USDOJ/OIG - Semiannual Report to Congress, October 1, 1998 - March 31, 1999 |

Page 20 |

The Audit DivisionThe Audit Division is responsible for independent reviews of Department of Justice organizations, programs, functions, computer technology and security systems, and financial statement audits.

|

USDOJ/OIG - Semiannual Report to Congress, October 1, 1998 - March 31, 1999 |

Page 21 |

Audit Division

The Audit Division (Audit) reviews Department organizations, programs, functions, computer technology and security systems, and financial statements. Audit also conducts or oversees external audits of expenditures made under Department contracts, grants, and other agreements. Audits are conducted in accordance with the Comptroller General's Government Auditing Standards and related professional auditing standards. Audit produces a wide variety of audit products designed to provide timely notification to Department management of issues needing attention. It also assists the Investigations Division in complex fraud cases.

Audit works closely with Department management to develop recommendations for corrective actions that will resolve identified weaknesses. By doing so, Audit remains responsive to its customers and promotes more efficient and effective Department operations. During the course of regularly scheduled work, Audit also lends fiscal and programmatic expertise to Department components.

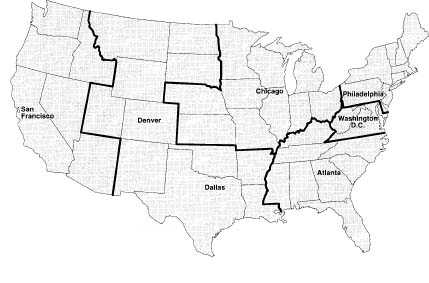

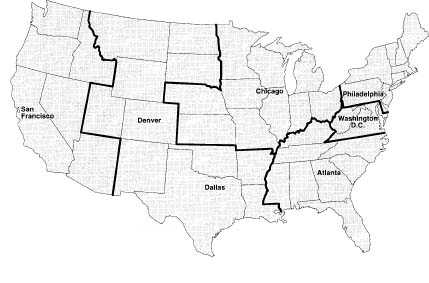

Audit has seven field offices across the country—in Atlanta, Chicago, Dallas, Denver, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C. Audit's Financial Statement Audit Office and Computer Security and Information Technology Audit Office also are located in Washington, D.C. Audit Headquarters consists of the immediate office of the Assistant Inspector General for Audit, the Office of Operations, the Office of Policy and Planning, and an Advanced Audit Techniques Group. Auditors and analysts have formal education in fields such as accounting, program management, public administration, computer science, information systems, and statistics.

The field offices' geographic coverage is indicated on the map below. The San Francisco office also covers Alaska and Hawaii.

During this reporting period, Audit issued 13 internal reports of programs funded at more than $104 million; 45 external reports of contracts, grants, and other agreements funded at more than $100 million; 78 audits of bankruptcy trustees with responsibility for

USDOJ/OIG - Semiannual Report to Congress, October 1, 1998 - March 31, 1999 |

Page 22 |

Overview and Highlights

funds of more than $163 million; and 59 Single Audit Act audits. Audit issued five Management Information Memoranda, one Technical Assistance Memorandum, one Investigative Assistance Memorandum, and two Notifications of Irregularity.

Office of Community Oriented Policing Services

We continue to maintain extensive audit coverage of the COPS program. The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (Crime Act) authorized $8.8 billion over six years for grants to add 100,000 police officers to the nation's streets. During this reporting period, we performed 22 audits of COPS and OJP police officer hiring and redeployment grants. Our audits identified more than $7.6 million in questioned costs and more than $10 million in funds that could be put to better use. We initiate audits based on requests from the COPS office and OJP, allegations of misuse of grant funds, and selection by Audit. COPS findings to date may not necessarily be representative of the universe of grantees. This is because, as a matter of policy, COPS has referred to us what it suspects might be its riskiest grantees. Our results to date, therefore, may be skewed to problem grantees. We credit COPS with this proactive approach to grants management.

