Two Department of Justice (DOJ) components have key roles in the detention of federal detainees – the Office of the Federal Detention Trustee (OFDT) and the United States Marshals Service (USMS). The OFDT manages DOJ’s detention resource allocations, and coordinates DOJ’s detention activities with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).1 The USMS is responsible for housing and transporting federal detainees from the time they are brought into federal custody until they are either acquitted or incarcerated.2

As shown in the following graph, due to the severe shortage of federally owned detention space, the USMS heavily depends on state and local governments to provide detention space and services:

Type of Facility

[Image Not Available Electronically]

Source: OFDT

To meet its need for detention space, the USMS has entered into Intergovernmental Agreements (IGA) with an increasing number of state and local detention facilities. IGAs are formal agreements between the USMS and a state or local government in which the state or local government agrees to house federal detainees at an agreed-upon daily rate (a “jail-day rate”). As of February 2006, the USMS had approximately 1,600 active IGAs with state and local governments to rent jail space. In fiscal year (FY) 2005, DOJ spent $750 million of its $1 billion detention budget on IGAs.

In our judgment, given the rising federal detainee population and increasing expense of housing federal detainees, it is critically important that the USMS has a system in place to ensure that it obtains needed detention space without overpaying for it.

Funding Detention Growth

A significant challenge presented by rising detention populations is DOJ’s ability to obtain affordable bed space for individuals housed in non-federal facilities. The cost of detention has been rising rapidly, and during FYs 2003 – 2005 the funds budgeted for the detention of federal detainees fell short of the amount needed to fully fund detention activities. DOJ officials attributed the shortfalls to significantly inaccurate budget projections by the USMS and OFDT. According to these officials, new law enforcement initiatives, policies, and laws caused an increased number of arrests, which exceeded the forecasts used to calculate budget requests.

According to the OFDT, its efforts to reduce detention costs have focused on decreasing the amount of time individuals spend in detention after sentencing while awaiting transfer to the BOP. However, we believe that the OFDT and USMS could realize significant additional cost savings if they addressed deficiencies in how prices are set in individual IGAs established with state and local law enforcement agencies for detention bed space.

Audit Approach

The objective of the audit was to determine if the USMS and OFDT employed an effective monitoring and oversight process for IGAs. Appendix I contains more information on our objective, scope, and methodology.

Our report contains three main findings. The first discusses a disagreement between the OFDT and the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) regarding the recoverability of overpayments identified in past OIG audits. The second finding concerns the OFDT’s revamping of IGA pricing through an econometric statistical pricing model. The third finding discusses needed improvements in the policies and procedures, training, and defining responsibilities for establishing and monitoring IGAs.

First Finding: Dispute Over Detention Space Overpayments

Since 1995, the OIG has audited 31 individual IGAs between the USMS and state and local governments for detention space. These audits often concluded that the USMS had paid state and local governments significantly more than the actual and allowable costs for this space. In total, the OIG reported dollar-related findings of almost $60 million from these 31 IGA audits. The following are examples of findings from three of these audits:

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED]. Our audit revealed that the [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] Sheriff’s Office was not required to prepare a cost sheet to support its jail-day rate.3 Further, the audit concluded that [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] Sheriff’s Office had costs to support a jail-day rate that was about $17 less per day than the rate paid, resulting in overpayments of almost $1.8 million during calendar years 2000 and 2001.

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED]. Our audit concluded that the [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] Jail’s FY 2003 allowable costs supported a jail-day rate of $30.62, resulting in overpayments of more than $2.8 million during FYs 2003 and 2004.

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED]. Our review of the costs and inmate population listed on the cost sheet supported a $52.26 jail-day rate, while the USMS paid the [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] Jail $65 per jail day, resulting in overpayments totaling almost $2.9 million for FYs 2004 and 2005.

However, on March 17, 2006, the OFDT advised the USMS to refrain from seeking reimbursement of overpayments identified in OIG audits of individual IGAs.4 As discussed below, the OFDT reasoned that because, in its view, the audited IGAs were negotiated fixed-price contracts not based solely on costs, the USMS could not recoup these overpayments. In contrast, the OIG believes that actual and allowable costs formed the basis for the jail-day rates contained in the agreements, and that even if the IGAs are fixed-price agreements as the OFDT contends, it may still be appropriate to recover overpayments, based on the circumstances of each case. Accordingly, the OIG believes that the DOJ should individually address each of the OIG’s prior audits to determine if action on the payments above cost is appropriate.

Negotiated Fixed-Price Contracts (OFDT Position)

According to the OFDT’s argument, the IGAs at issue were fixed price agreements that were not specifically limited to the repayment of actual costs incurred by the contracting state or local government. The OFDT believes that although cost data provided by a state or local government was one factor used in reaching the agreed-upon jail-day rate, the USMS ultimately agreed to a fixed rate and cannot now seek to recover any payments it may have made above costs.

