For more than three years, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has been undergoing a broad transformation aimed at focusing the agency on terrorism and intelligence-related matters. In May 2002, in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks (9/11), the FBI established counterterrorism and counterintelligence as its top two investigative priorities. At the same time, the FBI Director formally transferred more than 500 agents from traditional criminal areas to terrorism-related programs.1 These changes were designed to transform the FBI into a more proactive, intelligence-driven agency dedicated to preventing acts of terrorism against the United States and its citizens.

The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) previously reviewed the FBI’s reprioritization efforts, focusing on the internal operational changes that occurred within the FBI between fiscal years (FYs) 2000 and 2003. In that audit we identified the specific types of offenses that the FBI was no longer investigating at pre‑9/11 levels.2 We found that the FBI’s investigative efforts in FY 2003 were generally consistent with its post‑9/11 priorities and that the FBI was performing less work in certain traditional criminal investigative areas and more work in matters related to terrorism.

We performed the current OIG audit as a follow-on to our previous work. In this review, we examined the traditional criminal areas in which the FBI had reduced its investigative efforts and attempted to identify the impact those changes have had on the operations of other law enforcement organizations at the federal, state, and local levels. To accomplish this objective, we analyzed FBI data and documentation from FYs 2000 through 2004 to identify the specific changes in the FBI’s investigative efforts related to traditional crime areas. We also reviewed case management data from the Executive Office for United States Attorneys, which showed changes in the number of criminal matters that the FBI had referred to United States Attorneys’ Offices (USAO) during our review period.

We interviewed headquarters-level officials at the FBI and other federal law enforcement entities, such as the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF); the Department of Homeland Security’s Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE); the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA); the Executive Office of the President’s High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA) program; and the United States Marshals Service (USMS) to determine the impact of the FBI’s changed investigative priorities. Further, to obtain the views of state and local law enforcement officials, we disseminated a web-based survey to approximately 3,500 state and local law enforcement agencies located in the jurisdictional areas of the following 12 FBI field offices: Atlanta, Georgia; Chicago, Illinois; Dallas, Texas; Denver, Colorado; Detroit, Michigan; Los Angeles, California; Miami, Florida; New Orleans, Louisiana; New York City, New York; Phoenix, Arizona; San Francisco, California; and Washington, D.C. We then conducted interviews with field-level federal, state, and local officials within seven of these FBI field office jurisdictions.3 The following sections summarize the results of the OIG’s review.

FBI Criminal Resources

By analyzing the FBI’s field agent allocations (planned resource usage) and field agent utilization (actual use of resources), we first identified the specific changes that had taken place in FBI resource usage between FYs 2000 and 2004. We determined that, through its reprioritization efforts, the FBI had formally reallocated 1,143 field agent positions away from investigating drugs, violent crime, white-collar crime, and other traditional crime and primarily placed these resources in terrorism-related programs. Further, our review of agent utilization data revealed that the FBI had reduced the actual investigative work of field agents related to traditional crimes by more than 1,200 personnel, which is in addition to the formal reallocation of 1,143 field agent positions. According to senior FBI officials, these additional agents were diverted from criminal investigative areas to terrorism-related matters as needs arose.

Allocation of Field Agent Personnel

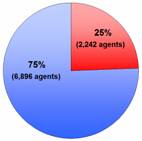

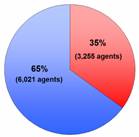

A major element of the FBI’s reprioritization efforts has been to reallocate FBI personnel resources and transfer agents from traditional criminal investigative areas to terrorism-related issues. The following charts provide a FY 2000 to FY 2004 comparison of the allocation of the FBI’s non-supervisory field agent workforce, according to the type of investigative matter to which they were assigned.

| COMPARISON OF FBI FIELD AGENT ALLOCATIONS

IN TERRORISM AND CRIMINAL INVESTIGATIVE MATTERS FISCAL YEARS 2000 AND 20044 |

|

FISCAL YEAR 2000 |

FISCAL YEAR 2004 |

|

|

|

|

| Source: OIG analysis of FBI Resource Management and Allocation (RMA) Office data | |

In FY 2000 the FBI allocated 75 percent of its field agent workforce to criminal investigative areas, predominantly organized crime, drugs, violent crime, and white-collar crime. By FY 2004, the proportion of FBI field agents involved in criminal-related matters declined to 65 percent.

