 142 | 11.38 |

| Victorville Medium FCI | 1,504 | 156 | 10.37 |

| Tucson FCI | 759 | 70 | 9.22 |

| Low Security Overall Misconduct Rate 1.32c | |||

| Taft CI | 1,862 | 172 | 9.24 |

| Forrest City FCI | 1,818 | 61 | 3.36 |

| Beaumont Low FCI | 1,921 | 59 | 3.07 |

| Minimum Security Overall Misconduct Rate 0.79d | |||

| Cumberland FCI Camp Unit | 134 | 6 | 4.48 |

| Leavenworth USP Camp Unit | 333 | 10 | 3.00 |

| Memphis FCI Camp Unit | 306 | 8 | 2.61 |

| Administrative Overall Misconduct Rate 1.57e | |||

| Los Angeles MDC | 818 | 30 | 3.67 |

| Rochester FMC | 789 | 16 | 2.03 |

| San Diego MCC | 772 | 14 | 1.81 |

Other Indicators Show Persistent Drug Use and Smuggling

Data on inmate drug overdoses, drug finds in institutions, and drug cases involving inmates, visitors, or staff are also important indicators of drug problems in BOP institutions. However, this data only partially reflects the extent of the problem because not all overdoses are documented by the BOP and not all drug smuggling is detected.

Overdoses. Between FY 1997 and FY 2001, the BOP reported 18 inmate overdose deaths that resulted from ingested illegal controlled substances. In addition, 32 non-death overdoses occurred from non-prescription drugs or prescription drugs during FY 2000 and FY 200l.15 The BOP was not able to provide us with the number of non-death overdoses that occurred from ingesting illegal controlled substances because its Health Services Division does not track this information.

Drug Finds. The BOP's data on drug finds in its institutions during FY 2000 and FY 2001 shows 1,100 finds, with approximately half of these found on the inmates, in the inmates' belongings, or in the inmates' cells. The data did not indicate how the inmates obtained the drugs or drug paraphernalia. Sixteen drug finds were attributed to visitors and 24 drugs finds were attributed to the mail. For the remainder of the drugs finds, the data showed either they occurred in common areas of the institutions or the locations were not indicated. The sources of entry for the drugs also were not indicated.

Drug Cases. From FY 1997 through FY 2001, the BOP has sustained drug-related misconduct allegations against 93 employees. The cases include introduction of drugs into the institutions, as well as personal drug use.

In addition, from FY 1997 through FY 2001, the FBI opened 791 drug-related cases involving BOP inmates (538 cases), visitors (183 cases), and staff (70 cases) that resulted in 510 convictions or pre-trial diversions. 16,17

OIG data from FY 1997 through FY 2001 shows 34 BOP staff arrests primarily for introduction or attempted introduction of drugs into BOP institutions.

Although the number of drug cases involving BOP staff is less than cases involving inmates and visitors, staff who smuggle drugs can do significant damage to the safety and security of the institutions. At the institutions we visited staff told us repeatedly that while the large majority of staff have high integrity, when staff smuggle drugs into the institutions, the amounts are larger, they reach more inmates, and more money is involved. Several examples of staff arrests in recent years demonstrate the large quantities of drugs staff have introduced or attempted to introduce into BOP institutions.

Cases investigated by the OIG in FY 2002 further illustrate that drug smuggling by BOP staff remains a problem:

Conclusion

The BOP has a continuing problem with inmate drug use and drug smuggling in almost every institution. The indicators of this problem - inmates' positive drug tests, drug misconduct charges, drug overdoses, drug finds, and drug cases - do not show significant progress in the BOP's efforts to prevent drugs from entering the institutions. Based on the continued presence of drugs in BOP institutions, we believe that additional interdiction activities are required.

STOPPING DRUGS AT THE PRIMARY POINTS OF ENTRY

We examined the points of drug entry (see Table 1 on page 2) identified by the BOP and assessed the effectiveness of the BOP's interdiction activities to keep drugs out of its institutions. The BOP staff we interviewed cited visitors as the main source of drugs but were divided as to whether staff or mail constituted the second greatest source.19 Regarding visitors and mail, we concluded that better technology is needed to supplement manual inspections and searches for drugs by correctional officers. We also concluded that more correctional officers are needed to observe inmate activities or assist in searches. We found that the most notable gap in the BOP's interdiction activities is its own staff who are not screened or searched before entering the institutions, and there are no restrictions on the size and content of personal property they can bring into the institutions. Furthermore, BOP staff are not randomly drug tested. These types of interdiction activities are common practices in state correctional systems.

The BOP considers inmate visitors the predominant source of drugs entering its institutions. While the BOP has policies to control visitors' access to the institutions and monitor activities during visits, visitors are still successful in smuggling drugs into the institutions.20 At the institutions we visited, wardens, department heads, intelligence staff, and correctional officers attributed visitors' success in smuggling drugs into institutions to two primary causes: (1) the availability of contact visits, and (2) insufficient cameras, monitors, and staff for monitoring visits.

Contact Visits are a Main Conduit for Drug Smuggling

Visitors hide drugs in clothing, on their person (including body cavities), in baby diapers, and in a variety of other places. Although visitors are required to walk through a metal detector and there are restrictions on personal property permitted into the visiting room, visitors are not pat searched at any institution. Metal detectors do not detect the presence of drugs and ion spectrometry technology, which detects the presence of microscopic traces of illegal drugs on persons, clothing, and other objects, is not available in all institutions. Therefore, contact visits enable visitors to exchange drugs with an inmate by discreetly handing over the drugs, placing them in a food package or beverage purchased from visiting room vending machines, or exchanging the drugs by mouth when kissing.

The BOP considers visitors an important part of an inmate's rehabilitation and encourages visits by family, friends, and community groups.21 Therefore, all inmates receive contact visits, including those housed in disciplinary and administrative segregation units.22 The exceptions are inmates charged or found guilty of misconduct relating to visiting procedures or otherwise placed on visiting restriction by the Disciplinary Hearing Officer. With contact visits, no physical barriers exist between inmates and their visitors, unlike the image portrayed on television where inmates are separated from their visitors by glass and speak through telephones. In the visiting room, inmates sit next to or across from their visitors and are allowed limited physical contact, such as handshaking, embracing, and kissing, at the beginning and end of the visit.

On a busy visiting day, an institution's visiting room can be filled to capacity, with some institutions receiving up to 150 visitors at one time. Many diversions are created by the commotion and activity that occur, such as small children playing, visitors walking back and forth to the vending machines, bathrooms, and correctional officer's desk, and inmates walking to and from the bathroom. These diversions make it difficult for correctional officers to fully supervise each inmate visit and prevent passage of contraband.