To support this conclusion, the OFDT points to a December 2002 legal opinion from the DOJ’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC). This opinion concluded that Section 119 of Public Law 106-553 (also known as the 2001 Department of Justice Appropriation Act) confers authority on the Attorney General to enter into fixed price detention agreements. Section 119 provides:

Notwithstanding any other provision of law, including section 4(d) of the Service Contract Act of 1965 (41 U.S.C. 353(d)), the Attorney General hereafter may enter into contracts and other agreements, of any reasonable duration, for detention or incarceration space or facilities, including related services, on any reasonable basis.

The OFDT therefore concluded that the IGAs do not limit state or local governments to the reimbursement of costs only. The OFDT further stated that because the IGAs we audited typically describe the unit price the federal government will pay as a “fixed rate,” and costs were only one factor considered in determining this rate, the overpayments identified by the OIG audits are not recoverable.

As a result, in its March 17, 2006, memorandum the OFDT “advised the USMS to refrain from seeking reimbursement of overpayments” found by the OIG audits. Recently, OFDT obtained an opinion from the General Counsel of the Justice Management Division stating that the IGAs are “fixed price agreements that do not contain a basis for the Department to seek retroactive price adjustment” as a matter of contract law.

Cost-Based Agreements (OIG Position)

The OIG disagrees with the OFDT’s and JMD’s conclusion that the IGAs at issue are fixed-rate agreements based on factors other than cost. We do not dispute that, at least since the passage of Section 119, the USMS has the authority to enter into IGAs based on other factors, and that accordingly profit may be included in the calculation of the IGA rate. However, the OIG does not agree that the USMS exercised its authority to do so for past IGAs, including the 31 that were the subject of the OIG’s audits.5 Indeed, even the OLC opinion on which the OFDT relies describes the IGAs that pre-dated passage of Section 119 as having “typically set compensation for these services at the cost actually incurred by the provider.” In addition, the OIG believes that the term “fixed rate” described the unit price to be paid in IGAs, but that it was calculated based on the state or local government providing an accurate description of its allowable costs. For example, in negotiations for the IGAs the local governments were informed that the rate was based on allowable costs, not any profit, and that the local governments would be held accountable for any overpayment or audit disallowance. As we describe below, support for our view is found in: (1) the language of the agreements, (2) a memorandum, dated August 1, 2002, from the prior Detention Trustee, and (3) the USMS’ own past practice.

Language of the Agreements

The cost sheet instructions that were given to state and local governments when they sought the IGAs defined an IGA as a formal written agreement between the USMS and a state or local government to house federal detainees at a jail-day rate based on actual and allowable costs for the same level of service provided to state or local prisoners in a specific facility. The cost sheet instructions also informed the preparer of the following:

A jail-day rate will be computed on the basis of actual and allowable costs associated with the operation of the facility that benefit federal detainees during the most recent accounting period.6

“Local Governments shall only request the reimbursement of costs to the extent provided for in the latest revision of OMB Circular No. A-87.”7

The cost sheet also contained a certification statement that the Comptroller or Chief Financial Officer of the local government was required to sign attesting to the fact that the cost sheet does not include any costs prohibited by the Circular. According to the cost sheet instructions, Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Circular A-87 is the criteria used by the USMS in evaluating whether IGA costs are allowable.

The USMS IGA Manual states that an IGA analyst at USMS headquarters is supposed to review the cost sheet for cost allowability and the accuracy of capacity and average daily population figures. Based on the cost sheet information, the IGA analyst then calculated a jail-day rate using the following formula:

| Jail-Day Rate Calculation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

256 |

365 |

93,440 |

||

X |

= |

|||

Average Daily Population |

Days Per Year |

Jail-Days |

||

$5,088,716 |

93,440 |

$54.46 |

||

÷ |

= |

|||

Total Operating Cost |

Jail Days |

Jail-Day Rate |

||

| Source: USMS IGA Manual |

As detailed in the table, a facility with an average daily population of 256 would equate to 93,440 annual jail days. If the facility’s total annual operating costs were $5,088,716, this amount would be divided by the 93,440 annual jail days to arrive at a jail-day rate of $54.46. In this example, the USMS would pay the state or local facility $54.46 to house one of its federal detainees for one day.8

The IGA Manual also states that t he USMS IGA analyst will then discuss the jail-day rate with the appropriate local official, and prepare a Record of Negotiation documenting the rationale for the jail-day rate. The IGAs state that the local governments are responsible for complying with OMB Circular A-87, and inform the local governments that they will be held accountable for any overpayment, audit disallowance, or breach of the agreement that results in a debt owed to the federal government.

Prior Detention Trustee Memorandum

In a memorandum to the Deputy Attorney General dated August 1, 2002, the prior Detention Trustee agreed with our position.9 The prior Detention Trustee noted that most if not all IGAs limited reimbursement to actual costs or to the same daily costs that state and local authorities incur to hold their own prisoners. Further, these IGAs did not allow for a payment of profit to state and local governments. Accordingly, the prior Detention Trustee concluded:

[T]he issue of whether the Department may or may not pay a profit or fee should not be a contentious item in these audits, since the audits were conducted on IGAs where both the departmental components and the state or local governmental entity agreed to reimbursement of actual costs.

