- We found that the process used by EOUSA and the USAOs to allocate personnel resources has weaknesses. For example, EOUSA does not regularly collect reliable and specific data to make fully informed resource allocation decisions and to use in reporting statistical data to others, including to the Attorney General and Congress. We also found data inconsistencies in the systems used to record time and casework information, which occurred because the time and case reporting guidance for USAO employees were too general and implementation of the guidance varied among USAOs. In addition, EOUSA has not developed a process to objectively determine the appropriate staffing levels of individual USAOs. Moreover, EOUSA generally had difficulty reallocating positions from one USAO to another for a variety of reasons.

USAO Personnel Resource Allocation Process

EOUSA informed us that its first priority in distributing appropriated funding is to support the historic base-level of attorney resources among USAOs. According to EOUSA officials, each USAO has been authorized a base level of funding for attorneys that is generally maintained from one fiscal year to the next. EOUSA does not reexamine this base FTE level for each office on a regular basis. However, these base levels may be increased when additional resources are provided to EOUSA.

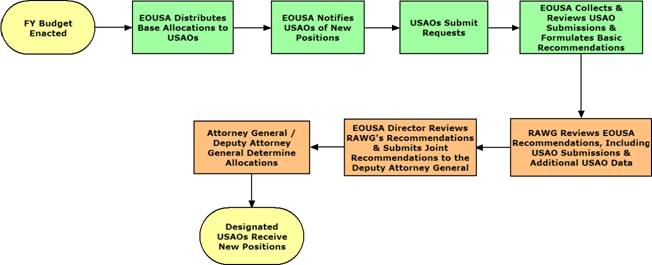

If the annual appropriation provides for additional USAO positions, EOUSA notifies the district offices via a memorandum explaining the type of positions available and the criteria to be considered in determining where to place the resources. Those interested USAOs submit a response to EOUSA explaining the reasons why the district should receive additional positions, including any related data supporting its request. EOUSA, in turn, reviews these responses, formulates basic recommendations, and forwards this information along with other district-specific data to the Resource Allocation Working Group (RAWG).18 This working group reviews the district submissions, as well as EOUSA-provided data and input, revises EOUSA’s recommendations as it deems necessary, and forwards that information to the EOUSA Director, who reviews and makes any necessary revisions to the proposed allocations. The recommendations are then provided to the Deputy Attorney General, who determines where to place any new positions among the USAOs.

The following diagram illustrates the current process for allocating human resources among the USAOs.

EXHIBIT 2-1

HUMAN RESOURCE ALLOCATION PROCESS

Source: OIG-created diagram based upon discussions with EOUSA and USAO officials

Besides direct appropriations, EOUSA also receives additional funding and resources through reimbursable programs, such as the Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force (OCDETF).19 According to an EOUSA official, the process of allocating reimbursable positions may differ from that depicted in Exhibit 2-1 depending on the particular reimbursable program. This official further explained that the Executive Office of OCDETF decides in which USAOs reimbursable positions should be placed, and EOUSA provides the additional resources to those USAOs. Moreover, an appropriation may dictate the specific USAO to which EOUSA should assign new positions. For example, the FY 2005 appropriations language stated that the District of New Hampshire USAO was to receive seven positions in support of Operation Streetsweeper, which was associated with the New Hampshire Violent Crime Task Force. Regardless of the source of funding, EOUSA is responsible for overseeing the allocation of all FTEs among USAOs.

According to an EOUSA official, the majority of new positions allocated among USAOs have historically been provided to address specific initiatives or activities, such as firearms enforcement or counterterrorism investigations, as opposed to being left to the discretion of each U.S. Attorney. For example, in FY 1998 EOUSA allocated 61 attorney positions among the USAOs to address narcotics matters, which was based upon funding directed by Congress for such purposes. However, the congressional reports associated with the FY 2002 appropriations stated that, “all previous congressional guidance to the U.S. Attorneys regarding initiatives and the designation of funds is waived.”20 As a result, this EOUSA official stated that U.S. Attorneys were able to assign these attorney resources as they saw fit and that they have been able to do so for these positions since that time.