Many of the institutions' intelligence staff and correctional officers we interviewed believed, at a minimum, contact visits should be replaced by non-contact visits for inmates housed in high security level institutions because these institutions had the highest rates of positive inmate drug tests and drug misconduct charges. The BOP has demonstrated the success of non-contact visits as an effective drug interdiction technique in high security level institutions. Both USP Marion, Illinois, and ADX Florence, Colorado, prohibit contact visits and both institutions have fewer positive inmate drug tests and drug misconduct charges.

The institutions' intelligence staff and correctional officers also suggested that all inmates placed in disciplinary segregation for drug misconduct charges should be prohibited from contact visits for the duration of their sentence or, at a minimum, for an extended period of time.

Correctional officers and intelligence officers stated that an additional measure to stop drugs smuggled by visitors would be to remove vending machines from the visiting rooms. They also suggested that ion spectrometry technology (or other drug detection technology) should be used to screen visitors before they enter institutions.

Vending Machines Aid Drug Smuggling. Most correctional officers with visiting room experience recommended that the BOP remove vending machines from the visiting rooms because the exchange of food between the visitors and inmates allows for drug smuggling. Each visiting room has multiple vending machines containing candy, ice cream, drinks, sandwiches, and other items, for the purpose of enabling the visitors, who may travel long distances and stay for many hours, and inmates to share food together.

The correctional officers also told us that some visitors buy items from a grocery store identical to items in the institution's vending machines, place drugs in the package, then smuggle the food package into the institution. The visitor buys the identical item from the institution's vending machine, covertly switches the smuggled item with the vending machine item, and gives the inmate the smuggled item with the drugs inside. Such an incident, referred to as the "burrito caper," occurred at one BOP institution. In that incident, a female visitor purchased a packaged burrito identical to ones offered in the institution's visiting room vending machine. She placed heroin-filled balloons inside the burrito and smuggled it into the visiting room.23 She purchased a burrito from the vending machine but switched it with the burrito she had smuggled and gave the drug-laden burrito to the inmate, who ingested the burrito and the drugs.24 The warden at this institution responded to these schemes by removing certain items from the institution's vending machines.

New Ion Spectrometry Technology Lacks Funding. Ion spectrometry technology is designed to detect the presence of microscopic traces of illegal drugs on persons and their clothing.25 The use of ion spectrometry technology to randomly scan visitors for drugs as they enter the BOP's institutions began as a pilot program in 1998 in 28 BOP institutions, funded by a $1.8 million grant from the Office of National Drug Control Policy. The BOP's pilot program tested the technology on visitors to determine the effect on inmate drug use. The BOP concluded that the visitor drug testing program was a significant factor in the decrease of drug use by inmates in medium, low, and administrative institutions, but not in the high security institutions.26 However, BOP could not determine specifically how much the ion spectrometry technology contributed to the decrease in drug use in relation to the BOP's other drug interdiction activities. Approximately 40 BOP institutions currently have the ion spectrometry technology.

At the institutions we visited with ion spectrometry technology, the majority of wardens and correctional officers involved in processing visitors and visiting room monitoring believed ion spectrometry technology is an effective deterrent to drug introduction. However, the cost of the machine is high ($30,000) and the maintenance contract and supplies are also expensive ($3,000-$8,000 per year). During the pilot program, which ended in September 2001, grant funds paid for all purchase and maintenance costs. Now, institutions must fund the machines from their existing budgets. Those institutions that did not receive the technology during the pilot program are uncertain that they can afford to purchase it, and some questioned whether the technology merits the cost when compared to the institutions' other funding needs.

The BOP does not have a strategy to expand the number of ion spectrometry machines. However, the BOP Director told the OIG that the current ion spectrometry machines would be rotated among institutions. When machines are rotated, visitors cannot readily predict institutions' screening tactics, and other institutions that cannot afford to purchase machines could receive a loaned machine to use as part of visitor screening for a period of time.

Insufficient Cameras, Monitors, and Staff for Monitoring

To detect drugs being passed to inmates during contact visits, BOP institutions need a sufficient number of cameras in all areas of the visiting room, a sufficient number of monitors to view the activities the cameras are recording, and a sufficient number of staff to observe the monitors and roam the visiting room for drug detection.27

In several institutions we visited, we observed and correctional officers told us they did not have enough cameras, monitors, and staff to thoroughly observe inmate visiting. For example:

In addition to blind spots and lack of cameras and camera monitoring, correctional officers at several institutions stated that not enough officers were available to roam the visiting rooms on busy visiting days. Some institutions used adjacent "overflow" rooms on these high-volume days, but did not always assign an additional officer to help roam and observe visiting activities.

Conclusion

The BOP officials we interviewed believed that visitors are the main source of drugs entering institutions. The BOP attempts to control the introduction of drugs by limiting visitor access and property, using available technology, providing direct observation of visits in progress, and searching inmates before and after visits. These procedures are important security precautions, but based on the incidences of positive inmate drug tests and drug misconduct charges, enhancements to the BOP's interdiction activities for visitors are needed.

While we believe the vast majority of BOP staff have high integrity, each year the FBI and OIG investigate numerous cases of staff smuggling drugs into the institutions.28 In addition, intelligence officers at the institutions we visited told us the large amounts of drugs found in the institutions are too great to come through the visiting rooms and inmate mail and the most likely source is BOP staff. In fact, the BOP has stated in legal documents that "employees have substantially greater opportunity to smuggle drugs than do the visitors," because inmates and visitors are searched, but staff are not.29 Yet, despite continued cases of staff smuggling drugs, the BOP does not restrict the size or content of personal property staff bring into the institution, does not perform routine searches of staff or their property, and does not randomly drug test staff.30

The BOP's current drug interdiction activities directed at staff consist of background investigations, annual integrity training, and selective drug testing.31 When asked why additional measures are not directed at potential staff drug smuggling, the officials we interviewed at the BOP's Central Office stated that additional staff drug interdiction activities would erode morale. However, at each of the institutions visited, the majority of staff we interviewed at all levels - management officials, correctional officers, intelligence officers, and unit management staff - stated that additional interdiction activities are needed to reduce the institutions' drug problems.32

Property is Unrestricted

The BOP has no policy specifically addressing staff personal property permitted inside institutions. Most institution staff noted the size and amount of personal property brought into the institution by staff has increased over the years. Correctional officers, many employed by the BOP for over a decade, stated that in the past employees generally brought in only their lunch bags. Today, employees bring in any item in any size container. One manager stated, "They bring in backpacks larger than my grandson." Unrestricted property presents a security problem to the institution. Supervisory and management staff told us correctional officers need only wear their uniforms when reporting for duty - anything else the officers need to perform their duties is issued to them by the institution. At each institution visited, we observed staff bringing in duffle bags, backpacks, briefcases, satchels, and large and small coolers.