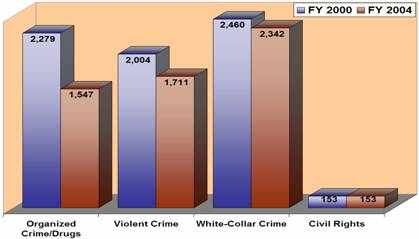

These percentages reflect the FBI’s allocation of fewer field agent positions to criminal areas in FY 2004 compared to FY 2000. The following graph depicts the changes in allocations between FYs 2000 and 2004 within traditional criminal program areas.

| TRADITIONAL CRIME ALLOCATIONS OF FBI FIELD AGENTS

FISCAL YEARS 2000 AND 2004 |

|

| Source: OIG analysis of FBI RMA Office data |

As shown above, the majority of this reduction occurred in the resources allotted for drug investigations. In total, the FBI allocated 1,143 fewer agents to these traditional criminal areas in FY 2004 compared to FY 2000.

Utilization of Field Agent Personnel

In addition to the reallocation of positions, we found that the actual reduction in the number of agents investigating criminal matters was significantly greater than the FBI planned.5 During FY 2004, the FBI allocated a total of 5,753 agent resources to traditional crime matters; however, only 4,474 field agents were actually utilized in these areas, a difference of 1,279 agents.

According to FBI officials, FBI field offices were directed to ensure that no terrorism-related matter went unaddressed, which primarily contributed to the significant gap in the utilization and allocation figures. As a result, the total number of agents actually investigating traditional crime matters was 2,190 less during FY 2004 than during FY 2000. Overall, the FBI had 6,664 agents involved in traditional crime areas in FY 2000, while 4,474 agents investigated such matters in FY 2004.

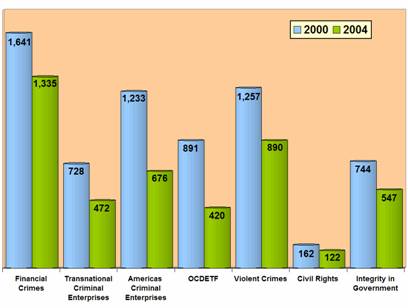

Further analyses revealed that each of the FBI’s current criminal investigative programs experienced agent utilization reductions during this 4-year period, as shown in the following graph. Significant decreases occurred in Americas Criminal Enterprises (45 percent), which is responsible for investigating narcotics trafficking, gang-related crime, and major theft, and Transnational Criminal Enterprises (35 percent), which includes the FBI’s organized crime investigative efforts.

|

FBI FIELD AGENT UTILIZATION IN SPECIFIC CRIMINAL AREAS

FISCAL YEARS 2000 AND 20046 |

|

| Source: OIG analysis of FBI Time Utilization and Recordkeeping data |

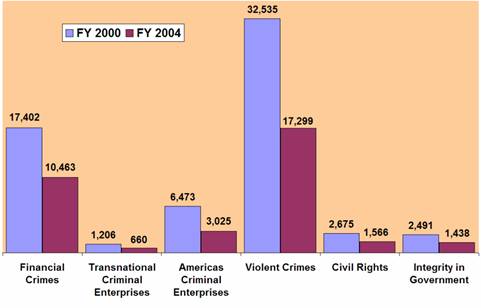

FBI Criminal Casework

For additional insight into the impact of the FBI’s reprioritization efforts, we analyzed data on changes in the number of FBI cases opened. We found that the FBI opened 28,331 fewer criminal cases in FY 2004 than it had in FY 2000, a 45-percent reduction. During FY 2000, the FBI initiated 62,782 criminal investigations, while in FY 2004 the number of investigations declined to 34,451. Within the Criminal Investigative Division, each criminal program experienced a reduction in case openings during our review period, as depicted in the following graph. Notably, the Americas Criminal Enterprises Program initiated over 50 percent fewer cases in FY 2004 than in FY 2000. Additionally, significant decreases in case initiations occurred in Financial Crimes (40 percent) and Violent Crimes (47 percent).