USAOs use the United States Attorneys’ Monthly Resource Summary Reporting System (referred to as the USA-5) to record time spent by most USAO personnel on various types of activities.21 According to EOUSA officials, data from the USA-5 is used for statistical reporting purposes, including ad hoc requests from the Attorney General, Congress, and the public. Additionally, EOUSA uses USA‑5 data when considering how to allocate human resources among USAOs, and the data is relied upon, in part, for determining and justifying EOUSA’s annual budget requests.

In the USA-5, USAO personnel assign time to various categories according to the types of matters or cases they have worked on, such as violent crime. Moreover, USAO personnel have the ability to record time to a more specific area by selecting a subcategory – a USA-5A designation, such as criminal gang prosecution – associated with the particular USA-5 category chosen.22 According to the USA-5 manual, the USA-5A categories were established to report to senior Department managers and Congress the number of resources being expended on priority areas. However, the use of USA-5A categories is not mandatory.

USAO personnel using the USA-5 system can record either the actual number of hours worked or the percentage of time spent addressing various prosecutorial matters electronically or on a paper form. The USA‑5 system then translates the information into FTEs.23

USAO personnel are required to enter time into the USA-5 system, at a minimum, on a monthly basis. According to an official from EOUSA’s Case Management Staff, it is each USAO's responsibility to ensure that the data entered into the system is reliable. Each USAO submits a monthly transmission of its USA‑5 data to EOUSA, which is then uploaded by EOUSA into its database. EOUSA maintains this utilization data in a summary format for each district but is unable to compile detailed information on the amount of time individual AUSAs spend on particular types of matters. As a result, EOUSA is only able to identify the total amount of time spent by each position type, such as attorneys or paralegals, on various investigative areas within each USAO.

In FY 2008, EOUSA implemented a new version of the USA-5 system that allows it to review utilization data at the employee level. With this new system, EOUSA is able to review a district’s utilization data without having to wait for it to be submitted by individual USAOs. In addition, EOUSA now has the ability to review the time records of specific individuals. With this information, EOUSA can assess the amount of time, including additional hours beyond an 8-hour day, that is worked by attorneys, while in the past EOUSA could only identify the aggregate time worked by all attorneys in a USAO.

USAOs use the Legal Information Office Network System (LIONS), which became operational in 1998, to manage and record casework information, including matters referred by investigative agencies and cases prosecuted.24 When first implemented, LIONS was a decentralized system that required each USAO to transmit case information to EOUSA manually. In 2003, EOUSA created the National LIONS (N-LIONS), which eliminated the manual transmission process. The N‑LIONS is a centralized system that is automatically updated with case information from each district’s LIONS. EOUSA utilizes the N-LIONS to assist in formulating annual statistical reports and obtain information to respond to various inquiries from Congress, the Attorney General, and the public.

USAO personnel must complete several fields when entering information into LIONS, such as the type of matter or case, the agency referring the matter to the USAO, and the final disposition of the case. In particular, LIONS contains two fields that define the type of case – the program category for criminal matters and the cause of action for civil matters. Each field has its own set of codes that identifies the specific area being addressed for that particular matter or case, such as domestic terrorism, bank robbery, or civil rights. However, these codes are different from the categories used by USAO personnel when recording their time using the USA-5 system.

Although the LIONS User’s Manual describes the codes that should be used to categorize cases, EOUSA has no mechanism to determine if a record has been classified and reported correctly. Instead, EOUSA relies upon case certifications from each district office in which USAO personnel are required to verify data in their local databases on a semi-annual basis25 Following this certification by individual USAO personnel, the U.S. Attorney must certify the accuracy of his or her district’s data as a whole before it is submitted to EOUSA.