The prior Detention Trustee therefore drafted a policy that required the USMS to submit written justification to the OFDT and obtain its written approval prior to entering into fixed-price IGAs based on factors other than cost under Section 119. During our audits of the 31 IGAs, we did not identify any justifications or prior written approvals by the Detention Trustee that fixed-price detention services were acquired.

USMS Past Practice

We also noted that from 1997 to 2005 the USMS IGA Audit Branch performed its audits in the same manner as the OIG (that is, to determine if IGA jail-day rates were based on actual and allowable costs). For example, in a January 1998 audit of the [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] Jail in [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED], the USMS IGA Audit Branch determined that a $65 temporary jail-day rate was not supported and that the operating costs only supported a $37.95 jail-day rate. The USMS Audit Branch recommended that the USMS “negotiate a revised jail-day rate based on the information contained in this report and actual cost and prisoner population data” and “remedy the $3,883,433 in questioned costs.” Similarly, in an October 1999 audit of the [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] City Jail, the USMS IGA Audit Branch reported that the supportable jail-day rate was $4.22 less per prisoner than the rate that was in effect and concluded that the USMS had incurred $127,874 in additional costs during FY 1998. Although no recommendations were developed, the report stated that the information was provided for use in any future rate negotiations and any collection efforts deemed appropriate.10

In addition, we noted that the USMS has recovered overpayments identified in previous OIG audit reports. For example, the USMS recovered $156,000 in overpayments from the [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] Sheriff’s Office over an extended period – September 2000 through August 2004 – by reducing the jail-day rate of $32.97 by $1.17, until the $156,963 in overpayments was recouped. Similarly, as a result of our audit report on the USMS’s IGA with [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED], the USMS negotiated a 5-year repayment schedule over which the jail repaid over $1 million. In addition, the USMS negotiated a reduced future rate.

Resolution of Remaining OIG Open Audits

As discussed above, the OFDT believes that the IGAs at issue are fixed-rate contracts and that, accordingly, there is no basis in the agreements to force the audited facilities to repay the overpayments identified by the OIG. The OFDT therefore instructed the USMS not to seek to recover these overpayments. However, the OIG believes that even if one accepts the OFDT’s argument, its instruction not to seek the recovery of any overpayment was overbroad and incorrect. Rather, we believe that the USMS should address each audit individually and should remedy the questioned costs identified by the OIG by either collecting overpaid funds; providing documentation to support the existing IGA rate; adjusting the IGA rate and offsetting future payments over a reasonable time; or administratively waiving the questioned costs on a case-by-case basis, based on the inability to collect the funds or other exigencies such as a lack of other viable location, security problems, or significantly greater costs that would result from changing facilities. In addition, the USMS should consider whether, based on the audit findings, jail-day rates should be reduced prospectively.

Second Finding: Revamping the IGA Process

Although this dispute over past IGAs remains unresolved, the OFDT is now in the process of revising how IGA rates are calculated on the basis of “price reasonableness” rather than costs. We describe in this section the OFDT’s new IGA process, called eIGA.

In April 2005, the OFDT formed an interagency working group to review the costs associated with the use of state and local detention facilities, and to standardize the process of entering into IGAs in an attempt to ensure that the jail-day rates paid by the federal government were fixed, fair, and reasonable, and would no longer be subject to adjustments based on the actual costs of providing the service. According to the OFDT, fixing the price for detention services would also “flatten out” budget predictions by locking in rate adjustments at a set time, and would provide incentives for jails to control costs. As a result of the working group’s efforts, the OFDT has been pursuing changes to the IGA process by developing what it calls the eIGA system.

According to the OFDT, eIGA is an attempt to “e-gov” the IGA application process.11 The OFDT stated that it believes that eIGA will improve the process of establishing IGAs by providing an automated system that establishes [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] pricing for detention space and services provided by state and local facilities. The core of eIGA is an econometric statistical pricing model for determining a fixed-price [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED]. The model starts with a [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] core jail-day rate that was calculated using December 2003 IGA rates.12 That core rate is adjusted based on various factors to arrive at an adjusted core rate (also known as the “should cost” rate). The adjusted core rate is provided to the USMS analyst, with [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED], as shown in the following screen shot:

Screen Shot of Rate Comparison13

Source: OFDT

According to the OFDT, once eIGA is operational, detention facilities will electronically apply for an IGA by completing a short application that describes the facility’s capacity and staffing, jail operating expense information, services to be provided, oversight and accreditations, health care policies, and a proposed IGA rate.

A major change in this new approach is that unlike cost sheet data that has been used historically to compute jail-day rates, jail-day rates established using eIGA will not be based on a detention facility’s cost information. Rather, the award will be determined by “price reasonableness,” which will be calculated by comparing a detention facility’s proposed rate to the adjusted core rate [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] generated by the eIGA model and the established rates of similar facilities.