Our audits focus on (1) the allowability of grant expenditures, (2) the source of matching funds, (3) implementation or enhancement of community policing activities, (4) efforts to fill vacant sworn officer positions, (5) plans to retain officer positions at grant completion, (6) grantee reporting, (7) an analysis of supplanting issues, and (8) documentation of efforts to redeploy officers to community policing.

Our findings indicate that significant numbers of the jurisdictions we audited are (1) overestimating salaries and benefits or including unallowable costs in reimbursement requests, (2) using federal funds to supplant local funds, (3) not making a good faith effort to fill locally funded sworn officer positions, (4) not submitting or submitting late status reports to COPS and OJP, and (5) not fully implementing community policing. In addition, we have significant concerns about officer retention and redeployment.

Grantees must maintain COPS-funded officer positions for a minimum of one full budget cycle following expiration of the federal grant. Some jurisdictions may have difficulty retaining COPS-funded officer positions with local funds at the conclusion of the grants. This requirement may have an impact on COPS' goal of deploying 100,000 additional police officers into community policing.

Hiring grants require recipients to hire and maintain the required number of additional officers on the street, which is relatively easy to implement, monitor, and measure. Redeployment grant recipients must buy technology or hire civilians to free up existing officers so that portions of their time may be used for community policing instead of administrative tasks. These activities are much more difficult to implement, monitor, and measure, particularly for redeployment grants that fund technology purchases. Our audits of redeployment grants have led to concerns about the large number of redeployed officers being counted toward the 100,000 goal, the frequency of our audit findings that grantees cannot demonstrate that the required number of officers have been or will be redeployed to community policing, and the greater risk of misuse of funds.

USDOJ/OIG - Semiannual Report to Congress, October 1, 1998 - March 31, 1999 |

Page 23 |

Significant Audit Products

Year 2000 Computer Problem

The Y2K computer problem stems from computer systems' inability to distinguish the twentieth from the twenty-first century with a two-digit year abbreviation (i.e., "00" could be read as the year "1900" or the year "2000"). The federal government is particularly vulnerable because its mission-critical systems process and deliver vital public services. According to the Justice Management Division (JMD), the Department budgeted more than $1.5 billion for information technology investments for FY 1999. As of February 1999, the Department estimates it will spend approximately $150 million on Y2K problems.

During this reporting period, we began a series of Y2K audits of Department computer systems. Our first audit was of the Justice Data Centers (JDCs) because many aspects of the Department's mission depend on computer processing at the JDCs. We found that not all JDC-maintained software tools and utilities were Y2K compliant; Y2K contingency plans were not developed; and Y2K testing of hardware, operating systems, and software tools and utilities was not performed. As a result, data processing at the JDCs could be at risk of failure on January 1, 2000, potentially affecting mission-critical litigation, law enforcement, and administrative systems. During and at the conclusion of our audit, JMD took steps to address these weaknesses.

Our second Y2K audit concentrated on oversight of the Y2K process within the Department. Although each of the components within the Department is primarily responsible for its own Y2K fixes, JMD monitors and reports on the status of the Department's mission-critical computer systems. Our audit disclosed that the Department had not consistently established how many systems it had to fix, the cost, and their status. Specifically, we found:

JMD has taken steps to address weaknesses that relate to monitoring and reporting the status of its mission-critical computer system. However, JMD maintains that it has little direct oversight responsibility and that the components are ultimately responsible for ensuring that their mission-critical systems are Y2K compliant. Although we agree that primary responsibility resides with the components, we also conclude that JMD's view deprives the Department of the additional safeguards that are desirable if the Department is to meet the Y2K challenge successfully.

USDOJ/OIG - Semiannual Report to Congress, October 1, 1998 - March 31, 1999 |

Page 24 |

Significant Audit Products

Department Financial Statement Audits

The Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990 and the Government Management Reform Act of 1994 require financial statement audits of the Department. Audit oversees and issues the reports based on the work performed by independent public accountants. During this reporting period, we issued the audit report for the Department of Justice Annual Financial Statement for FY 1998. For the third year, the Department received a disclaimer of opinion on the consolidated financial statements. The auditors were unable to obtain sufficient evidence about certain account balances and disclosures.