Concerns with Resource Allocation

Our audit identified weaknesses in the way EOUSA evaluates the needs of individual USAOs. In addition, while EOUSA considers both attorney utilization and casework data in determining where to allocate new positions, we found substantial deficiencies in the USA-5 and LIONS data that call into question whether the attorney utilization and casework data should be relied upon. As a result, some offices may be given additional resources based, in part, on inaccurate data when, in fact, other USAOs are in greater need of those positions. Moreover, EOUSA officials stated that it is very difficult to reallocate positions among USAOs and that any such attempt is regularly met with opposition by those USAOs slated to lose positions.

Lack of Comprehensive Resource Needs Assessment

In April 2006, the AGAC began an unsuccessful attempt to create a formula to compute appropriate staffing levels but concluded that it was not feasible to develop a simple, reliable, and objective formula to determine how personnel should be allocated among the USAOs26 This conclusion mirrored those of previous EOUSA efforts. As a result, EOUSA has been unable to objectively determine the resource needs of the USAOs and thus cannot statistically justify the reallocation of current FTEs. The EOUSA Director stated, however, that even if such a model were available, one of the AGAC’s working groups concluded that it would be politically impractical to reallocate existing positions among USAOs.

Weaknesses in the Reporting of Utilization Data

Given the nature of the data, the USA-5 system relies upon the self-reporting of each employee and therefore is only as valid as the information reported by USAO personnel. During our review of the time reporting system, we identified weaknesses in the methods used to identify and categorize the various types of activities worked by USAO personnel, the level of detail to which time is recorded, the frequency of recording time, the format used to record time, and the cultural environment regarding the time reporting process. Each of these weaknesses can increase the inaccuracy and incompleteness of the USAOs’ human resource utilization data. We discuss each of these issues in turn.

Categorization of Time – EOUSA does not have a standardized categorization method that USAO personnel use when recording time to specific activities. This creates a dilemma for AUSAs, particularly with respect to cases involving multiple offenses. For instance, an AUSA may be addressing a case associated with terrorism, narcotics, and fraud. However, there is no standard approach for recording the AUSA’s activities on such a multi-faceted case. As a result, AUSAs may not record their work on these types of cases consistently and the USA-5 may not accurately reflect the amount of time AUSAs spend on certain activities. In order to ensure that the data is as accurate as possible, we believe that EOUSA should evaluate the current USA‑5, determine how AUSAs should record time for cases that involve multiple offenses, and issue clear guidance.

Recording Time to More Specific Activities – As noted above, attorneys record time to broad USA-5 categories, such as violent crime, and also have the ability to record time to a more specific activity by selecting a USA-5A category, such as criminal gang prosecution, that is associated with the particular USA-5 category chosen. However, use of the more specific USA‑5A categories is not mandatory. Based upon our review of the resource utilization data, we determined that attorneys generally do not record time to these more specific categories. EOUSA officials stated that not every case may necessitate a USA‑5A category. For example, if a matter involves a simple drug trafficking matter, there may not be a corresponding USA-5A category.

Nevertheless, we believe that USAOs are significantly underutilizing these more specific USA-5A categories when it would have been applicable to record time to these activities. We determined that only 13 to 16 percent of the total reported attorney FTEs were associated with a USA‑5A category during any fiscal year in our review period. As a result, EOUSA is unable to provide a detailed description of how much time was expended by USAOs on specific types of activities, such as gang prosecutions, health care fraud, and terrorism-related matters, to those requesting this information, including senior Department managers and Congress. We believe that the use of USA-5A categories should be mandatory, if a USA-5A category is applicable, when recording time in the USA-5 system.

During our discussions with the EOUSA Director, he agreed that attorneys do not always record their time to the specific activities on which they work and that this was of great concern to him. The Director stated that it is imperative that USAOs accurately reflect this information because the USA-5 data is a significant factor considered when determining where to place new attorney positions. He said that U.S. Attorneys have often informed him that their office’s USA-5 data is inaccurate and should not be relied upon in making allocation decisions. The Director said he will no longer accept U.S. Attorneys’ explanations for discrepancies in the recordation of USA-5 data and will consider USA-5 data at face value as an accurate depiction of USAO personnel utilization.