According to OFDT, cost sheet data was not always reliable and did not address whether a price paid in a geographical area was reasonable compared to other facilities. For example, OFDT noted that some facility administrators may pay salaries to individual employees in excess of the norm for the facility, the county, or salaries generally paid in the correctional field for such positions.14 Under the process historically used to establish IGAs, the actual cost of the salaries, even if they are unreasonable in comparison to other county or correctional salaries in the regional area, would be allowable on an IGA.

In addition, according to the OFDT, under the eIGA process, if a jail proposes a rate that far exceeds the adjusted core rate and the rate of similar facilities, a USMS IGA analyst could “drill down” into the jail operating expense information and compare salaries or overtime usage to that of similar local facilities to determine the possible causes for the excessive proposed rate. The OFDT believes that comparing proposed rates to the rates of similar facilities will promote cost efficiencies.

Under eIGA, although the USMS will negotiate jail-day rates with individual jails, OFDT will review and approve each jail-day rate before any rate is finalized. The OFDT intends for a complete record of the negotiation, including a market comparison of jail rates and life cycle of each IGA, to be documented in eIGA instead of the USMS’s current paper files.

In addition, according to OFDT, jail-day rates established through eIGA will be fixed for 36 months. Historically, jails were allowed to seek increases to the jail-day rate after 1 year. Therefore, under eIGA jails will have an incentive to control costs because they will not be allowed to request a rate increase prior to 36 months unless there were major operational changes with respect the USMS’s use of the jail. After 36 months, a jail seeking a rate increase would have to reapply through eIGA.

OIG Concerns with eIGA

According to the OFDT, the primary benefit of using the new process is that an IGA analyst can compare the proposed and adjusted core rates to the rates of similar facilities. The OFDT stated that in determining what is a similar facility, emphasis will be placed on the relationship of a jail’s expense information to that of other jails in the area (or within the state) that have a similar population, security level, size, staffing, and correctional programs offered. Additionally, when appropriate, a comparison to private and federal jail-day rates will be performed.

We believe that the eIGA concept is a positive step to improving the process historically used to establish jail-day rates. As discussed further in Finding III of this report, we identified significant deficiencies with how jail-day rates were established and monitored in the past. However, because eIGA is not yet operational, we were unable to test how jail-day rates will be established using eIGA. In addition, the OFDT has not issued guidance on how jail-day rates will be established using eIGA. According to OFDT, it intends to develop a 16-hour training course and handbook on how to use the system and perform a price analysis. As a result of these factors, it is difficult to predict how successful eIGA will be once it is operational.

During the course of this audit, the OIG had expressed concern that the OFDT’s initial eIGA plan not to require state and local jails to submit detailed cost information constituted a serious flaw in the OFDT’s revised process.15 As a result of our concerns, and to adequately address the applicability of the Service Contract Act, the OFDT added the jail operating expense information to eIGA.16 With the addition of the jail operating expense information, eIGA captures many cost sheet categories including salaries and benefits, consultant and contract services, medical care and treatment, facility and office, safety and sanitation, and insurance. However, eIGA does not capture a jail’s average daily population, indirect costs, or revenue generated from a detention facility’s operation (also known as credits).

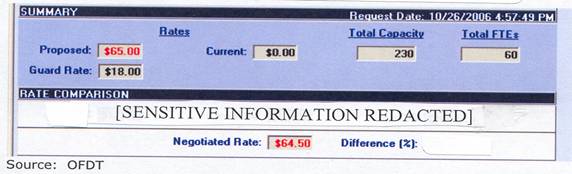

We believe that the OFDT can improve eIGA to ensure that the USMS is negotiating the best possible jail-day rates that will help control rising detention costs by modifying the jail operating expense information to capture a jail’s average daily population, indirect costs, and credits. In turn, this information should be used to calculate a jail-day rate, based on costs, that is presented to the IGA analysts as an additional field in the following summary screen shot:

Summary Screen Shot of Negotiated Rate

The OFDT stated that these will not be cost-based agreements, and that cost and average daily population data change daily. As discussed in Finding I, we recognize that OFDT and USMS may negotiate fixed–price IGAs not based on costs. However, we believe the true measure of eIGA’s success will be to compare the rates negotiated through eIGA to a detention facility’s actual and allowable costs. Presenting the information captured in the jail operating expense information portion of eIGA as a single rate will give the USMS more evidence and leverage in its negotiations, and will help ensure that negotiated jail-day rates are fair and reasonable. Presenting this data is not difficult, can assist in reducing the jail-day rate paid by the USMS, and could provide an important check on the price reasonableness model as demonstrated in our review of jail-day rates that were established using the eIGA pilot program.

In addition, as shown by the above screen shot, the [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED]. A detention facility potentially could earn [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED]. This is possible because detention facilities could [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED].

Piloting the Model for Establishing IGAs

In September 2005, the OFDT and USMS began using the new eIGA pricing model as part of a pilot process for awarding IGAs. However, because the eIGA system is not operational, jails have continued applying for jail-day rates using cost sheets, and the USMS has requested from OFDT an adjusted core rate, similar to the eIGA rate, that is calculated manually for each facility.