Institution managers and intelligence staff expressed serious doubt about the effectiveness of eliminating drugs from institutions when they have no control over the property staff bring inside. Several wardens at institutions we visited said they wanted to set guidelines for limiting employee personal property, but believed without a national BOP policy local guidelines would be ineffective due to union opposition. Union officials we interviewed, however, stated they do not oppose placing restrictions on personal property that staff can bring into an institution. (A summary of the union's views is on page 28.)

Restrictions on employee personal property are common in state correctional systems. For example, in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, Adult Prisons Division, employees entering the state prisons are allowed only to possess items issued by the institution to perform their duties or items that their supervisor has permitted. The Pennsylvania State Department of Corrections provides lockers outside the secure perimeters of institutions for correctional officers to store their personal property. Similarly, the Connecticut Department of Corrections restricts the amount and type of personal property staff can bring into the institutions and provides lockers.

Searches are Rarely Conducted

BOP institution staff told us that property restrictions alone on BOP staff would not stop smuggling. If staff wanted to bring in drugs, they could hide the drugs under their clothing when they come into the institutions. They stated that property restrictions in combination with searches of staff and their property would deter drug smuggling.

The BOP Program Statement 5510.09, Searching and Detaining or Arresting Persons Other Than Inmates, allows for searches of staff for reasonable suspicion. However, BOP intelligence officers told us these searches rarely occur. Wardens and intelligence officers stated that unless they have irrefutable evidence an employee possesses drugs, they fear charges of harassment or discrimination for searching staff.33

Many state correctional systems routinely search staff and their property. A 1992 report by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) states that staff in approximately 50 percent of state correctional institutions were patted down when reporting to work.34 For example, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, Adult Prisons Division, searches all hand-carried personal property possessed by staff prior to their entering the institutions. The New Hampshire and North Carolina State Departments of Correction also conduct random searches of their staff. The Alabama Department of Corrections searches staff 2-3 times per year at each institution and randomly searches the parking lots with canine units. In the Pennsylvania State Department of Corrections, random pat searches and property searches are conducted on staff upon entry to institutions. Pennsylvania also uses the ion spectrometry scanning device as part of its staff searches. If the device shows a positive reading for a staff member, that reading can be used as the basis for requiring a urine drug test. The Florida and Kansas State Departments of Correction also use ion spectrometry technology to screen staff. The Maryland Department of Corrections uses canine drug interdiction teams to target staff as well as inmates and visitors.

The BJS report further shows a direct link between interdiction activities focused on staff and reductions in drugs in prisons. The report found that institutions that direct special interdiction efforts toward staff (such as questioning, pat searches, and drug testing of staff) have a lower positive inmate drug test rate (1.0 percent positive for cocaine and 0.9 percent for heroin and methamphetamines) than institutions that made no special efforts to interdict drugs from staff (2.6 percent positive for cocaine, 2.2 percent for heroin, 6.6 percent for methamphetamine).35

At the BOP institutions we visited, several managers and correctional officers previously employed with state correctional systems noted that their previous employers searched staff and prohibited personal property in state institutions. The FBI and OIG agents we interviewed who investigate BOP drug cases also expressed concern that staff and their property are not searched when staff enter institutions. The agents believed the lack of property and staff searches significantly contributed to staff's ability to smuggle drugs into BOP institutions.

Lack of Staff Drug Testing

The BOP Program Statement 3735.04, Drug Free Workplace, June 30, 1997, states that illegal drug use by staff is counter to the BOP's law enforcement mission and will not be tolerated. It also requires random drug testing annually on 5 percent of the staff who are in test designated positions (TDP).36 However, the BOP does not comply with its own policy and does not randomly test any of its staff.

A previous attempt by the BOP to implement random drug testing met with strong union opposition. The American Federation of Government Employees (A.F.G.E.) brought an action in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California and in the U.S. Court of Appeals, 9th Circuit, contesting this random drug testing for BOP employees as unconstitutional. The BOP argued that staff drug use and drug smuggling were connected because drug-using staff are: (1) blackmailed by inmates; (2) in need of money to support their drug habit; and (3) indifferent to drug use and dealing as criminal activities. The BOP also argued that staff drug use causes loss of the public's trust, which leads to the belief the BOP is corrupt or inefficient. In 1993, the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the BOP and held that random drug testing and reasonable suspicion drug testing of BOP employees were constitutional.37

Yet, despite that court ruling, the BOP did not implement random drug testing of staff. When we interviewed the BOP Director, other Central Office officials (Drug Free Workplace Office; Human Resource Management Division, Labor Management Relations; and General Counsel's Office), and union officials, they could not provide specific reasons why the BOP has never implemented random drug testing.

At the institutions we visited, the large majority of more than 100 managers, supervisors, correctional officers, unit managers, and drug treatment specialists we interviewed supported random drug testing of staff. They also noted that the BOP's law enforcement mission and the detrimental effects of drugs on the safety and security of the institution warranted random drug testing. A view expressed by many officers is that they do not want to rely on a drug-using officer as back-up in emergency situations.38 Emergencies usually involve a fight or assault between inmates. In these volatile and dangerous situations, officers want assurance that fellow officers are drug free and can respond quickly and appropriately to an emergency.

Random drug testing of staff is a common practice in state correctional systems and in federal agencies. According to a survey conducted in 2000 by the ACA, 23 of the 44 states that responded conduct random drug testing of their corrections staff.39 The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), in a May 2000 article, reported that approximately 49 percent of jail jurisdictions drug test staff, and of these jurisdictions, 63 percent test staff randomly.40 Additionally, other DOJ components with law enforcement missions such as the FBI, OIG, Drug Enforcement Administration, the U.S. Marshals Service, and the Immigration and Naturalization Service conduct random drug testing of staff.41

Conclusion

The BOP's limited interdiction activities directed toward its staff are not fully effective. Staff continue to smuggle drugs, sometimes in large quantities, into federal institutions. The BOP does not restrict staff property and searches staff infrequently for reasonable suspicion. Consequently, staff can exploit this lax policy to introduce drugs and other contraband into the institution.