| FBI CASE OPENINGS IN SPECIFIC CRIMINAL AREAS FISCAL YEARS 2000 AND 2004 |

|

| Source: OIG analysis of FBI Automated Case Support data |

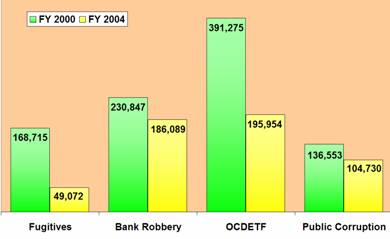

Aside from the decrease in the number of case openings, we also observed a reduction in the number of case serials associated with certain traditional crime matters in FY 2004 as compared to FY 2000.7 The following graph illustrates a general decrease in case serials in four traditional crime areas.

| FBI CASE SERIALS FOR SELECT TRADITIONAL CRIME MATTERS FISCAL YEARS 2000 AND 2004 |

|

| Source: OIG analysis of FBI case serials |

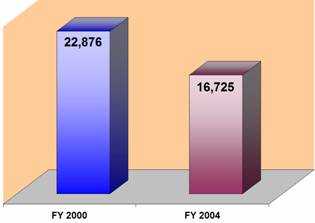

In addition to the results of our FBI casework analysis, we found that the FBI reduced the number of criminal-related matters referred to the USAOs by 6,151, or 27 percent, between FYs 2000 and 2004.8 As the following exhibit shows, the FBI referred 22,876 criminal-related matters to the USAOs during FY 2000; this figure declined to 16,725 criminal matters in FY 2004.

| FBI CRIMINAL MATTERS REFERRED TO THE USAOs FISCAL YEARS 2000 AND 2004 |

|

| Source: OIG analysis of United States Attorney case data |

Impact of Shift in FBI Criminal Investigative Effort

We examined the effect of the FBI’s shift in resources and case openings on the operations of other law enforcement agencies. To assess these impacts, we interviewed FBI and other federal law enforcement officials. We also surveyed and interviewed many state and local officials. The following sections provide an overview of the results of our interviews and survey.

FBI Field Office Perspective

Several FBI field division officials commented that the significant resource reductions in traditional crime areas have considerably affected their investigative efforts. For example, prior to 9/11 one of the FBI’s 56 field offices had at least 9 drug squads. By the time of our fieldwork in April 2005, the number of drug squads in that field office had been reduced to three. Similarly, another FBI field office had at least four drug squads before the FBI’s reprioritization, but is currently operating with two. According to FBI field managers, the reduction in the number of drug squads resulted in a reduction in the number of drug-related investigations.

Reductions in the number of FBI squads were not limited to drug-related matters, but also occurred within the areas of violent crime and white-collar crime. For example, one FBI field office had three individual squads responsible for bank robberies, fugitives, and truck hijacking/cargo theft which, after 9/11, were combined into one squad with a resource level equivalent to only one of the original squads. Additionally, another FBI field office had operated with at least four white-collar crime squads prior to 9/11, but at the time of our fieldwork in March 2005 the office had two such squads.

Some FBI officials we interviewed stated that the FBI’s more limited presence in violent crime and white-collar crime had impaired the law enforcement community’s efforts to address these crime areas, particularly financial institution fraud and bank robberies. They added that state and local law enforcement agencies generally do not have the necessary resources or jurisdictional authority to effectively address many of these violations, and they commented that no other law enforcement agency has been able to compensate entirely for the FBI’s reduced efforts in these areas.

Other Federal Law Enforcement Perspectives

We obtained mixed perspectives from the non-FBI federal agency officials we interviewed regarding the FBI’s reprioritization. At the headquarters-level, while some agency officials stated that they had not observed significant changes in the FBI’s traditional criminal operations, other agency representatives said they noticed a reduction in FBI investigative effort in traditional crime matters.

At the field-level, many non-FBI federal officials we interviewed said they had observed changes in the FBI’s investigative efforts of criminal matters. They commented that the FBI focused much of its attention on terrorism-related matters while pulling back in traditional areas such as drugs and fugitive apprehensions. Despite the FBI’s reduced investigative effort in these traditional crime areas, most non-FBI federal managers in the field said they did not believe their agencies’ operations had been significantly affected, aside from an increase in their caseloads. However, these other non-FBI federal law enforcement officials raised concerns about their resource levels and commented that it will become increasingly difficult for their agencies to assume a greater role investigating traditional crime areas without increased resources.