USMS IGA analysts then determined price reasonableness by comparing a requesting jail’s proposed rate to the adjusted core rate provided by OFDT. Although USMS IGA analysts could have used the cost sheets submitted by the jails as part of their analysis in determining price reasonableness, we found that a cost sheet analysis by the USMS was not always performed. Further, unlike the planned process for eIGA, a comparison of proposed rates to similar facilities was not performed during the pilot. The USMS has also continued to use the standard IGA language it has used for years (that jail-day rates are established based on actual and allowable costs associated with operating the facility).

As of June 2006, the OFDT and USMS had used the model to award approximately 90 IGAs as part of a pilot project. We judgmentally selected 11 of the 90 IGAs awarded and reviewed detailed documentation from OFDT and the USMS to determine how the awarded rates compared to the cost-based rate previously used in awarding IGAs. The following table shows our results on how the awarded rate compared to the cost sheet rate, the adjusted core rate, and the [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED]:

Sampled IGAs Awarded Using the Model17

| Facility Name | Requested Rate | Cost Sheet Rate18 | [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] | [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] | [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] | Awarded Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

||||||

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$64.32 |

$64.32 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$64.32 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$88.25 |

$85.52 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$85.52 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$75.00 |

$79.67 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$70.00 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$78.06 |

$68.46 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$65.00 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

||||||

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$80.00 |

$76.68 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$80.00 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$61.42 |

$54.13 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$54.13 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$60.46 |

$56.28 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$51.16 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$50.00 |

$38.22 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$45.00 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

||||||

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$85.00 |

$102.12 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$82.00 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$53.00 |

$54.28 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$44.97 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$77.34 |

$77.55 |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] |

$86.00 |

| Source: OFDT and USMS |

Although eIGA will collect a jail’s cost information that will be used in analyzing the proposed jail-day rate, the OFDT does not plan on presenting this information to the IGA analysts as a single rate for comparison to the proposed rate, adjusted core rate, and the rates of similar facilities. Our review, however, revealed the benefits of presenting the cost information as a rate to help establish a reasonable jail-day rate.

- [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] - The USMS IGA analyst used the cost sheet as the basis for negotiations with the Center. The cost sheet supported a jail-day rate of $54.13, which was the rate offered to and accepted by the Center. The rate [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] the OFDT provided adjusted core rate of [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED]. The Center had originally requested a jail-day rate of $61.42, which [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] the adjusted core rate. However, the cost sheet provided by the Center only supported a rate of $54.13. Using this cost information, the USMS negotiated that rate. Without cost information, the USMS may have accepted the original rate of $61.42 as reasonable, based on the eIGA model, at an extra estimated cost to the taxpayer of almost $270,000 per year.

However, it was not clear to us whether the USMS always analyzed cost sheets or considered in negotiations for the jail-day rate both the cost and the model-generated rate, as shown in the following example:

- [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] - The USMS IGA analyst offered the [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] $45 because it “[SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] ‘should cost’ rate.” There was no indication in the file that the IGA analyst reviewed the cost sheet. Our review of the cost sheet revealed that allowable costs only supported a rate of $41.64. In addition, the [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] represented on the cost sheet that its average daily population was 660 inmates. However, we noted that [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] presents an average daily jail population on its web site of 719. If the average daily population of 719 was used to calculate a jail-day rate, the jail-day rate would be $38.22, or 15 percent lower than the $45 jail-day rate that was awarded, resulting in possible additional costs to the USMS of about $148,000 per year.

Third Finding: Improvements Needed in IGA Oversight

As part of our audit, we also reviewed 34 additional IGAs that were utilized by the USMS in establishing jail-day rates prior to the piloting of the eIGA model. For each selected IGA, we reviewed cost sheets, records of negotiations, and available cost and average daily population data utilized by the USMS in establishing jail-day rates. For the IGAs we sampled, we found that USMS IGA analysts generally reviewed cost sheets and documented their analysis of the costs in establishing jail-day rates. Additionally, the USMS IGA Audit Branch sometimes performed detailed pre-award reviews of the detention center’s costs that were used by the USMS IGA analysts to establish jail-day rates based on actual and allowable costs. For example, the [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] submitted a cost sheet to the USMS on March 1, 2000, based on FY 1999 costs, requesting a rate of $103.27. The USMS conducted an audit of the cost sheet and developed an audited rate of $84.39, which the USMS used in the IGA awarded to [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] in September 2000.

The USMS pre-award audits also allowed the USMS to identify unallowable costs and establish jail-day rates based on actual and allowable costs. However, according to the USMS, a pre-award audit of new IGAs or rate changes to existing IGAs is not always possible due to staffing and budget constraints. But in the absence of pre-award audits, we often found unallowable costs such as transportation salaries and interest; cost sheets that contained cost and average daily population that did not support the requested rate; and understated average daily population numbers.