The BOP developed but never implemented a drug testing program for staff that included random drug testing of 5 percent of its staff in TDP. The BOP successfully defended a court challenge to its random testing policy in 1993, but has yet to implement the policy.

|

Union Views

We interviewed two union representatives, a national regional vice-president and a local BOP institution president representing the national union, Council of Prison Locals 33, American Federation of Government Employees, American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (A.F.G.E., AFL-CIO), about the BOP's drug interdiction activities. The representatives believed contact visits are the number one source of drug introduction. They also believed packages coming through the rear gate (via delivery from the warehouse) present vulnerabilities for the institutions. Due to the high volume of packages, the one officer assigned to the rear gate can only randomly search packages for contraband. The union representatives also stated that at some institutions, staff are permitted to pick up small packages from the warehouse and walk them into the institution without being searched. According to the union representatives, the BOP's background investigations of staff and annual integrity training are insufficient drug interdiction activities. They stated that more aggressive prosecution of staff involved in drug activities represents the best deterrent. According to the representatives, compromised staff are sometimes permitted to resign in lieu of administrative sanctions and prosecution. As a result, the misconduct is undocumented and the number of drug cases involving staff are underreported. Regarding additional drug interdiction activities needed, the representatives suggested that BOP canine units should be posted at the front entrance and rear gate of every institution. At the front gate, they can search staff as well as visitors, and at the rear gate they can search all packages for drugs. The representatives stated drug dogs are a strong deterrent but they must be present on a daily basis. When drug dogs from outside law enforcement are used, inmates often become aware of these plans in advance and the searches are ineffective. The representatives also support drug testing for staff and are unsure why the BOP Drug Free Workplace policy was never implemented [after the 1993 court ruling]. The union representatives also stated they are not opposed to placing limited restrictions on staff personal property entering institutions, recognizing that staff still need to bring their lunches. However, the representatives are opposed to random searches of staff or their property because they are concerned about potential disparate treatment of staff during searches, how staff would be selected for searching, and the impact on staff morale. The representatives would prefer to see additional interdiction activities directed toward inmates and visitors before searching staff and their property. The union representatives did not oppose the use of advanced technology, such as trace drug detection and imaging technology (walk-through and hands-free) that would be applied equally, not randomly, to all persons entering institutions. The union representatives recognized that inmates compromise some BOP staff, resulting in the introduction of contraband into the institutions. They stated that staff do not wake up one day and say, "I'm going to bring drugs in today." Some staff get inappropriately involved with an inmate such as granting an inmate a favor or bringing in soft contraband, then they are "hooked." The inmate threatens to report the staff member for the less serious misconduct unless the staff member does what the inmate wants. The representatives do not believe the BOP views drugs as a top priority. Additional points made by the representatives were: (1) the SIS lieutenant position should be permanent, with an independent reporting structure outside of the institution; (2) more frequent shakedowns of institutions are needed, and (3) more specialized training for staff to update drug interdiction skills is needed. |

Officials from the BOP's Central Office and institution staff told us that inmates and their outside contacts also use the mail to smuggle drugs into the institutions. Most staff interviewed during our visits reported concern about inmate abuse of mail. However, they reported that inspecting thousands of mail items each day per institution for illegal drugs typically results in only a few drug finds BOP-wide each year. The BOP's automated evidence records contain only 24 drug finds attributed to inmate mail from FY 2000 through FY 2001. Given the continued smuggling of illegal drugs in the BOP's institutions, institution staff stated BOP could reduce the mail's vulnerability to drug smuggling by (1) limiting the receipt of certain publications, (2) training staff on drug detection, and (3) screening mail with drug detection technology.

Volume of Incoming Inmate Mail Challenges Interdiction Activities

At the institutions we visited, Inmate Systems Management Officers (ISOs), who are responsible for the mailroom function, stated that they do not detect all attempts to smuggle drugs through the mail. The daily volume of mail, especially the increasing volume of unsolicited catalogues and other publications, is too great for thorough manual inspection. The ISOs often do not have drug detection technology to aid their inspections of the mail.42 BOP mailrooms process up to 3,000 pieces of mail each weekday, depending on the size and security level of the institution and the day of the week.43 Because the institution's mail is not delivered on weekends, the volume of all mail received on a Monday could represent an increase in volume of up to double the volume received on a typical Tuesday through Friday. The volume of mail doubles during holiday periods.

More Controls are Needed Over Incoming Publications

Inmates have used incoming publications sent from families and friends as a means for smuggling drugs into institutions. In 1999, to minimize opportunities for smuggling, the BOP implemented a policy that allowed inmates to receive hardcover books and newspapers only from a publisher, book club, or bookstore.44 However, softcover books and magazines still can be sent by families and friends and still are used to smuggle drugs. The BOP recognizes this security vulnerability and is seeking approval from the Office of Management and Budget for a new policy to prohibit inmates' receipt of softcover publications from inmates' families and friends.45

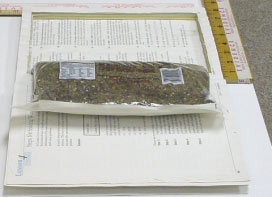

The implementation of restrictions on both hard and softcover publications will reduce but not eliminate inmates' use of the mail to smuggle drugs into BOP institutions. The ISOs told us that inmates continue to receive mail disguised by inmates' outside contacts to appear as if it were sent directly from approved sources. For example, Figure 2 below and on the next page shows newspapers containing drugs that were sent to inmates at a high security institution.

Figure 2. Newspapers with Marijuana Disguised as Publisher-Sent

Source: BOP |

The inmates' outside contacts affixed counterfeit mailing labels to the newspapers to make them appear as having been sent directly by authentic publishers.

Source: BOP Packets of marijuana hidden between glued together newspaper pages. |

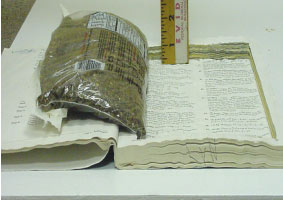

In another scheme, an inmate at an institution we visited arranged for an incoming hardcover publication to be disguised as official institution mail sent directly from an approved supplier to the institution's Facilities Department. The inmate's outside contact created fictitious supplier mailing labels (the address details were provided by the inmate who worked in the Facilities Department) based on previous legitimate mail items sent by the supplier and regularly received by the department. Figure 3 below and on the next page shows the hardcover book that was hollowed out and filled with drugs.

Figure 3. Hardcover Textbook with One-Half Pound of Marijuana

Source: BOP |

Source: BOP |

The ISOs at the institution where this drug introduction occurred did not detect the presence of the drugs when the book was initially received and x-ray scanned.46 Institution staff within the Facilities Department inspected the textbook and discovered the drugs.

Unsolicited Mail Adds to Security Problems. At the institutions we visited, ISOs stated that policies are needed to limit the growing volume of unsolicited mail, such as catalogs, brochures, and fliers, received by inmates. This type of mail can comprise 10 percent or more of all daily mail received by an institution. The continued need for ISOs to process and inspect large quantities of unsolicited mail, in addition to thousands of other general and legal mail items received daily, challenges an institution's ability to interdict drugs. The ISOs told us drugs enter institutions through the mail because inmates are sophisticated in hiding drugs, and staff hand searching each page of every publication is not feasible given the volume of mail. Some state correctional systems, such as Connecticut, Illinois, and Oklahoma, prohibit inmates from receiving unsolicited advertisements or publications.

Special Handling Requirements for Legal Mail Complicate Drug Interdiction Activities

Legal mail, consisting of congressional, judicial, and attorney mail, requires special handling.47 BOP Program Statement 5265.11, Correspondence, limits the authority institutions have to inspect incoming inmate legal mail:

The Warden shall open special [legal] mail only in the presence of the inmate for inspection for physical contraband and the qualification of any enclosures as special mail. The correspondence may not be read or copied if the sender is adequately identified on the envelope, and the front of the envelope is marked "Special Mail - Open only in the presence of the inmate."

