The purpose of this evaluation was to assess the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives’ (ATF) implementation of the Safe Explosives Act (SEA).11 The SEA was enacted in November 2002 to enhance public safety by expanding the ATF’s licensing authority to include the intrastate manufacture, purchase, and use of explosives; by expanding the categories of “prohibited persons” to be denied access to explosives; by requiring background checks on all individuals who have access to explosives; and by mandating triennial inspections of licensees’ manufacturing and storage facilities.

Explosives are an integral component of the nation’s economy. More than 5.5 billion pounds of explosives are used each year in the United States in a variety of industries and for a variety of purposes, such as aerospace (for ejector seats and separation devices for rocket stages); coal mining; avalanche control; construction; demolition; excavation for foundations and underwater channels; fire suppression systems; law enforcement (exploding dye capsules); metalworking; pyrotechnics; medicine (heart medication and treating kidney and gall stones), manufacturing (inflating automobile airbags and creating synthetic diamonds); and numerous other applications.

Coal mining uses 68 percent of the total amount of explosives sold in the United States. Quarrying and non-metal mining is the second-largest explosives consuming industry, accounting for 13 percent of total explosives sales; metal mining, 8 percent; construction, 8 percent; and miscellaneous uses, 3 percent. West Virginia, Kentucky, Wyoming, Indiana, Virginia, and Pennsylvania, in descending order, are the largest explosives-consuming states, accounting for a combined total of 58 percent of domestic sales.12

Explosives are also used illegally. According to data provided by the ATF’s Arson and Explosives National Repository, over the past 3 years, the ATF received about 700 reports of domestic bombing incidents. (See Appendix I for more information on domestic and foreign bombing incidents.)

The ATF is the chief enforcer of explosives laws and regulations and is responsible for licensing and regulating explosives manufacturers, importers, dealers, and users. The ATF also is responsible for overseeing most regulations involving explosives storage.13 The ATF’s National Licensing Center in Atlanta, Georgia, oversees the receipt, processing, granting, or denial of explosives licenses and permits. The Licensing Center issues 23 different types of licenses and permits governing the manufacture, importing, sales, and use of explosives. Licenses and permits are specific to the class of explosives – high explosives, low explosives, blasting agents, fireworks, and black powder. The ATF’s Enforcement Programs and Services Division oversees the regulatory activities carried out by ATF Inspectors located throughout the ATF’s 23 Field Divisions. The ATF’s Criminal Enforcement Division, comprised of Special Agents, is responsible for investigating illegal commerce and use of explosives.

In addition to the ATF, several other federal agencies have roles in overseeing the manufacture, transport, sale, or use of explosives. For example, the Department of Labor’s (DOL) Occupational Safety and Health Administration is responsible for ensuring the safety of workers who manufacture explosive materials. The Mine Safety and Health Administration, also part of the DOL, is responsible for standards that protect workers who use explosives in mines and quarries, and operates under a Memorandum of Understanding with the ATF related to regulatory inspection activities. The Department of the Interior’s Office of Surface Mining is responsible for limiting damage from blast effects, such as ground vibration and flying rocks near coal mines. Within the Department of Transportation (DOT), the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration is responsible for enforcing laws and regulations related to transporting explosives over highways. The DOT Research and Special Programs Administration is responsible for enforcing packaging and labeling standards. The Coast Guard, which is part of the Department of Homeland Security, is responsible for enforcing laws and regulations related to transporting explosives on the nation’s waterways.

The ATF’s pre-SEA inspection activities. Prior to the enactment of the SEA in 2002, the ATF’s explosives regulation was governed by Title XI of the Organized Crime Control Act of 1970.14 In fiscal year (FY) 2001, the ATF conducted 4,179 explosives-related inspections. Of those, 3,324 were compliance inspections, 839 were new application inspections, and 16 were conducted in response to referrals from the ATF’s Criminal Enforcement Division. Compliance inspections conducted on licensees and permit holders included, but were not limited to, inspection of storage magazines, records of inventory and sales, and compliance with ATF administrative rules. The ATF conducted application inspections before issuing new or renewal licenses or permits. In FY 2001, there were 9,084 federal explosives licensees and permit holders. Based on the data provided, the ATF conducted compliance inspections on 37 percent of licensees and permit holders during that year.

In response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the ATF ordered most of its approximately 500 Inspectors to conduct on-site inspections of all explosives licensees and permit holders in and around major metropolitan areas. In the approximately 120 days following the attacks, this unprecedented special inspection effort resulted in over 5,700 inspections. The ATF characterized these inspections as having a two-fold purpose. The first was to discover and correct any obvious or egregious violations of law or regulations that would facilitate terrorist access to explosives. The second was to encourage licensees and permit holders to increase their vigilance and to report any suspicious activity, purchases, or requests for information, especially from individuals with whom they had not previously done business. In addition to the 5,700 special post-September 11 inspections, the ATF conducted 4,487 explosives-related inspections in FY 2002. Of those, 3,450 were compliance inspections and 1,037 were new application inspections.