An example of an IGA that resulted in a jail-day rate that exceeded allowable costs is [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED]. The USMS provided a temporary rate increase to the [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] for $49.84 effective February 1, 2003, pending the results of a planned USMS audit.19 On May 23, 2003, the USMS issued an audit report that supported a lower rate of $40.49. Although a lower rate was recommended, a modification to lower the rate was not implemented until May 2, 2005. According to the IGA Manual, temporary rates can be in effect for up to 12 months pending receipt and review of actual cost data. However, this temporary rate was in effect for 27 months.

USMS officials told us that the lower rate was not immediately implemented because of a backlog of IGA actions. Further, an IGA analyst told us that the modification was not immediately implemented because the U.S. Marshal in this district did not want the lower rate implemented. Based on the USMS’s use of this jail since the effective date of the rate increase, we estimate that the USMS may have paid an additional $590,892 for bed space for FYs 2003 through 2005.

According to USMS officials we interviewed, detention facilities fight for every penny when entering into an IGA, especially if they know there is a limited supply of bed space in their geographical area. Further, a USMS official stated that the USMS competes with ICE and state governments for the same bed space, and that ICE pays more and guarantees the use of its bed space, while the USMS does not. As a result, detention facilities often give priority to ICE detainees. According to the USMS, jail-day rates that exceed allowable costs are occasionally established to appease the local detention officials. Moreover, due to the shortage of federal detention space, the USMS is under pressure to obtain detention space from state or local facilities near federal courthouses. Paying a nearby detention facility a higher rate may appear preferable to the operational and logistical costs of using a more distant but less expensive facility. However, we believe that allowing payment for services to appease a state or local jail keeper will result in similar demands for payment from other localities that in the past agreed to be reimbursed on the basis of actual costs.

We recognize that OFDT is revamping the process for procuring detention space, as described above in the eIGA section. However, we believe that continued improvements are needed in policies and procedures, training, and defining responsibilities for establishing and monitoring IGAs, regardless of the implementation of the new system, for the reasons described below.

Policies and Procedures

The guidance available to the IGA analysts and district personnel for reviewing IGAs include the USMS IGA Manual, the USMS Directives, the instructions that are provided with the cost sheet, OMB Circular A-87, and an OFDT memorandum to the Deputy Attorney General on implementing Section 119, dated August 1, 2002. In our judgment, the OFDT’s and USMS’s policies and procedures must be an integral part of their financial and business practices for awarding and monitoring IGAs. They must contain measures for: (1) protecting resources against waste, fraud, and inefficiency; (2) ensuring accuracy and reliability in financial and operating data; (3) securing compliance with policies; and (4) evaluating performance.

Our review found that the OFDT has not yet issued any policies and procedures related to the new eIGA process. Because the new process involves significant changes from past practices, we believe that the OFDT should issue detailed guidance on awarding IGAs through eIGA before it becomes operational.

Our review also found that the USMS did not always adequately document its decisions for establishing jail-day rates. Without adequate documentation of how a jail-day rate was established, neither the USMS, OFDT, nor the OIG can determine whether the USMS paid a reasonable jail-day rate. For example, the IGA Manual does not address how non-cost factors such as a need to alleviate a critical shortage of jail space in a district should be valued in establishing jail-day rates.

We believe the new policies and procedures should include clear guidance on the following:

how to negotiate with detention facilities;

clearly documenting the basis for negotiated jail-day rates;

evaluating cost and non-cost factors;

when it is appropriate to deviate from the model and how deviations will be documented;

defining, evaluating, and documenting the analysis of established rates of similar facilities in justifying a jail-day rate; and

limitations on profit that should be included in IGAs.

Training

Although IGA analysts collectively commit the USMS to pay state and local detention facilities hundreds of millions of dollars annually, most of the USMS IGA analysts told us their training was not adequate for their level of responsibility. USMS IGA analysts play an important role in ensuring that detention space is obtained at the best jail-day rate possible, and we believe annual training plans should be developed for them to provide appropriate procurement competencies, such as those outlined by the Federal Acquisition Institute (FAI).20

Defining Responsibilities for Establishing and Monitoring IGAs

USMS District personnel and the Programs and Assistance Branch (PAB) at USMS headquarters share responsibility for establishing and monitoring IGAs. We found that the oversight of IGAs by USMS Districts and USMS Headquarters was deficient.

District Responsibilities

The USMS Directives state that each U.S. Marshal will review the cost sheets for completeness and accuracy of information (particularly staffing levels and types of services provided). We interviewed personnel from the USMS districts of Eastern Virginia, Northern Georgia, Western Texas, Nevada, and Western North Carolina, and found that four of these five district offices performed no review of the cost sheets. District officials from Northern Georgia told us that they reviewed cost sheets, but qualified their response by saying that they only review the cost sheets for “obvious errors.”