As a result of these requirements, the authorized limited inspection of inbound legal mail for contraband does not occur until the item is opened by staff in the presence of the inmate.48 Typically the ISOs transport the legal mail to the individual housing units where the unit management staff open and inspect the legal mail in the presence of the appropriate inmates, and give the mail to the inmates after they sign for its receipt. At some institutions, inmates receive legal mail at a designated time in the mailroom where ISOs or intelligence officers open, inspect, and turn over the legal mail to the inmates.

The ISOs at the institutions we visited and one Inmate Systems Management official at the BOP's Central Office described inmate legal mail as the weakest link in the ISOs' ability to detect drug contraband. The ISOs expressed concern about the consistency, quality, and thoroughness of inspections performed on legal mail at BOP institutions, in particular once the legal mail is forwarded to the inmate housing units where inspection for contraband and delivery to inmates takes place. These inspections may consist of only a brief hand and visual review for obvious contraband. Often the legal documents are thick and bound together in a way that makes inspection difficult. These ISOs also stated that some newer and less experienced unit management staff may perform a less rigorous inspection. They further stated that the unit managements' competing tasks and the distractions that occur on a daily basis within a housing unit may interfere with the thorough inspection of legal mail. These concerns are heightened because of the BOP's inmate population growth and corresponding complement of newer staff.

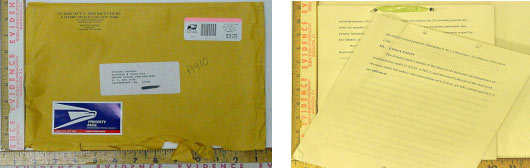

The ISOs also stated that verifying the authenticity of incoming legal mail is difficult. Regular mail has been disguised as legal mail with fictitious legal names and addresses, which may go undetected because the ISOs do not know the legitimate legal representatives for individual inmates. Figure 4 shows an attempt to smuggle heroin into a USP using a document disguised as legal mail that was detected during inspection by mailroom staff.

Figure 4. Heroin Hidden Within the Binding of a Document Disguised as Legal Mail

Source: BOP |

Source: BOP |

Figure 5 on the next page shows an attempt by an outside gang member (also a former inmate) to introduce 11 grams of methamphetamine into a high security institution using a document disguised as legal mail and sent to an inmate. He concealed the drugs in a hollowed portion of the glued-together binding of the document. The BOP detected and prevented delivery through intelligence gathered from monitoring the inmate's telephone calls.

Figure 5. Methamphetamines Hidden Within Glued Binding of Document Disguised as Legal Mail

Source: BOP |

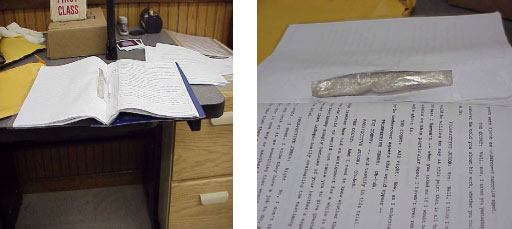

The ISOs also expressed concern about outgoing legal mail, which can be used to facilitate the introduction of drugs. For example, in a criminal case investigated by the OIG, the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, and the BOP, a cooperating defendant provided investigators with inmate correspondence disguised as outgoing legal mail, which detailed a drug introduction scheme and had been successfully mailed by an inmate from a high security level institution. The fraudulent legal mail was addressed to an actual attorney, but the postal address was not the attorney's address. Instead, the postal address was that of the inmate's outside contact. The inmate's correspondence contained five handwritten pages of instructions on how to use legal mail to hide 16 grams of heroin in balloons in the binding of a legal document.

BOP staff authority for outgoing legal mail is even more restricted than for incoming legal mail, because outgoing legal mail may be sealed by the inmate and is not subject to inspection.49 The ISOs are required to stamp outgoing legal mail with the statement:

The enclosed letter was processed for forwarding to you. The letter has neither been opened nor inspected. If the writer raises a question or problem over which this facility has jurisdiction, you may wish to return the material for further information or clarification. If the writer encloses correspondence for forwarding to another addressee, please return the enclosure to the above address.

Staff stated that their limited authority over outgoing (and incoming) legal mail impedes their ability to detect and deter criminal activity. Inmates are aware of this limited authority and therefore use legal mail as a means of introducing drugs and other contraband into BOP institutions.

Staff Training on Drug Detection is Limited

The ISOs and unit management staff stated they need, as do all staff, standardized and more rigorous drug interdiction training to better inspect inmate mail for drug contraband. Staff said they need more familiarity with different types and forms of drugs, and the methods used by inmates to bring drugs into institutions. In many cases, staff reported their first exposure to recognizing and detecting certain categories of drugs, such as black-tar heroin, came only after a successful detection by another officer. At one high security institution we visited, an intelligence officer created a picture storyboard using actual drug finds within the institution to help educate other staff. The storyboards are used in local new officer training and annual refresher training for all institution staff.

Technology in Use is not Suited for Detecting Drugs

We found that drugs may go undetected through all stages of mail inspection because of inadequate technology or human error. At each institution visited, ISOs stated new technology is needed that will more readily identify drugs concealed in the mail. The BOP Program Statement 5800.10, Mail Management Manual, encourages its institutions to supplement mail inspection activities with modern technology. The BOP Office of Security Technology (OST), which is responsible for identifying new security technologies and evaluating their potential use in the BOP's institutions, describes the use of x-ray devices as "our first defense in the mail drug interdiction effort." In practice, while x-raying mail may produce suspicious images leading to closer staff scrutiny and subsequent drug finds, x-ray scan devices are primarily designed to help the ISOs better detect metal weapons and explosive devices. Even at those sites we visited with more recent generations or upgrades of the x-ray scan technology, many experienced ISOs cautioned against high expectations for this technology for detecting drugs. They said few drug contraband finds actually occur during the x-ray inspection. If drugs are detected, it usually occurs during the subsequent labor-intensive manual inspections performed by ISOs.

The OST evaluated the following drug detection technologies and stated they possessed promise for mailroom application:

According to the OST, the BOP does not have immediate plans to implement or test mailroom drug detection technologies. The BOP has not deployed additional technologies to its institutions because of concerns over cost and reliability. During our interviews, the absence of centralized funding for these technologies was cited as the main deterrent to pilot testing or BOP-wide implementation. Officials at the institutions we visited stated that local funding of drug-screening technology is not always possible because of budget constraints and competing priorities.

Conclusion

BOP staff consider the institution's mail system to be a significant point of entry for drugs. The daily volume of inmate mail, special handling procedures for legal mail, limited staff training, and inadequate technology present specific challenges for effective detection of drugs in the mail. The BOP manually inspects inmate mail to detect drugs, but ISOs believe these inspections cannot detect all drugs.