The requirements of the Safe Explosives Act. The Homeland Security Act of 2002, of which the SEA is a sub-part, transferred all of the ATF except its alcohol and tobacco tax enforcement and revenue collection functions from the Department of the Treasury to the Department of Justice (the Department). The SEA contains five major provisions regarding the regulation of explosives, which are described below. The first two provisions became effective on January 24, 2003, 60 days after the law was enacted on November 25, 2002. The last three provisions became effective on May 24, 2003, 180 days after enactment.

Provision one added three new categories of persons prohibited from receiving or possessing explosives — aliens (with limited exceptions), persons who have been dishonorably discharged from the military, and individuals who have renounced their United States citizenship. These categories were added to the pre-existing list of categories of prohibited persons that included convicted felons or individuals under felony indictment, fugitives, users of and persons addicted to controlled substances, and persons who have been adjudicated mental defectives or committed to mental institutions.15

Provision two requires that manufacturers and importers of explosives provide samples of their products as well as information on the chemical composition and other information to the ATF’s National Laboratory upon request.

Provision three requires that all persons who receive explosives must hold a federal explosives license or permit. The SEA also created a “limited permit,” which authorizes the holder to purchase and use explosives only within his or her state of residence on no more than six separate occasions during the 1-year term of the permit. Prior to the SEA, persons who transported, shipped, or received explosives in intrastate commerce were not required to obtain a federal license or permit. The “user permit,” which existed prior to the SEA, authorizes the holder to receive unlimited amounts of explosives in interstate commerce during the 3-year term of the permit.

Provision four requires that Responsible Persons of companies that manufacture, sell, or use explosives (e.g., corporate officers, site managers) submit detailed personal information, including fingerprints and photographs, to the ATF. In addition, employees whose jobs afford them access to explosives are required to submit Employee Possessor Questionnaires (EPQs). (See Appendix II.) The EPQs are used by the ATF to conduct background checks to verify that the employees are not prohibited persons.

Provision five requires that the ATF perform on-site inspections of all licensees and permit holders at least once every three years, with certain exceptions, to determine compliance with federal explosives storage regulations. For licensees and permit holders, the ATF must verify, by on-site inspection, that new applicants’ and renewal applicants’ explosives storage facilities meet federal safety and security regulations.16

The ATF’s official workload estimates for implementing the Safe Explosives Act. According to ATF officials, the ATF made limited attempts to determine the number of individuals who would need to apply to the ATF for an explosives license or permit. In 2002, the ATF Acting Director testified before a Congressional subcommittee that the SEA would cause the population of licensees and permit holders to “double, triple, or even quadruple” from the pre-SEA total of approximately 9,000.17

In developing its estimates of the potential population of licensees and permit holders, the ATF relied heavily on information provided by one explosives industry group. The group supplied the ATF with information on intrastate explosives sales to unlicensed individuals.18 The ATF used the information to estimate the number of individuals who might be required to obtain a federal license or permit. ATF Headquarters officials also attempted to determine the potential population by surveying ATF Area Supervisors about state explosives laws in their areas. However, according to ATF Headquarters officials, the information gathered from the Area Supervisors was not helpful and was not used in developing the ATF’s projections.

Using this information, the ATF prepared official estimates for the Congressional Budget Office as well as for the Acting ATF Director’s testimony before Congress.19 The ATF also used the estimates to plan for the establishment of a National Explosives Licensing Center staffed by approximately 40 people to process the expected large increase in applications. Based on cost factors associated with the expected increase in staff, the ATF decided to place the center in Martinsburg, West Virginia, at an estimated cost of $4 million, rather than expand its existing licensing operations in Atlanta, Georgia. In addition, based on the projections, the ATF planned to conduct SEA training for all of its Inspectors and up to 250 of its Special Agents.

However, the population of licensees and permit holders did not increase as much as projected by the ATF. Since the SEA was enacted in November 2002 through September 2004 the population of licensees and permit holders has risen to 12,152, an increase of only about 3,500, not the 18,000 to 36,000 increase projected by the ATF.20 According to the Acting ATF Director at the time and the ATF Assistant Deputy Director for Enforcement Programs and Services, the population did not increase as expected because ATF Headquarters officials did not anticipate that most unlicensed explosives users would hire contract blasters rather than apply for their own federal permit or license. Typically, contract blasters provide services such as destruction of beaver dams and the removal of tree stumps or large rocks. Figure 1 depicts the trend in the population of federal explosives licensees and federal explosives permit holders, along with license and permit application trends.

| Figure 1: New and Renewal Explosives License and

Permit Applications Received, 2001-2004 [Not Available Electronically] |

| Source: Data provided by the ATF’s National Licensing Center. |

ATF efforts to inform industry of the SEA and to issue regulations. To notify industry members about the SEA, the ATF sent letters to licensees, posted frequent updates to the ATF website, and communicated with industry groups. For example, four days after the SEA was enacted, the ATF issued open letters to industry members regarding the provisions of the SEA. In the course of the next month, the ATF distributed fact sheets, press releases, and a poster informing unlicensed explosives users about new licensing requirements. (See Exhibit 1.)

| Exhibit 1: ATF Informational Poster

|

The ATF also centralized its implementation of the SEA by appointing one person as the ATF’s point of contact and a small team for implementing the SEA. Under the leadership of the point of contact, the ATF worked to keep ATF employees and explosives industry members informed about the SEA, coordinated meetings and communication between the ATF and outside groups, and coordinated the training of Inspectors to implement SEA provisions.