In addition, we found that none of the five districts performed post-award monitoring of detention center costs or expiration dates. As a result, we queried the USMS’s “Prisoners” database for expired IGAs.21 We identified 451 IGAs that had expiration dates, of which 330 had expired as of January 31, 2006. Of the 330 expired IGAs, we identified 157, 216, and 300 IGAs that were expired as of the end of FY 2003, 2004, and 2005, respectively. We estimated that the USMS made over $175 million in payments on the expired IGAs during FYs 2003 through 2005.

Programs and Assistance Branch Responsibilities

The Programs and Assistance Branch (PAB) is the USMS headquarters section responsible for awarding and overseeing IGAs. Despite the increasing need for detainee bed space, staff reductions in the USMS’s PAB has significantly limited the USMS’s ability to review and follow up on IGA issues. We reviewed PAB staffing reports from 1999 through 2006 and found that authorized staff levels dropped from 11 full-time equivalents (FTEs) with 2 vacancies in 1999 to 6 FTEs with 3 vacancies in 2006. Further, the number of audits performed by the USMS IGA Audit Branch decreased from 29 audits in 2003, to 16 in 2004, to 1 audit in 2005. While the PAB was not the only division to lose FTEs due to USMS budget cut backs, the decline in the number of audits performed by the Audit Branch placed an increasing burden on IGA analysts to identify unallowable costs prior to the establishment of a jail-day rate.

With limited staffing, the PAB had not conducted sufficient post-award IGA monitoring. According to PAB officials, once an IGA is in place, it usually remains in place at the initial jail-day rate until the detention center requests an increase in the rate. As a result, there was no monitoring of IGAs after award, and an IGA could remain in place indefinitely without the USMS knowing if a rate change was warranted. Yet, after an IGA is awarded, conditions may change that warrant a reduction in a jail-day rate. For example, in our audit of the [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED], the original FY 1996 cost sheet was based on an average daily population of 244.22 However, in FY 2004, the average daily population was 877, an increase of 260 percent. This resulted in an audited rate that was $17 less than the rate paid by the USMS, for total unallowable and unsupported costs of over $5 million for 2 years.

Although PAB officials suggested to us that each district is in the best position to monitor IGAs, they also told us that districts may not report issues that could result in the IGA rate decreasing, especially if they believe the issue may result in the cancellation of an IGA. If a detention center cancels an IGA, the USM would have to find a new facility to house detainees, which may be less convenient than the detention center being used. PAB officials told us that the USMS districts do not want to “stir up the pot,” especially if they need the bed space.

We recognize that monitoring IGAs to ensure that the cost and average daily population continue to reflect an appropriate jail-day rate will no longer be an issue if all future IGAs are awarded under the eIGA process. However, districts will continue to play an important role in identifying detention facilities that meet USMS standards and can support the district’s detention requirements. We believe district and PAB responsibilities need clarification on the new process, especially those pertaining to the policies and procedures for establishing rates and monitoring expiration.

Conclusion

Rising detention population and costs presents a challenge to the DOJ’s ability to obtain affordable bed space for individuals not housed in federal facilities. We recognize that there are significant pressures on the USMS to obtain detention space through state and local facilities. However, allowing payment for services that far exceed costs, without adequately analyzing and documenting price reasonableness and cost, could exacerbate the continuing escalation in detention costs nationwide. Because DOJ’s current detention budget exceeds $1 billion, the long-term budget implications of IGA policies are substantial.

The OFDT and USMS are moving away from their past policy of reimbursing state and local jails at a rate based on their allowable costs to a system that will set a fixed jail-day rate that allows for payments to state and locals above their allowable costs. To help in setting the new fixed rates, the OFDT has developed a pricing model that takes into account certain cost variables. The OFDT stated that the primary benefit of using the new process is that an IGA analyst will compare the proposed and adjusted core rates to the rates of similar facilities. We believe that the eIGA concept is a positive step to improving the process previously used to establish jail-day rates. Yet, we believe that OFDT can improve eIGA to ensure that USMS negotiations help control rising detention costs. Although eIGA will capture many of the cost sheet categories, it will not capture a jail’s average daily population, indirect costs, or credits, which are needed to compute a detention facility’s costs. We believe that the OFDT should modify eIGA to capture this information, and present this information to the IGA analysts as a cost-based rate because the true measure of eIGA’s success will be to compare the rates negotiated through eIGA to a detention facility’s actual and allowable costs. Presenting the cost information as a single rate will give the USMS more evidence and leverage in its negotiations, and will help IGA analysts establish fair and reasonable jail-day rates.

Recommendations

As a result of our review, we make 10 recommendations regarding the OFDT’s and the USMS’s oversight of IGAs. The recommendations include addressing each open recommendation from prior OIG audits of IGAs, which collectively contains dollar-related findings of $37 million; modifying eIGA so that it presents a jail-day rate to the IGA analysts based on the actual and allowable costs of the jail; developing guidance and training on how jail-day rates will be established using eIGA; developing guidance that limits the amount of profit a state or local jail can earn for housing federal prisoners; and developing annual training plans for IGA analysts that will provide appropriate procurement core competencies.