USDOJ/OIG - Semiannual Report to Congress, October 1, 1998 - March 31, 1999 |

Page 25 |

Significant Audit Products

unable to rely upon the FY 1998 beginning balances, they were unable to determine whether amounts reported in the components' FY 1998 statements of net costs, changes in net position, budgetary resources, and financing were fairly stated.

The following table depicts the audit results for the Department consolidated audit as well as for the nine individual component audits for FY 1998. The Department has made progress toward an unqualified opinion, although improvements are still needed in certain areas.

| Comparison of FY 1998 Audit Results | |||||

| Reporting Entity | Balance Sheet | Statement of Net Costs |

Statement of Changes in Net Position | Statement of Budgetary Resources | Statement of Financing |

| Consolidated Department of Justice | D | D | D | D | D |

| Assets Forfeiture Fund and Seized Asset Deposit Fund | D | D | D | D | D |

| Drug Enforcement Administration | U | D | D | D | D |

| Federal Bureau of Investigation | U | U | U | U | U |

| Federal Prison System | Q | Q | Q | Q | Q |

| Immigration and Naturalization Service | D | D | D | D | D |

| Offices, Boards, and Divisions | D | D | D | D | D |

| Office of Justice Programs | U | D | D | D | D |

| U.S. Marshals Service | D | D | D | D | D |

| Working Capital Fund | U | U | U | U | U |

| D - Disclaimer of Opinion Q - Qualified Opinion U - Unqualified Opinion |

|||||

JABS' Computer Security Controls

The Joint Automated Booking System (JABS) was designed to test an automated booking process that provides for the collection, storage, and retrieval of offender-related data. The system is jointly operated and used by the Department's law enforcement agencies. In our last Semiannual Report to Congress, we reported that JABS did not undergo a cost-benefit analysis and that security weaknesses and compatibility issues existed.

USDOJ/OIG - Semiannual Report to Congress, October 1, 1998 - March 31, 1999 |

Page 26 |

Significant Audit Products

This second audit focused on JABS' computer security. Over the past 10 years, the Department and the OIG have identified and reported computer security as a material weakness for various Department components. For FY 1997, the Attorney General reported computer security to the President as a material weakness and made the improvement of information technology security a high priority.

We found that computer security controls, including password management and intruder lockout protection, were not in place to protect the system and its sensitive data from unauthorized use, loss, or modification. We recommended that JMD adhere to and monitor compliance with existing policy and develop and implement new policy to address the weaknesses.

INS' Selection of Advanced Card Technology

One of INS' functions is to ensure appropriate documentation of aliens at points of entry and to determine the admissibility of persons seeking entry into the United States. INS is also responsible for adjusting the status of and providing other benefits to legally eligible non-citizens.

In FY 1998, in response to mandates established by the Illegal Immigration Reform and Responsibility Act of 1996, INS began using optical stripe technology in producing its Border Crossing Cards and Permanent Resident Alien Cards. Optical stripe technology is capable of holding a biometric identifier such as fingerprints.

We found optical stripe technology to be an expensive alternative compared to two-dimensional bar code technology. Based on an average annual production of 3.1 million cards, we estimate that optical stripe technology costs about $10 million more annually when compared to other available technologies. We recommended that INS justify its technology selection based on current and future security and performance requirements.

FBI Fingerprint and Biographical Check Services to INS

Individuals applying for benefits from INS must furnish fingerprints, biographic data, and other background information to INS. INS requests background checks from the FBI, Central Intelligence Agency, State Department, and Defense Investigative Service depending on the benefit type and the status of the applicants and petitioners at the time of application. FBI background checks include fingerprint and biographical checks.