Frequency of Recording Time – Another factor affecting the accuracy of USA-5 data involves the varying methods used by USAOs for capturing AUSA time. As mentioned above, USAO personnel must record time to the USA-5 system at least monthly. As confirmed during our discussions with USAO personnel, AUSAs may decide to enter their time into the system daily or with any other frequency that satisfies the monthly reporting requirement. We believe the probability of incorrect data is much greater when there is a significant span of time between the actual work performed and the time those activities are recorded in the USA-5 system. While EOUSA officials said they encourage USAO personnel to enter time on a daily basis, no policy has been established to require more frequent data entry than the current monthly requirement. We believe that implementing a policy requiring at least weekly entry would help improve the accuracy of USAO human resource utilization data.

Format Used to Report Time – As previously mentioned, USAO personnel can either record their time on a paper form or electronically. The USA‑5 paper form contains 4 pages and lists 51 USA-5 categories to which AUSAs can record their time27 Although an electronic version of this form is available to USAOs, USAO personnel we interviewed stated that the electronic form is not user-friendly. Therefore, some USAO personnel decided to complete the paper format of the USA-5, which subsequently must be entered electronically into the USA-5. We believe that use of the paper form to enter attorney time is more cumbersome and time-consuming than the electronic form because it requires additional work by USAO personnel. Therefore, we believe that EOUSA needs to develop a more user-friendly electronic form for USAO personnel to record their time.

Timekeeping – During our discussions with EOUSA and USAO officials, some USAO personnel stated that completing the USA-5 in an accurate manner requires too much time. They noted with approval that while private law firms require personnel to record time in small increments throughout each day, this type of timekeeping is not required of USAO personnel. Some officials remarked that USAO personnel view their primary objective as working cases rather than accurately depicting the time expended on specific activities. However, with appropriate guidance and a streamlined approach, we do not believe that recording time at least weekly in the USA‑5 system is too onerous or similar to the private sector requirement and would not require a significant level of additional effort.

Weaknesses in Casework Data

During our review of EOUSA’s casework reporting system, we identified weaknesses in the methods used to identify and categorize the various types of cases handled, the timing of casework data entry, and oversight of the casework system.

Categorization of Cases – According to EOUSA officials, the process for entering information into LIONS varies by district. Some districts have a centralized process in which a few people enter all case-related information into LIONS, while others have a decentralized process in which many people enter case information into LIONS. As a result, the categorization of case information in LIONS relies on the discretion of the USAO personnel entering it and may result in districts classifying similar cases differently. For example, two districts may each have a case involving firearms and drug trafficking violations. One district may identify its case using the drug trafficking program category code, while the other district identifies its case using the firearms code. Therefore, as noted by EOUSA officials, the information contained in LIONS will be inconsistent and result in reporting imprecise information on the number of specific types of cases being handled by USAOs.

Timing of Data Entry – During our initial review of data accuracy and completeness, we performed testing on the various date fields contained in LIONS, including the filing date, system filing date, and fiscal year fields. We identified delays in USAOs entering case filing information, as well as inconsistencies with the date information contained in LIONS.

Among the several date fields contained in LIONS, we focused our review on the filing date and system filing date fields. The filing date field indicates the actual date a matter is filed in court, while the system filing date field reflects the date when the filing date is entered into LIONS. For statistical reporting purposes, EOUSA relies upon the date when the case information is entered into LIONS, or the system filing date. However, there can be a lag between these two dates and the extent of the lag can affect statistical reporting and management assessments of USAO workload. For example, a matter may be filed in court in July 2007, yet the data may not be entered in LIONS until November 2007, which would reflect a system filing date of November 2007. Consequently, EOUSA would include this matter as a new case filing in FY 2008 when, in fact, the matter was actually filed in court in FY 2007. As a result, a district’s workload may appear to be greater or less than it actually is during a given fiscal year, which can affect allocation and budget decisions.