In addition to the feedback obtained from non-FBI federal investigative officials, representatives from various USAOs said they noted a significant decline in the number of FBI cases brought to them for prosecution. These federal prosecutors also commented that they believed the FBI’s shift in priorities had created investigative gaps in certain crime areas, such as financial crimes.

State and Local Law Enforcement Perspectives

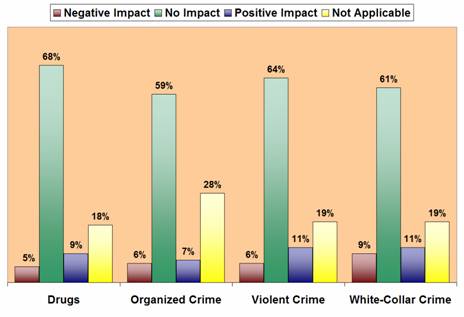

The overall response to our web-based survey of state and local law enforcement agencies located within 12 different FBI field office jurisdictions indicated that state and local law enforcement operations were affected only minimally by the FBI’s reprioritization. Our survey contained several questions inquiring as to whether the responding agency’s investigative efforts had been affected by the FBI’s reprioritization in various criminal areas, such as drug-related crime and white-collar crime. Participants were provided a scaled response to select not only the type of impact but also the magnitude of that impact.9 The following graph illustrates the perceived impact of respondents for traditional crime matters.10

| SURVEY RESULTS OF THE IMPACT ON STATE AND LOCAL LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCIES’ TRADITIONAL CRIME INVESTIGATIONS |

|

| Source: OIG analysis of survey responses |

As shown in this graph, only a small percentage of the state and local respondents indicated that their operations had been impaired by the FBI’s reprioritization. However, in the white-collar crime area, more agencies said they were negatively affected (9 percent of respondents) than in other crime areas (5 to 6 percent of respondents).

In addition to questions related to these general traditional crime areas, our survey included questions related to specific types of violations, such as bank robberies and gang-related activity. Although the answers to these questions mirrored the results of the overall investigative areas – a majority of respondents said their operations were only minimally affected by the FBI’s shift in priorities – we did identify some matters, such as bank robberies and financial institution fraud, in which respondents indicated a greater negative impact caused by the FBI’s reprioritization.

To follow-up on our survey, we interviewed state and local law enforcement officials in 7 of the 12 geographic areas to which the survey was disseminated. In these interviews, the officials described the impact that the FBI’s shift in investigative priorities had on state and local operations. These discussions were more detailed than the survey results indicated, and many officials discussed specific concerns they had with the FBI’s post‑9/11 shift in investigative priorities.

In general, state and local law enforcement officials commented that their caseloads have increased following the FBI’s reprioritization. Officials at several of these agencies expressed concern that they do not have adequate resources to address this increased volume. Moreover, some of these officials stated that the complex and far-reaching crimes that the FBI had been handling often exceeded their departments’ resource levels, expertise, and jurisdictional authority.

During our discussions with state and local law enforcement representatives, we also asked for information on specific crime areas in which they had noticed an impact following the FBI’s reprioritization. According to these officials, the primary area that their agencies were not able to adequately address alone was financial crimes, especially matters related to financial institution fraud. To a lesser extent, several local law enforcement agencies observed reduced involvement by the FBI in the investigation of gangs and bank robberies, which some local officials stated had caused a gap that the local agencies have been unable to completely fill.

Specific Crime Areas Affected by the FBI Reprioritization

Through our discussions with FBI and non-FBI law enforcement officials, we identified and focused on several specific crime areas that these individuals said were negatively affected by the FBI’s reprioritization efforts. In addition, our discussions with the FBI and other federal law enforcement agencies revealed areas such as identity theft and fugitive apprehension in which it appears that the federal government’s response should be addressed in a more coordinated manner.

Financial Crimes

Our data analyses and fieldwork revealed that the FBI had significantly reduced its investigations of financial institution fraud (FIF), especially less significant, low-dollar incidents. Between FYs 2000 and 2004, the FBI reduced the number of agents addressing FIF matters under $100,000 from 111 agents to 20. Based on our interviews and data analysis, we concluded that this decreased effort created an investigative gap that no other law enforcement agency had substantially filled. Several local law enforcement officials stated that many of these crimes were going unaddressed as a result of the FBI’s reduced presence in this area. Similarly, discussions with USAO representatives and analysis of USAO criminal data showed that generally no other law enforcement agency had assumed a greater investigative role on FIF matters to compensate for the FBI’s reduced effort in this area.