REDUCING THE INMATES' DEMAND FOR DRUGS THROUGH DRUG ABUSE TREATMENT

Drug abuse treatment programs for inmates are a significant part of the BOP's strategy to reduce drugs from its institutions.50 However, the BOP does not treat all inmates who have drug problems because not all inmates' diagnoses and drug treatment recommendations are recorded in SENTRY. The inmates' treatment needs are therefore inadequately tracked throughout their incarceration. As a result, the BOP is not allocating sufficient resources to meet the recommended treatment needs of all inmates. Moreover, the BOP only treats a portion of the inmates it estimates need treatment. The BOP focuses on drug abuse education (classroom instruction) and the residential (in-patient) drug abuse program (RDAP).51 The BOP does not ensure inmates have access to BOP non-residential (out-patient) treatment after completion of drug abuse education classes or before admittance to the RDAP.52 Even if an inmate meets the eligibility criteria for the RDAP, the waiting time for placement can be years.

The BOP Underestimates the Drug Abuse Treatment Needs of Inmates

In its FY 2001 Report to Congress on Substance Abuse Treatment Programs, the BOP states that 34 percent of its inmates have a substance abuse disorder.53 This 34 percent figure is low compared to other federal, state, and local corrections data. For example:

To arrive at the 34 percent figure, the BOP administered a Substance Abuse Needs Assessment in the summer of 1991 during a 3-month period. Every inmate entering the BOP completed an Inventory of Substance Abuse Patterns. From these inventory responses, the BOP determined that 30.5 percent of the inmates met the criteria for drug dependence as defined by the DSM-IIIR.57 In 1997, this figure was updated using the "Survey of Inmates in Federal Correctional Facilities," conducted by the U.S. Bureau of Census, the BJS, and the BOP. Using the DSM-IV criteria published in 1994, the BOP extrapolated drug symptomology data from this survey for drug dependence (most serious drug use) and abuse (recurrent use but less than dependence) and the percentage of inmates it estimated had substance abuse disorders increased to 34 percent. 58

The BOP is relying on outdated, estimated data to determine the number of inmates with drug abuse treatment needs. We believe the BOP should rely instead on diagnoses made at BOP institutions by psychologists and DATS.59

Tracking Inmates with Drug Abuse Treatment Needs is Insufficient

The BOP's Central Office (Psychology Services Branch) could not provide us with BOP-wide data (generated from the automated SENTRY database) describing the treatment needs of inmates, referrals for treatment, and actual treatment of inmates. Consequently, without capturing this information in SENTRY, the BOP cannot identify, track, or monitor inmates with diagnosed drug problems to encourage treatment. Nor can the BOP allocate sufficient staff resources to provide the treatment programs. Without the BOP-wide data, the BOP is unable to determine the actual number of inmates in need of drug treatment.

In each institution, a psychologist conducts a psychological assessment within four weeks of an inmate's admission to the BOP. A drug abuse screen is part of that assessment.60 If drug treatment is indicated, the psychologist sends a paper copy of the recommendation to the inmate's unit manager, but that recommendation is not always recorded in SENTRY. An institution only documents an inmate's drug treatment needs in SENTRY when:

An institution excludes from SENTRY:

By not including every diagnosed and recommended drug treatment need in SENTRY, the BOP does not know the accurate number of inmates with drug problems and treatment referrals.

Non-Residential Drug Abuse Treatment is Not Always Available

Even though many inmates would benefit from non-residential drug treatment, it is not always available at BOP institutions because of insufficient drug treatment staff, lack of policy guidance, and lack of incentives for inmates to seek drug treatment. Non-residential treatment is out-patient treatment and includes individual and group therapy for inmates in the general population. At the institutions we visited, the BOP emphasized drug abuse education and the RDAP, but placed minimal emphasis on non-residential drug treatment. As a result, only a limited number of general population inmates receive non-residential treatment.

According to the drug treatment staff at the institutions we visited, drug abuse education classes usually were offered continuously and the RDAP was encouraged for those inmates who met the criteria. However, drug abuse education is not treatment but rather a series of classes designed to provide information about the detrimental consequences of drug use through literature and videos. Further, the RDAP is not offered at all institutions (none of the institutions we visited offered the RDAP), and where it is offered, inmates are not eligible for participation until the last 36 months of their sentence.61 The average BOP inmate sentence length is ten years. Consequently, an inmate could wait seven years or more before receiving residential drug treatment. In the interim, inmates are dependent on non-residential drug treatment to meet their immediate treatment needs because it is the only drug treatment available in the institution for the general inmate population before admittance to the RDAP. Yet, non-residential drug treatment programs were not offered at all institutions we visited. Even at most institutions where it was offered, it was offered irregularly.62

The BOP's internal program reviews have reported ongoing deficiencies in providing non-residential drug treatment.63 Selected Program Summary Reports containing cumulative findings from individual program reviews conducted from FY 1998 through FY 2001 state the following deficiencies:

Associate wardens and unit managers at several institutions we visited acknowledged there were insufficient drug treatment programs for inmates at their institutions. Drug treatment staff at five of the institutions visited stated their program emphasized residential treatment and not non-residential treatment. The drug treatment staff stated while drug treatment may be a priority at minimum and low security level institutions, security, not treatment, is the priority at the medium and higher security level institutions.

Of particular note are the low drug treatment rates at institutions with high drug use rates and drug misconduct charges, such as three of the four USPs and one of the two FCIs we visited. For example:

According to the BOP's Program Statement 5330.10, Drug Abuse Programs Manual, self-help programs such as Narcotics Anonymous or Alcoholics Anonymous are often associated with non-residential treatment and may be offered as part of an institution's non-residential drug treatment program. Although not considered treatment, the BOP recognizes that these self-help groups can be an important intervention in an inmate's recovery. However, even these self-help groups did not exist in all the institutions we visited. Some institutions had not requested assistance from Narcotics Anonymous or other volunteers in the community. Other institutions stated the criminal backgrounds of some Narcotics Anonymous volunteers, who are often former drug addicts, preclude their presence in the institutions.

The cumulative effect of limited non-residential treatment, few self-help groups, and the restrictive timeframe (36 months prior to release) for RDAP eligibility is that not enough inmates receive drug abuse treatment. According to the BOP, in FY 2001 26,268 inmates received drug abuse treatment either through residential treatment (15,441) or non-residential treatment (10,827).64 The BOP's outdated and low estimate is that 34 percent of its population needs drug abuse treatment. Therefore using BOP's estimate of 34 percent, in FY 2001, based on an average daily inmate population of 133,642, approximately 45,438 inmates needed treatment. As we discussed above, the actual number who need treatment is likely much higher. Yet, only 26,268 inmates, or 57.8 percent of those inmates with estimated treatment needs, received residential or non-residential drug treatment. The other 19,170 inmates (42.2 percent) did not receive any treatment. This low treatment rate is a significant deficiency in the BOP's demand reduction strategy.