As part of our casework analyses, we found a significant number of cases in which there was a lag between the date the matter was filed in court and the date the information was recorded in LIONS. Specifically, we identified 254,481 cases, or almost 40 percent of the total 680,551 criminal and civil cases filed by USAOs between FYs 2003 and 2007, where there was a difference between the date the matter was filed and the date of entry into LIONS. The following table shows the span of time between the case filings and entry into LIONS for these 254,481 cases, as well as the percentage of the total for each range of time.

| EXHIBIT 2-2 SPAN OF TIME BETWEEN CASE FILINGS AND ENTRY INTO LIONS |

||

|---|---|---|

| Range | Number of Cases | Percentage of Total28 |

| 1 to 30 Days | 179,991 | 70.73% |

| 31 to 180 Days | 53,521 | 21.03% |

| 181 Days to 365 Days | 14,596 | 5.74% |

| 1+ to 2 Years | 4,220 | 1.66% |

| 2+ to 5 Years | 1,829 | 0.72% |

| 5+ to 10 Years | 224 | 0.09% |

| Greater than 10 Years | 100 | 0.04% |

| Total | 254,481 | 100.01% |

| Source: OIG analysis of LIONS data | ||

EOUSA and USAO officials said that the case filing date should be entered in LIONS shortly after the matter is filed, a period they defined as no longer than 30 days after the matter is filed in court. We understand that the filing date cannot always be entered into LIONS immediately following the matter being filed in court and thus believe that a 30-day window is reasonable. As shown in the preceding table, the information was entered into LIONS for the majority of cases within the first 30 days of the matter being filed. However, we identified 74,490 cases (or 29 percent) with system filing dates greater than 30 days following the actual case filing dates. We are concerned with the significant number of cases that were entered into LIONS in excess of 30 days after the official court filing date and the effect that this lag can have on statistical reporting and management assessments of USAO workload.

When we presented this information to EOUSA officials, they offered various explanations for the delays, including resource constraints leading to case entry backlog, as well as the possibility of delays in receiving the necessary court documents. We also inquired about the more significant intervals that we identified in the data. For example, we found one matter that was shown as being filed during FY 1994, yet the system filing date indicated that this case filing was not entered until FY 2005. In response, EOUSA officials explained that this can occur when cases are “reopened” by USAO personnel, which happens when case information is updated in LIONS after the case had been closed. As a result, the system filing date reflects the date the updated information was entered in LIONS. This process, however, results in a statistical misrepresentation of cases filed by USAOs. Specifically, these “reopened” cases are shown as new cases when they were previously counted as new cases in prior fiscal years. Consequently, the actual number of cases filed per district office and by specific activity is imprecise, which could cause inaccurate assessments by management. EOUSA officials said that they cannot identify the number of instances in which this occurred unless they reviewed each individual case file.

Oversight of LIONS – EOUSA relies on the USAOs to review the information in LIONS to ensure its accuracy. In addition to EOUSA’s guidance, LIONS contains error edits and drop-down lists that serve as a quality control device for entering casework data29 However, during our review of the LIONS data we discovered inconsistencies in the completeness and accuracy of the data that call into question whether the automated controls over the system are operating as intended. In particular, we identified several instances in which records contained mandatory fields that were unpopulated. For example, LIONS system documentation indicates that the field that is designed to identify the referring agency for incoming cases is mandatory. However, this field was not always populated in the data file we received. Although these inconsistencies generally accounted for less than 1 percent of the total number of records in the data file, EOUSA officials were uncertain how or why the system allowed this to happen.

Our review also identified another potential weakness in LIONS concerning immediate declinations. Immediate declinations refer to matters where USAOs expend less than 1 hour reviewing a matter before deciding not to prosecute. We found that no data from the District of Minnesota was included in the immediate declination data file provided to us. When we asked EOUSA officials about this anomaly, they were surprised that information covering several fiscal years would not be listed for an entire district. However, after following up with the district, EOUSA officials confirmed that the Minnesota USAO does not track immediate declinations.