To a lesser extent, our data analysis and interviews revealed that a gap existed within the law enforcement community related to telemarketing and wire fraud. Comparing FY 2004 to FY 2000, the FBI used fewer agents to address telemarketing and wire fraud, opened fewer such cases, and referred fewer telemarketing fraud matters to the USAOs. According to FBI and local law enforcement officials, other law enforcement agencies were unable to assume a greater investigative role in these areas because they lacked sufficient resources, technical capability, and jurisdictional authority.

In addition, according to FBI data, the FBI experienced reductions in both its overall agent utilization and case openings between FYs 2000 and 2004 on health care fraud investigations, even though it is the FBI’s second highest national priority for financial crimes. Our analysis of USAO data showed similar results – the FBI referred fewer health care fraud matters to the USAOs in FY 2004 than in FY 2000. Other federal agencies increased the number of such matters referred to the USAOs, but not nearly to the extent of the FBI’s reduction. At our exit conference, the FBI provided evidence that its efforts related to health care fraud had increased in FY 2005 compared to FY 2004.

Corporate fraud is the FBI’s top financial crime priority nationally. In accordance with this ranking, the FBI utilized more agents on corporate fraud investigations and referred more corporate fraud matters to the USAOs in FY 2004 than in FY 2000.

Criminal Enterprises

In this section, we assess the FBI’s investigative efforts with regard to criminal enterprises, which include drug trafficking, gangs, and organized crime. The FBI’s greatest reduction in agent resources between FYs 2000 and 2004 occurred in its drug-related investigations, resulting in fewer drug cases being opened and a decreased overall effort in investigating drug crime. According to the FBI, it has focused its limited resources on dismantling major drug trafficking criminal enterprises rather than on low-level narcotics trafficking investigations. The DEA field managers we interviewed stated that their drug-related efforts had not been negatively affected by the FBI’s reprioritization in the large metropolitan areas, but some of these officials were concerned that an investigative gap existed in smaller urban areas in which prior to 9/11 the FBI was the predominant federal agency addressing drug crime. Many of the state and local law enforcement officials we interviewed noted that their drug-related operations had not been adversely affected by the FBI’s change in priorities.

Our analysis of USAO data revealed that the FBI had submitted almost 1,600 fewer drug-related criminal matters to the USAOs in FY 2004 than it had in FY 2000. Other federal law enforcement agencies, particularly the DEA and ATF, increased the number of drug trafficking matters that they referred to the USAOs between FYs 2000 and 2004. However, these increases did not fully compensate for the overall decrease in drug-related matters referred to the USAOs. The following table details the drug trafficking matters received by the USAOs in FYs 2000 and 2004.

| OVERALL DRUG-RELATED MATTERS RECEIVED BY THE USAOs

FISCAL YEARS 2000 AND 2004 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY 2000 | FY 2004 | Number Change |

Percent Change |

|

| All Agencies | 20,331 | 18,368 | -1,963 | -10% |

| FBI | 3,292 | 1,699 | -1,593 | -48% |

| DEA | 10,053 | 10,296 | 243 | 2% |

| ICE | 5,683 | 4,834 | -849 | -15% |

| ATF | 464 | 779 | 315 | 68% |

| Source: OIG analysis of United States Attorneys’ central case management system data | ||||

Similar to the FBI’s reduced investigative effort in drug-related crime, the FBI experienced a reduction in its organized crime effort between FYs 2000 and 2004. We found that the FBI utilized 35 percent fewer agents on organized crime matters, resulting in fewer organized crime case openings and referrals to the USAOs since FY 2000. Several USAO officials that we interviewed commented that the FBI’s reduced organized crime effort had a negative effect in their jurisdictions.

In contrast to the FBI’s decreased emphasis on drug crimes and organized crime, the FBI has increased its investigation of gangs over the past few years. Data revealed that the FBI essentially maintained the same level of agents investigating gang-related matters in FY 2004 than it had in FY 2000. Moreover, the FBI initiated more cases on gang matters during FY 2004 than during FY 2000.