For FY 1996, INS paid the FBI $32.5 million to conduct more than 1.8 million fingerprint checks and $5.7 million to conduct approximately 1.6 million name checks. In FY 1997, INS paid the FBI $45.5 million for 2.6 million fingerprint checks. INS requested that we conduct an audit of the adequacy of INS practices and procedures for requesting and paying for fingerprint and name checks and the extent and accuracy of FBI billings for the requested services.

We found that INS did not reconcile payments against its requests for fingerprint and name checks conducted by the FBI. INS did not have a system to track and account for all of the fingerprint and biographical check requests submitted to, or the results received

USDOJ/OIG - Semiannual Report to Congress, October 1, 1998 - March 31, 1999 |

Page 27 |

Significant Audit Products

from, the FBI. Because of this weakness, INS paid about $7 million during FYs 1996 and 1997 for unclassifiable and duplicate fingerprint cards, submitted incomplete or inaccurate fingerprint checks for thousands of INS applicants, and did not detect a potential FBI underbilling of approximately $800,000. For name checks, we identified approximately $220,000 that INS incurred unnecessarily for duplicate requests. We also identified more than $230,000 for services rendered by the FBI but not charged to INS. This latter amount is offset by about $563,000 in charges not supported adequately by the FBI. Both INS and the FBI initiated actions to track requests for fingerprint and background check services and to reconcile billings.

Sale and Leaseback of Detention Facilities

The Attorney General has identified lack of detention space as one of the top 10 management issues of the Department. Due to the lack of available detention space, USMS, BOP, and INS rely on state and local governments and private prison contractors to house federal prisoners. About 10 percent of the detention space is provided by private facilities.

We found that private prison contractors have begun selling some of their facilities to real estate investment trusts (REITs) and subsequently leasing the facilities back from the REITs. This arrangement has led to higher rental costs to the federal government, in violation of Federal Acquisition Regulations. For example, we identified more than $1 million in excessive rental charges at the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) facility in Laredo, Texas. We recommended that INS disallow these costs and that USMS, BOP, and INS disallow rental charges above those they would have incurred prior to the sale and leaseback when negotiating contracts in the future. USMS, BOP, and INS concurred with our recommendations.

INS' Timeliness In Inspecting Passengers Arriving at U.S. Airports

In 1990, Congress enacted legislation requiring INS to inspect airline passengers within 45 minutes and annually report its success rate at meeting the time standard. Approximately 52 million immigration inspections in FY 1996 and 62 million in FY 1997 were subject to the standard.

We found that INS had been measuring inspection processing times since shortly after enactment of the 45-minute standard; however, INS had been measuring the time it takes inspectors to inspect an entire flight rather than the time it takes an individual passenger to complete an inspection. We developed a methodology to correctly measure passenger inspections and enable INS to have the necessary performance data readily available to monitor inspection timeliness on an overall, airport-specific, terminal-specific, or inspection-type basis throughout the year.

Using our methodology to measure inspection timeliness, we determined that, of the passengers subject to the 45-minute standard, 96 percent at sampled airports were inspected within this time limit. INS was working with the U.S. Customs Service (Treasury) and the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (Agriculture) to improve the timeliness

USDOJ/OIG - Semiannual Report to Congress, October 1, 1998 - March 31, 1999 |

Page 28 |

Significant Audit Products

of combined federal inspection services. We recommended that INS better coordinate with these agencies to extend the 45-minute time goal to all passengers and to all inspection agencies and coordinate with airlines to better measure processing times. We also recommended that care be taken to prevent the compromise of law enforcement in favor of timeliness. INS concurred with all of our recommendations and agreed to adopt the OIG-developed methodology for measuring timeliness of inspections.

Adjudications and Naturalization Data in INS' Performance Analysis System

INS uses its computer-based Performance Analysis System (PAS) to track and report agency productivity. PAS contains data about the workload activities of INS employees, such as the number of hours worked that relate to the processing of applications for various benefits available under U.S. immigration law. PAS is an important system used to support budget requests, determine position allocations, measure planned versus actual accomplishments, and analyze application backlogs.