As discussed previously, EOUSA has informed the USAOs that it will no longer accept assertions from USAOs that LIONS data (which originates at the district level) should not be relied upon in making decisions on requests for additional resources. Further, EOUSA officials said that their consideration of such resource requests will be based, in part, upon available data. According to the EOUSA Director, this should be a strong encouragement to the USAOs to ensure that the data originating from their offices is accurate.

Lack of Existing Resource Reallocation

According to EOUSA officials, USAOs have historically maintained a base level of attorney FTEs from one fiscal year to the next and positions are rarely moved from one office to another. Consequently, when different offices’ workloads evolve over time, some offices may be overstaffed while others may be understaffed.

EOUSA officials offered several reasons to explain EOUSA’s difficulty in reallocating positions among USAOs once those positions have been assigned. According to EOUSA, the primary challenge is the resistance and opposition from several sources, including U.S. Attorneys, individual offices, and the AGAC.

According to EOUSA officials, involvement of the Attorney General or Deputy Attorney General is necessary for any widespread reallocation of resources. Moreover, in some instances annual congressional appropriations language specifies that a certain number of positions are to be placed in a specific district office to address a particular prosecutorial initiative. When that initiative is ended, the district office may no longer need those resources for that specific purpose. However, according to EOUSA officials, there is little EOUSA can do to take these positions away from the USAO and reallocate them elsewhere.

The working group that performed the most recent evaluation of the USAO resource allocation process concluded that it was politically impractical to reallocate existing positions among USAOs. The EOUSA Director discussed this conclusion with us and indicated that, although difficult, he believed that reallocation was possible and that EOUSA missed an opportunity to reallocate positions when the USAOs had a significant number of vacancies.

EOUSA was given a congressionally directed opportunity to redistribute resources among districts during the FY 2002 appropriations. In the reports accompanying the Department’s 2002 appropriations, the Committees on Appropriations stated that they had attempted to revise the process of allocating resources among the USAOs to better align USAO staffing levels with their caseloads.30 Some of the actions suggested by the Committees were the use of term positions and transferring specific numbers of personnel to and from certain offices. However, the congressional reports state that each of the suggested actions was rejected by the U.S. Attorneys. As a result, the Committees concluded that EOUSA should step in and distribute human resources and funding among the USAOs so that “the interests of the American people were best served.” To provide EOUSA more freedom in this initiative, the Committees included language in its report to waive previous congressional guidance regarding the designation of funds for specific activities and locations. By March 2002, EOUSA was to submit to the Committee a report on the actions it planned to take.

According to an EOUSA official, EOUSA provided the Committees with a verbal report but did not reallocate any positions. EOUSA officials further told us that they were unaware of any additional congressional language on this topic since that time.

EOUSA has attempted to mitigate some of the resource discrepancies by assigning term positions to USAOs. Term positions are allocated to district offices for a specified time period. At the conclusion of this period, EOUSA has the ability to reallocate those positions to other offices based upon a reassessment of district office needs. Additionally, EOUSA officials explained that they have relied upon the current process for allocating new positions among the USAOs, which requires an evaluation of individual district needs and DOJ priorities, to resolve any staffing discrepancies. However, these officials also stated that there have not been a sufficient number of new positions provided in recent years to significantly alter the historic resource allocation levels of USAOs.

We concluded that EOUSA does not have the necessary information to effectively evaluate and determine the optimal staffing levels of individual USAOs. Although the AGAC attempted in April 2006 to develop an objective model to statistically identify the appropriate level of resources for each district, it concluded that such a model was not feasible.

In addition, the data systems used by EOUSA and the USAOs to help manage personnel resources have significant deficiencies. The USA-5 system was created to capture the time spent by USAO personnel on various activities, while LIONS tracks each district’s casework data. EOUSA considers this information in resource planning and allocation decisions and relies upon this data to answer requests from Congress, the Attorney General, and the public. Given the widespread use of this data, it is important that it be accurate and complete. However, we found problems surrounding the accuracy of the data in both systems and recommend that EOUSA and the USAOs place greater emphasis on accurately and specifically reporting attorneys’ time and casework information.