Limited Drug Treatment Staffing Restricts Comprehensive Drug Treatment Programs

The BOP's staffing guidelines suggest each institution needs one DATS per 1-500 inmates, which would equate to two to four DATS for each institution we visited. The FY 2001 average daily population for the institutions we visited ranged from 1,322 to 2,012 inmates. However, at these institutions, only one DATS per institution was employed to provide drug treatment programs to inmates.65 The DATS stated they were overwhelmed at times with their duties and the number of inmates who need help. They believed providing drug abuse education several times per week to many groups of inmates at different sites, with all the related paperwork, was a full-time endeavor. The DATS further believed developing and leading non-residential group or individual counseling, especially if inmate participation increased through incentives, was not feasible without additional drug treatment staff.

The qualifications of a DATS may also affect the availability of non-residential drug treatment because the DATS may not be clinically trained to facilitate a group or individual counseling session. At one USP with a high drug use rate, the DATS had no counseling background or related qualifications and training skills needed to provide individual or group treatment.66 With only one DATS per institution (and also serving a satellite camp), having someone with the appropriate counseling qualifications is imperative for providing drug treatment to inmates, not just drug abuse education.67

Policy Lacks Clarity for Non-Residential Drug Abuse Treatment

The BOP's Program Statement 5330.10, Drug Abuse Programs Manual, states non-residential treatment services shall include a minimum of one hour of individual or group contacts each month as indicated by a treatment plan. It also states that transitional services, a component of non-residential drug treatment, are required one hour per month for RDAP graduates. At some of the institutions visited, the treatment staff believed that the mandatory transitional services offered to RDAP graduates fulfill the institution's requirement to provide the monthly one hour of non-residential drug treatment. However, transitional services focus on relapse prevention and aftercare, which may not be appropriate for inmates who have never had any prior drug treatment. The program statement does not provide clear direction that, besides transitional services, other non-residential drug treatment must be provided for inmates who have not completed the RDAP.

The program statement also does not provide a curriculum or outline for non-residential drug treatment groups, and does not suggest a minimum duration for effective treatment. Yet, for drug abuse education and the RDAP, specific standardized written curricula and timeframes are provided. Without clear policy direction for non-residential treatment, DATS have focused their efforts on drug abuse education and the RDAP. This limited focus leaves many inmates without drug treatment during most of their incarceration.

Policy Lacks Incentives for Participation in Non-Residential Drug Abuse Treatment

Drug abuse education classes and the RDAP reward inmates for completing the program and impose sanctions for non-completion. Non-residential drug treatment does not reward or sanction the inmates. For example, drug abuse education, a 30-40 hour course, is mandatory within the first 12 months for all inmates who meet the criteria (see Appendix I). Inmates who refuse to participate or fail to complete the drug abuse education classes are held at the lowest pay grade ($5.25 per month) and are ineligible to participate in community programs. Inmates eligible for RDAP have even stronger incentives for participation and completion of the program. The incentives include but are not limited to: (1) up to 12 months early release from prison, (2) limited financial rewards - up to $180, and (3) local institution incentives such as preferred living quarters. Conversely, inmates who fail to complete the RDAP are no longer eligible for these incentives.

Because there are no incentives or sanctions for non-residential drug treatment, staff stated that inmates do not readily volunteer to participate in that treatment. At the USPs we visited, drug treatment staff stated that many inmates are "long term convicts and long time addicts" with many years of incarceration to serve and minimal interest in treatment. Therefore, to motivate these and other inmates to participate in drug treatment, unit management and drug treatment staff believe that the BOP must "use the carrot and stick approach" by developing incentives. Conversely, if an inmate is referred for non-residential drug treatment but does not volunteer or successfully complete the treatment, staff believe the inmate should face loss of privileges. Suggestions for incentives included preferred living quarters, additional points for visits, and permission to order a special food item through the institution's commissary. However, these staff did not favor the incentive of reducing an inmate's sentence because they believe the motivation for treatment would be insincere. Inmates entering the BOP's institutions often tell the drug treatment staff, "I want the time-off program," referring to the RDAP where inmates can receive up to 12 months off their sentence for successful completion of residential treatment.

Unit managers and drug treatment staff also strongly believed that inmates referred for drug treatment should be rated on their participation through a separate category on the annual Security Designation and Custody Classification Review form.68 If an inmate fails to complete recommended drug treatment, then the inmate should receive a score of "zero," which would preclude the inmate from receiving a lower security level designation, being recommended for community programs, or receiving pay above the lowest pay grade. Under the current review procedures, drug treatment participation is combined with many other factors. These other factors include interaction with staff and other inmates, misconduct reports, participation in other recommended activities, work reports, and paying court related fines. Combining drug treatment participation with these other factors minimizes the weight given to whether or not inmates participated in and completed the drug treatment. Thus the BOP's emphasis on drug treatment becomes diminished when mixed with other unrelated factors. Unit managers stated that they only can score an inmate "zero" on their annual Security Designation and Custody Classification Review if the inmate fails to fulfill the requirements of the Inmate Financial Responsibility Program, (i.e., paying court related fines, penalties, and restitution). They believe the same should apply to successful completion of drug treatment programs.

Conclusion

Reducing inmates' demand for drugs through drug treatment programs is a significant part of the BOP's strategy to eliminate drugs from its institutions. However, this part of the BOP's strategy has not been fully effective. The BOP's estimate that 34 percent of inmates need drug treatment is low, according to drug treatment staff at the institutions visited and outside organizations that have gathered data on inmate drug use. These staff and organizations have stated that the percent of federal inmates with drug problems ranges from at least 50 to 80 percent. Substantially more BOP inmates may need treatment than recognized by the BOP's 34 percent figure and its associated insufficient drug treatment resources.

Drug treatment and unit management staff at the institutions we visited also stated that the BOP emphasizes and directs resources towards drug abuse education and the RDAP. But without non-residential drug treatment, inmates must wait until the last 36 months of their sentence for possible admission into the RDAP - a potential waiting time of years. Thus, a void in drug treatment exists between drug abuse education and the RDAP. The result is not enough inmates receive drug treatment, even when the BOP's low estimate of 34 percent is used as the baseline of inmates' treatment needs.

OTHER OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE DRUG INTERDICTION

We reviewed other potential points of entry for drugs - the receiving and discharge area, the warehouse, the rear gate, volunteers, and contractors - that BOP staff stated were less vulnerable to drug smuggling. Regarding the receiving and discharge area, the warehouse, and the rear gate, we concluded better technology could supplement manual searches for drugs by correctional officers. For volunteers and contractors, we concluded that shared information about their backgrounds could assist institutions in their selection decisions. We also reviewed the role of institutions' intelligence staff in drug interdiction activities and concluded that rotation of the SIS lieutenant is too frequent, and timely investigative and drug training is needed. Lastly, we reviewed the BOP's only canine unit located at USP Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, and concluded canine units may be a useful drug interdiction technique for other institutions.