However, our fieldwork revealed that the law enforcement community in many metropolitan areas believed they lacked useful communication regarding gang-related activity and investigations. Despite the number of agencies addressing these matters, we were told that the FBI, the ATF, local police and sheriff’s departments, and other agencies in several large cities did not adequately coordinate gang-related efforts. For example, we were told of instances in which multiple agencies in a city targeted the same gang without knowing about the other agencies’ efforts. We believe the FBI should seek a more coordinated approach with other members of the law enforcement community to successfully combat gangs.

Fugitive Apprehension

Our analysis and review of FBI data showed that the FBI has reduced its efforts in fugitive-related investigations since FY 2000. In line with our analysis, USMS officials at several of the district offices we visited remarked that they had noticed a lessened effort by the FBI in fugitive-related matters, although they said this change had not affected their ability to address an increased caseload. Moreover, the majority of state and local law enforcement agency representatives we interviewed did not indicate that their work had been negatively affected by any changes in the FBI’s efforts with respect to fugitive-related matters. However, during our discussions with executives at the FBI and the USMS about fugitive operations, we found that the relationship between the agencies was strained and that there was little agreement about the types of cases each agency would work in order to avoid duplication of effort.

Bank Robberies

Another area in which the FBI has reduced its efforts since 9/11 is the investigation of bank robberies. According to the FBI’s data, the number of agents handling bank robberies decreased by approximately 30 percent between FYs 2000 and 2004. Both FBI and non-FBI officials agreed that the FBI was no longer addressing bank robberies as aggressively as it had prior to 9/11.

According to state and local officials, the primary effect of the FBI’s reduced role in bank robberies was an increase in their caseloads. However, a few state and local officials indicated that the FBI’s reprioritization had created a gap in bank robbery investigations for which they were unable to compensate.

Identity Theft

Identity theft was cited as a major concern by the majority of state and local law enforcement agencies we interviewed. Officials at these agencies viewed identity theft as an emerging criminal issue and expected criminal activity in this area to increase in the future. Although we found that several federal agencies, including the FBI, are involved in investigating identity theft to varying degrees, we found no coordinated approach for combating this crime. Local law enforcement officials said they are, at times, confused about which agency to turn to for assistance. Overwhelmingly, local law enforcement agencies conveyed the need for the development of a federal strategy to combat identity theft at all levels of law enforcement.

Public Corruption

Public corruption is the FBI’s highest non-terrorism criminal investigative priority. As a result, field offices considered these matters of utmost importance in their criminal investigative efforts. Despite this, the FBI’s agent utilization data revealed an overall reduction on public corruption matters from FYs 2000 to 2004. Additionally, the FBI opened fewer public corruption cases during FY 2004. It also appeared that some field offices were not giving these matters sufficient emphasis given its priority status. As a result, the FBI has implemented an initiative to review the public corruption efforts within its field offices to ensure that this crime area receives adequate attention. At our exit conference, the FBI provided evidence that its resource utilization in public corruption had significantly increased in FY 2005 compared to FY 2004.

Other Crime Areas

FBI and non-FBI law enforcement officials also raised concerns about their investigative efforts related to child pornography, human trafficking, and alien smuggling. The primary problem for federal agencies, including the FBI, was a lack of resources to adequately address these crimes. In addition, state and local law enforcement officials said their agencies lacked sufficient resources, technical capability, and jurisdictional authority required to investigate these matters. Moreover, in certain locations we identified a lack of coordination between the FBI and ICE on these types of investigations.

Relationships with Others in the Law Enforcement Community

Communication and coordination among law enforcement agencies at the federal, state, and local level is crucial to effective and efficient law enforcement. Given its broad range of investigative jurisdiction, the FBI has significant contact with other law enforcement personnel at each of these levels. With the FBI’s reprioritization and resulting reduced focus on traditional crime areas, the FBI’s relationships with other law enforcement officials, who will more often address these matters instead of the FBI, are critical.

According to the majority of FBI managers and other law enforcement officials we interviewed, the overall relationships between the FBI and other law enforcement agencies has improved over the last few years. These sentiments were voiced by officials at both the headquarters and field office levels. State and local law enforcement officials also indicated that the FBI has shared more terrorism-related information with them since 9/11. However, while they welcome this intelligence information, these officials said they would like the FBI to share more traditional information related to crime areas such as gangs.