EOUSA generally has not reallocated existing attorney positions from one USAO to another for a variety of reasons, including opposition from several sources, including individual USAOs that would be affected by the reallocations. Furthermore, EOUSA did not take advantage of a congressionally provided opportunity in FY 2002 to reallocate resources among USAOs.

We believe that EOUSA should take steps to address the data inconsistencies, develop a process to objectively determine the appropriate staffing levels of individual USAOs, and move to ensure that allocations are in accord with that process.

We recommend that EOUSA:

- Establish a standardized process for tracking time to cases involving multiple offenses to more accurately reflect attorney utilization.

- Implement a policy requiring USAO personnel to record time in the USA-5 system on at least a weekly basis, as well as to record all time to a USA‑5A category when such a category is available.

- Develop a more user friendly electronic form for USAO personnel to report their time in the USA-5 system.

- Implement a standardized approach among USAOs for categorizing cases within LIONS and the USAOs’ new case management system – Litigation Case Management System.

- Ensure that “reopened” cases are not reflected in the statistical reports in the fiscal years in which the cases were reopened.

- More closely monitor the casework data transmitted by USAOs to ensure it is accurate and complete.

- Re-emphasize to the USAOs the importance of utilization and casework data, how the data is used, and the necessity of accurately capturing this data.

- Examine the current staffing levels of USAOs, and develop methods to reallocate resources among USAOs.

Footnotes

- The RAWG, which is one of the AGAC’s working groups, is composed of eight U.S. Attorneys.

- The OCDETF Program is a multi-agency effort created to identify, disrupt, and dismantle the most serious drug trafficking and money laundering organizations.

- U.S. Senate, Departments of Commerce, Justice, and State, The Judiciary, and Related Agencies Appropriation Bill, 2002, S. Rept. 107-42; and U.S. House of Representatives, Making Appropriations for the Departments of Commerce, Justice, and State, The Judiciary, and Related Agencies for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 2002, and for Other Purposes, 2002, H. Rept. 107-278.

- The USA-5 system tracks the time of attorneys, paralegals, and support personnel, as well as the time of Special Assistant U.S. Attorneys (SAUSAs). However, the USA-5 system does not track the time of contractors and students working in USAOs. In addition, the system does not include any case-specific information.

- Each USA-5 category has USA-5A categories associated with it. Additionally, in some instances, the same USA-5A categories apply to multiple USA-5 categories.

- One FTE equates to 2,080 hours.

- According to EOUSA officials, LIONS will be replaced by a new DOJ-wide case management system called the Litigation Case Management System (LCMS). The EOUSA officials stated that the LCMS should be piloted during FY 2009. According to the EOUSA Director, EOUSA is also considering using the LCMS to track attorney time in addition to case information.

- This procedure applies to docket personnel, system managers, line attorneys and their administrative assistants, and supervisory attorneys.

- This initiative began in April 2006 and concluded in June 2008 with the issuance of the U.S. Attorneys’ Procedure entitled Personnel Resource Allocation Process.

- The USA-5 has separate forms to record time to criminal and civil matters. The criminal form is 3 pages and contains 22 USA-5 categories. The civil form is 1 page and contains 29 USA-5 categories. Appendix IV contains a copy of these paper forms.

- Due to rounding, the percentages in this table total 100.01 percent.

- Error edits and lists are designed to prohibit users from entering invalid codes and dates or skipping a required field.

- U.S. Senate, Departments of Commerce, Justice, and State, The Judiciary, and Related Agencies Appropriation Bill, 2002, S. Rept. 107-42; and U.S. House of Representatives, Making Appropriations for the Departments of Commerce, Justice, and State, The Judiciary, and Related Agencies for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 2002, and for Other Purposes, 2002, H. Rept. 107-278.