Our audit disclosed that PAS adjudications and naturalization data are not reliable. We found arithmetical errors, data omissions, and incorrect posting of data. PAS adjudications and naturalization data are unreliable because (1) monitoring of data collection, consolidation, and reporting at field offices is inadequate, (2) guidance is unclear, and (3) no audit trail exists connecting PAS data to underlying applications and case files. Because the PAS adjudications and naturalization data are unreliable, we concluded that they do not provide INS with an adequate basis for sound decisions and we consider the accuracy of any reports based on them to be questionable.

We recommended that INS (1) require supervisory review of source documents before adjudications and naturalization data are entered into PAS and require periodic inventories to validate the number of pending cases reported in PAS, (2) provide comprehensive, up-to-date guidance and training for the collection, consolidation, and reporting of PAS adjudications and naturalization data, and (3) develop and implement a reliable automated system for collecting, consolidating, and reporting PAS adjudications and naturalization data. Such a system should be compatible with the case management system and incorporate an audit trail permitting the tracing of PAS data to individual applications. INS concurred with our recommendations.

USMS Contracts With CCA

USMS enters into contracts with CCA to provide prison facilities and services for federal prisoners. Our audit of a contract proposal and interim letter of agreement between USMS and CCA for detention services at its Leavenworth, Kansas, facility resulted in USMS' recovery of more than $2 million in questioned costs and the negotiation of a contract that will result in additional savings of more than $11 million over the 5-year life of the contract.

USDOJ/OIG - Semiannual Report to Congress, October 1, 1998 - March 31, 1999 |

Page 29 |

Significant Audit Products

Trustee Audits

Audit conducts performance audits of panel trustees under a reimbursable agreement with EOUST. Individual members of a panel of private trustees are selected and supervised by individual U.S. Trustees. The panel trustees are appointed to collect, liquidate, and distribute personal and business cases under Chapter 7 of Title 11 of the Bankruptcy Code. As a representative of the bankruptcy estate, the panel trustee serves as a fiduciary, protecting the interests of all estate beneficiaries, including both creditors and debtors.

In addition to the statutory requirement to file a final account of the administration of the estate with the court, the panel trustee must provide to the U.S. Trustee an interim report at least every six months for bankruptcy cases with assets. Our audits include determinations of whether the interim reports are complete and accurate and the panel trustee has maintained sufficient management controls over estate assets. Additionally, we review the panel trustees' banking and accounting practices and test accounting transactions. During this reporting period, we issued 78 reports detailing the results of our performance audits of panel trustees.

Our reports are issued to EOUST and include findings such as the failure of the panel trustees to deposit money in a timely manner, invest estate funds properly, and document support for all sales and disbursements. Although the frequency of such occurrences is declining, our reports continue to disclose disbursements that were not properly authorized and sales that were made without obtaining a court order. Another frequently reported deficiency is trustees' failure to adhere to EOUST guidelines for reporting assets and related transactions.

Single Audit Act

The Single Audit Act requires recipients of federal funds to arrange for audits of their activities. Federal agencies that provide awards must review these audits to determine whether prompt and appropriate corrective action has been taken in response to audit findings.

During this reporting period, Audit reviewed and transmitted to OJP 59 reports encompassing 256 Department contracts, grants, and other agreements totaling $512 million. These audits report on financial activities, compliance with applicable laws, and the adequacy of recipients' management controls over federal expenditures.

OMB Circular A-50

OMB Circular A-50, Audit Follow-Up, requires audit reports to be resolved within six months of the audit report issuance date. The status of open audit reports is continuously monitored to track the audit resolution and closure process. As of March 31, 1999, the OIG had closed 273 audit reports and was monitoring the resolution process of 297 open audit reports.