Historically, federal detention in the DOJ was the responsibility of both the USMS and the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). As directed by Congress, the initial objective of the OFDT was to centralize responsibility for detention in order to better manage and plan for needed detention resources without unwanted duplication of effort or competition with other DOJ components. In March 2003, the INS was transferred into DHS. Much of the INS detention responsibilities were included in DHS’s ICE. Although the OFDT has an Interagency Agreement with ICE, the OFDT stated that ICE infrequently uses OFDT’s services (e.g., negotiate and manage contracts for private detention beds). According to the OFDT, it has no leverage to force ICE to use its services.

Federal detainees are generally individuals housed in jails while awaiting trial or sentencing. In contrast, federal prison inmates are generally individuals serving a sentence of imprisonment after conviction for a violation of the federal criminal code. The Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) is responsible for federal prison inmates.

See Appendix III for an example of a cost sheet form and instructions. According to the USMS Intergovernmental Agreement Program Policies and Procedures Manual (IGA Manual), if a detention facility is interested in housing federal detainees, it must complete a Form USM-243 “Cost Sheet for Detention Services” (cost sheet) as part of the application process. A jail-day rate is the amount paid to a detention facility to house one person detained for one day and begins on the date of arrival, but does not include the date of departure.

See Appendix VI for a copy of the current Detention Trustee’s memorandum, dated March 17, 2006.

In a memorandum dated June 6, 2006, the OIG discussed the basis for its disagreement with the OFDT. See Appendix VII for a copy of the memorandum.

Actual costs refer to costs incurred by a detention facility. According to OMB Circular A-87, for actual IGA costs to be allowable costs must be: (1) necessary and reasonable; (2) authorized or not prohibited under state or local laws or regulations; (3) in conformity with laws, regulations, and terms and conditions of the award; (4) accorded consistent treatment; (5) in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles; (6) net of all applicable credits; and (7) adequately documented.

OMB Circular A-87 establishes the principles and standards for determining allowable costs associated with agreements for goods and services obtained by the federal government from state, local, and federally recognized Indian tribal governments.

An IGA is usually indefinite in term until it is terminated by either the detention facility or the USMS.

See Appendix VIII for a copy of the memorandum. The OIG’s response to the memorandum is contained in Appendix IX.

The USMS significantly decreased the number of audits it performed in 2005 due to staffing shortages.

The President’s management agenda includes an initiative to expand Electronic Government (e-gov). The purpose of e-gov is to use internet-based technology to make it easier for citizens and businesses to interact with the government.

As shown in Appendices VII and X, we have expressed concern with the [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] core rate because our individual IGA audits often note significant variances between [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] and the rates supported by the detention facilities’ allowable costs and average daily populations. According to the OFDT, the [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] rate was used because it was based on an entire year of data [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED]. The OFDT acknowledged that the [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] may not accurately reflect each facility’s costs, but said it is the best data it has available. The OFDT also stated that the core rate will be assessed and adjusted, if necessary, as eIGA is populated with expense information.

In this screen shot, the core rate is presented after adjustments, also known as the adjusted core rate.

For purposes of establishing an adjusted core rate, the OFDT said it uses [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED].

In prior memoranda, the OIG identified its specific concerns with the OFDT’s proposed plans for revamping the process for establishing jail-day rates. See Appendices VII and X for a copies of the memoranda.

The Service Contract Act requires contractors and subcontractors performing services on prime contracts in excess of $2,500 to pay service employees in various classes no less than the wage rates and fringe benefits found prevailing in the locality, or the rates (including prospective increases) contained in a predecessor contractor’s collective bargaining agreement. The Department of Labor issues wage determinations on a contract-by-contract basis in response to specific requests from contracting agencies. These determinations are incorporated into the contract.

As a result of OFDT calculating the adjusted core rates incorrectly, the USMS believed it was establishing jail-day rates that [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED] for the facilities in our sample.

To arrive at a cost sheet rate, we reviewed the cost sheets and records of negotiation that were prepared by the USMS IGA analysts. We further adjusted the total allowable costs as appropriate and divided by the average daily population. In some cases, the information presented did not provide us with enough information to evaluate the allowability of costs contained on the cost sheets. Therefore, our calculation could vary from a jail’s actual and allowable costs.

A temporary rate is established when a facility does not have a prior cost history.

In 1976, Congress established FAI under the Office of Federal Procurement Policy. The General Services Administration acts as its executive agent, providing funding and support for FAI. The mission of FAI is to foster and promote the development of a professional acquisition workforce. The FAI details a blueprint for training and development of skills for procurement officials, such as developing, negotiating, and managing business deals, communicating effectively, and analyzing and understanding the marketplace.

“Prisoners” is an Access database that the USMS maintains on detention facilities used to house detainees. The database includes IGA agreements, private contracts for prisoner bed space, and federal detention centers.

Department of Justice, Office of the Inspector General. Audit Report Number GR-60-06-002, The United States Marshals Service Intergovernmental Agreement for Detention Services with the [SENSITIVE INFORMATION REDACTED].