Although the receiving and discharge (R&D) area is not a primary point of entry for illegal drugs, inmates sometimes attempt to introduce drugs as well as other contraband upon initial commitment, during transfers between BOP institutions, or upon return from external temporary releases, such as emergency medical care or court appearances.70 The primary objective of R&D is to ensure inmates are committed and discharged appropriately and all inmate property is processed without introducing contraband.71

The ISOs at the institutions we visited cited examples of inmate schemes to conceal contraband inside personal commissary items when transferring from one BOP institution to another. Inmates are permitted to take unopened commissary items with them when transferring to another institution. Some inmates take advantage of this privilege by opening their commissary items, hiding contraband, then resealing and disguising the commissary item to make it appear new. Figure 6 on the next page shows one attempt by an inmate to conceal bomb-making substances in a commissary item.

Figure 6. Ingredients for Explosive Device Found Hidden Among an Inmate's Personal Commissary Items.

Source: BOP |

While the ISOs stated that most smuggling attempts are discovered during R&D inmate property inspections, they also stated that inmates' demand for drugs and their ingenuity in concealing contraband in commissary items increases the probability that contraband goes undetected.

Thorough R&D inspections for contraband are critical to maintaining the safety and security of each institution. R&D inspections generally consist of pat and visual or strip searches of inmates, including the use of hand-held metal detectors and x-ray body cavity searches (if technology is available at the institution), as well as manual, visual and x-ray inspections of all inmate property.72 The x-ray scan technology for body cavity searches and property inspections recognizes metal objects but not drugs. Figure 7 on the next page demonstrates the effective use of the body cavity x-ray scan technology for detecting metal contraband and the value of integrating technology with traditional manual interdiction activities. Figure 7 also illustrates the ingenuity of and risks taken by inmates to introduce contraband.

Figure 7. Photographs Showing Metal Contraband Detected Using Body Cavity X-Ray Technology

Source: BOP The body cavity x-ray image on the left shows a hacksaw blade and paper clip.

|

BOP encourages the use of x-ray scan devices in R&D to supplement manual and visual inspections of personal property. All institutions do not have x-ray scanners in the R&D areas, but instead could use the scanners located in the warehouse or at the institution's front entrance. However, this arrangement does not encourage scanning of inmates' suspicious property because the x-ray scanners available to R&D are inconveniently located outside the institutions' secure perimeter fencing while the R&D area is located within the secure perimeter fencing.

Institution Deliveries: The Warehouse and Rear Gate

The institutions we visited use various visual and manual search procedures along with x-ray technology to inspect daily deliveries entering through the institutions' warehouses (dry and cold storage, and UNICOR) and rear gate.

Interdiction activities for incoming deliveries are labor intensive and usually target hard contraband, primarily weapons and explosive devices. As deliveries arrive at a warehouse receiving dock (usually located just outside an institution's perimeter fence), a standard inspection for the correct quantity and acceptable quality of the delivered items is conducted followed by an inspection for contraband. To perform the contraband inspection, warehouse staff conduct a complete or random visual and manual inspection of shipments. While some deliveries consist of individual parcels or packages, most deliveries consist of shrink-wrapped pallets containing bulk deliveries of perishable and non-perishable food products and other supplies necessary to support the institution's needs.73

Supplemental use of imaging and detection technology to enhance contraband interdiction activities varies by institution. For example, at one USP we visited, inspection of daily deliveries consists primarily of manual and visual inspections and use of a hand-held wand metal detector because the warehouse did not have its own x-ray scan device. The only available x-ray scan device (for small packages) was located in the mailroom in an adjacent building. Both the location of the device and its limited capacity size deterred the use of x-ray technology by warehouse staff.

In contrast, another USP we visited used additional inspection procedures for all of its deliveries. Inbound deliveries at the warehouse receiving dock were subject to visual and manual inspections for contraband. Upon leaving the warehouse, all deliveries were inspected using x-ray technology located in a stand-alone x-ray building positioned midway between the warehouse facility and the rear gate of the USP. This is the only institution we visited equipped with x-ray technology capable of handling pallets or skids weighing up to 500 pounds. The technology allows scanning of the pallets or skids from four sides rather than from only a top view provided by typical x-ray scan devices used in most institutions. The bulk imaging device is equipped with two monitors, which provide enhanced imaging to better identify and distinguish between non-organic materials (weapons) and organic materials (drugs and explosives). While staff reported increased confidence in the improved x-ray scan device, they also emphasized the importance of assigning staff specifically trained and experienced in all methods of contraband detection given the volume of deliveries entering the institution's secure perimeter each day.

At all institutions, after inspecting deliveries at the warehouse, rear gate staff conduct another complete or random inspection for contraband before admitting the shipment within the institutions' secure perimeter fencing. The rear gate inspection is visual and manual; sometimes a hand-held wand metal detector is used to scan the contents of boxes and packages. The delivery vehicles also are searched for hidden contraband.

Conclusion

BOP inmates transferring to other institutions through the R&D area may attempt to hide contraband in commissary items disguised as new and unopened. Under the BOP's current policy, these items are not easily detected. Institutions also receive a high volume of deliveries through their warehouse and rear gate areas each day. Inspection of these deliveries is labor intensive and often conducted without the benefit of technology designed for bulky items and large pallets. The limited x-ray devices available do not readily detect the presence of drugs. The R&D area, the warehouse, and the rear gate operations could benefit from advanced imaging and detection technology to supplement current search techniques.

Volunteers and contractors supplement the programs and services BOP provides to inmates. Because of the extended contact volunteers and contractors have with inmates - contact that is not always under direct observation by the BOP staff - volunteers and contractors have the opportunity to develop inappropriate relationships with inmates, which may lead to attempts to smuggle contraband.

According to the BOP, in FY 2001 31,879 volunteers made 152,015 visits to BOP institutions nationwide.74 During the first two quarters of FY 2002, 24,672 volunteers made 78,018 visits to its institutions. Given the number of volunteers that enter the institutions on a yearly basis, significant opportunities exist for their smuggling drugs into the institutions. Data provided to us by the Volunteer Management Branch at the BOP's Correctional Programs Division showed dismissals of volunteers for drug-related charges are rare.75 According to the data, which contains dismissal information from 1994 to 2001, only 5 of the 55 volunteer dismissals were related to the introduction of contraband, and only 1 of these 5 dismissals was for smuggling drugs. Inappropriate relationships or contact with inmates, previously undisclosed criminal histories, or previously undisclosed family or personal relationships with inmates prior to volunteering are the reasons for most volunteer dismissals.