USDOJ/OIG - Semiannual Report to Congress, October 1, 1998 - March 31, 1999 |

Page 30 |

Audits Over Six Months Old Without Management Decisions or in Disagreement

As of March 31, 1999, the following audits had no management decision or were in disagreement:

Audit Resolution Committee

Department of Justice Order 2900.6A establishes an Audit Resolution Committee (ARC) to resolve significant disagreements between the OIG and the audited component regarding audit findings and recommendations or corrective actions taken. If agreement cannot be reached after every reasonable effort to resolve an audit report has been made, Order 2900.6A provides that the issues should be referred to ARC. The Deputy Attorney General chairs ARC and has responsibility for resolving disputed findings and recommended corrective actions.

During this reporting period, JMD initiated a referral to ARC regarding a series of OIG audits dealing with intergovernmental agreements under which USMS paid state and local entities to hold federal prisoners in their jails. The audits concluded that USMS had been overcharged for interest and profit expenses in excess of $5 million. JMD argued that these costs were not prohibited and should not be questioned, based upon its interpretation of OMB Circular A-87. Both USMS and the OIG contended that the interest costs charged

USDOJ/OIG - Semiannual Report to Congress, October 1, 1998 - March 31, 1999 |

Page 31 |

Other Activities

to USMS were not allowable under Circular A-87 and had been expressly prohibited by USMS instructions to state and local entities and pointed out that USMS had already undertaken efforts to recover the questioned costs. With respect to profit, USMS has not approved the payment of profit in the past and did not dispute the OIG finding in the audit at issue but sought to be allowed to pay profit in future exigent circumstances. The matter remains pending before ARC.

| Audit Reports | Number of Audit Reports | Enhanced Revenues |

| No management decision made by beginning of period | 3 | $21,589 |

| Issued during period | 3 | $141,915 |

| Needing management decision during period | 6 | $163,504 |

| Management decision made during

period: --Number management agreed with |

4 |

$162,526 |

| No management decision at end of period | 2 | $978 |

USDOJ/OIG - Semiannual Report to Congress, October 1, 1998 - March 31, 1999 |

Page 32 |

Audit Statistics

Funds Recommended to be Put to Better Use |

||

| Audit Reports | Number of Audit Reports | Funds Recommended to be Put to Better Use |

| No management decision made by beginning of period | 32 | $32,000,242 |

| Issued during period | 12 | $16,085,654 |

| Needing management decision during period | 44 | $48,085,896 |

| Management decision made during

period: --Amounts management agreed to recover (disallowed) --Amounts management did not agree to recover |

39 1 |

$41,977,365 $127,974 |

| No management decision at end of period | 30 | $5,980,557 |

| Audits With Questioned Costs | |||

| Audit Reports | Number of Audit Reports | Total Questioned Costs (Including unsupported costs) | Unsupported Costs |

| No management decision made by beginning of period | 73 | $48,228,184 | $6,100,960 |

| Issued during period | 41 | $14,932,260 | $7,404,333 |

| Needing management decision during period | 114 | $63,160,444 | $13,505,293 |

| Management decision made during

period: --Amounts management agreed to recover (disallowed) --Amounts management did not agree to recover |

83 1 |

$34,765,585 $114,681 |

$8,508,673 |

| No management decision at end of period | 30 | $28,280,178 | $4,996,620 |

USDOJ/OIG - Semiannual Report to Congress, October 1, 1998 - March 31, 1999 |

Page 33 |

Audit Statistics

| Audits Involving Recommendations for Management Improvements | ||

| Audit Reports | Number of Audit Reports | Total Number of Management Improvements Recommended |

| No management decision made by beginning of period | 126 | 423 |

| Issued during period | 73 | 348 |

| Needing management decision during period | 199 | 771 |

| Management decision made during

period: --Amounts management agreed to recover (disallowed) --Amounts management did not agree to recover |

1471 5 |

599 12 |

| No management decision at end of period | 50 | 160 |

| 1 This includes three audit reports that were not resolved during this reporting period. However, management has agreed to implement a number of, but not all, recommended management improvements in these audits. | ||