In several cities we visited, monthly meetings of law enforcement agency managers within a jurisdiction were highly regarded. According to many officials, these meetings fostered and maintained good working relationships among the law enforcement community. Additionally, these meetings provided an opportunity for agencies to share ideas and information surrounding current investigative efforts. However, FBI managers at some field divisions told us that such meetings were not occurring in their jurisdictions.

OIG Conclusions and Recommendations

Since the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the FBI has attempted to transform itself into a more proactive, intelligence-driven law enforcement agency with a greater emphasis on counterterrorism and intelligence gathering. As part of this process, in May 2002 the FBI issued a new set of priorities and transferred a significant number of agent positions from traditional crime areas to terrorism-related programs. This reprioritization has affected not only the FBI’s operations but also the investigative operations of other law enforcement agencies.

Our analyses of FBI agent utilization data revealed that the FBI has lessened its efforts to combat traditional crime even more than it had planned. Further, the FBI opened fewer criminal cases and referred fewer criminal matters to the USAOs throughout the country in FY 2004 compared to FY 2000.

The effects of the FBI’s shift in priorities and resources on other law enforcement agencies’ operations varied from agency to agency, and often from crime area to crime area. Still, our review identified specific crime areas, such as financial institution fraud and bank robberies, in which other law enforcement officials said the FBI’s reduced investigative activity has hurt their ability to address the crime problem in their area and has left an investigative gap.

In our report, we provided seven recommendations to assist FBI management in the allocation of its agent resources and for improving specific areas of its operations. These recommendations include: (1) assessing investigative need among its various programs to establish realistic and practical personnel projections; (2) pursuing an interagency working group on identity theft; and (3) seeking a more coordinated approach in the areas of fugitive apprehension, child pornography, alien smuggling, and human trafficking.

* The full version of this report includes a limited amount of information that the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), and Executive Office for United States Attorneys (EOUSA) considered to be law enforcement sensitive and therefore could not be publicly released. To create this public version of the report, the OIG redacted (deleted) the portions of the full report that were considered sensitive by the FBI, DEA, and EOUSA; and we indicated where those redactions were made.

- Traditional crime matters include narcotics trafficking, organized crime, violent crime, white-collar crime, and civil rights.

- Department of Justice, Office of the Inspector General. Audit Report Number 04-39, The Internal Effects of the FBI’s Reprioritization, September 2004.

- For our interviews with state and local officials, we spoke with the major police department located in each city we visited. In addition, we judgmentally selected police departments based on responses to the OIG survey, choosing agencies that indicated they had been either negatively or positively affected by the FBI’s reprioritization.

- We categorized FBI activities as terrorism-related or criminal-related based on the program in which the work was captured. We considered terrorism-related work to be captured in the National Foreign Intelligence, Domestic Terrorism, and National Infrastructure Protection/Computer Intrusion programs. We considered criminal-related work to be captured in the Civil Rights, Criminal Enterprise Investigations, Cyber Crime, Organized Crime/Drug, Violent Crime/Major Offenders, and White-Collar Crime programs.

- Resource allocations reflect the FBI’s planned resource usage, while resource utilization indicates the actual time that FBI field agents spent performing their duties.

- During FY 2004, the FBI restructured its Criminal Investigative Division in an effort to better reflect current trends in criminal activity. Included in this restructuring was the creation of new programs, such as the Americas Criminal Enterprises. We adjusted the data to reflect this current program arrangement for both FYs 2000 and 2004.

- FBI agents submit documents reflecting work on a case to the appropriate case file. Each document entry receives a serial, or tracking, number and is known as a “serial.”

- The figures presented for criminal-related matters include all non-terrorism related referrals to the USAOs. For purposes of this report, we considered the matters referred to the USAOs that are categorized as Internal Security Offenses to be terrorism-related.

- Participants were provided a scaled response to select whether the impact was positive or negative, and the magnitude of such impact. A negative impact was defined as an agency being impaired by the FBI’s shift in priorities, such as if the agency experienced severe difficulty in handling the type of investigation listed. A positive impact was defined as an agency benefiting from the FBI’s reprioritization, such as if the agency significantly enhanced its operations to successfully address the investigative area in question.

- We distributed our survey to 3,514 agencies, and 1,265 agencies submitted a response. However, not every agency answered each question and in some instances agencies submitted multiple responses. Detailed information on the survey instrument, recipients, respondents, and responses can be found in Appendices I, VIII, IX, and X of this report.