The ATF issued formal regulations shortly before the Employee Possessor provisions of the SEA took effect on May 24, 2003.21 The ATF did not issue a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, but instead issued an Interim Final Rule two months prior to the effective date of the second set of SEA provisions.22 If it had issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, explosives industry members would have been afforded the opportunity to comment on the ATF’s plans prior to their implementation. Instead, the interim rule was issued in March 2003, two months prior to the effective data of the SEA provisions related to conducting background checks on Employee Possessors. Industry groups began submitting comments on the Interim Final Rule in June 2003. During our review the ATF told us that it planned to issue its final regulations for implementing the SEA by mid-2005. In its response to a draft of this report, the ATF extended that target to “in or about” October 2006.

On the whole, every industry group we spoke with said the SEA was an important step toward increasing security. Group members said that they did not object to the new categories of prohibited persons created by the SEA and had few specific problems with the interim rule developed and published by the ATF. The group members stated that the ATF’s licensing process did not disrupt their operations and that explosives licensees were generally informed about the SEA’s requirements. One exception, which was resolved quickly, involved Pennsylvania anthracite miners (see text box, next page).

Industry members, however, did express concern about how the ATF initially interpreted the SEA’s impact on explosives transportation. The ATF attempted to increase its oversight of explosives transportation in the beginning of 2003. Citing the SEA’s provision prohibiting aliens from handling explosives, the ATF took the position that Canadian truck drivers and railroad operators should not be allowed to transport explosives into the United States after the DOT issued a regulation exempting these individuals from the SEA’s provisions.23 The DOT, however, cited a statute granting the department and its agencies the authority to oversee all safety-related aspects of explosives transportation.24

Pennsylvania Anthracite Miners Despite the ATF’s efforts to inform explosives industry members of SEA regulations, a group of about 20 anthracite coal miners in rural Pennsylvania failed to timely apply for relevant ATF licenses. After being contacted by the miners’ Congressman, the Special Agent in Charge and the Director of Industry Operations of the ATF’s Philadelphia Field Division sent Special Agents and Inspectors to Pottsville, Pennsylvania, in June 2003 to process the licensing of the miners. Operating from hotel rooms, the ATF personnel conducted electronic background checks, took fingerprints, and assisted the miners with completing ATF forms. The Special Agent in Charge stated that the anthracite miners “were not in our purview” prior to the enactment of the SEA, making it difficult for ATF staff to know about their operations. |

To resolve the dispute, the ATF and the DOT asked the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) for a legal opinion on whether the SEA extended to explosives transportation. The OLC concluded that the DOT could exempt Canadian transportation workers from being prosecuted under the SEA because the DOT is the federal agency that oversees the transportation of explosives. However, the OLC determined that since the DOT did not have a mechanism to enforce the three prohibiting categories created by the SEA – aliens, persons dishonorably discharged from the Armed Forces, and former citizens of the United States who have renounced their citizenship – it was within the ATF’s authority to enforce these prohibitions until the DOT promulgated regulations to do so.25 That was accomplished when the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) issued a rule in May 2003 requiring “security threat assessments” for commercial drivers authorized to transport hazardous materials in commerce.

From the issuance of the OLC’s opinion in February 2003 until the TSA issued its rule in May 2003, major transportation firms voluntarily halted all explosives deliveries.26 Explosives industry group members said that because the authors of the ATF rules were not familiar with how the transportation industry operated, the regulations they wrote could have shut down explosives commerce. The confusion arose because, although the ATF previously had authorization to regulate explosives transportation workers under the Organized Crime Control Act of 1970, it did not have a mechanism to enforce this authority until May 2003. At that time, the ATF began requiring all drivers hired to transport explosive materials to complete a form certifying that they were the individuals who would transport the explosive materials from a seller to a buyer.27 The form required “drivers who wish[ed] to transport explosive materials … complete [the] form before each transaction at a distributor’s (seller’s) premises.” 28 The form caused confusion among explosives industry members because they routinely use contract carriers to transport explosives and often have no way of knowing the identity of the specific driver who will deliver the shipment to the purchaser.

In September 2003, in light of the new TSA regulations establishing DOT security threat assessment standards, the ATF stated that the requirement was “unduly burdensome and unnecessary” and discontinued the form.29 Instead, the ATF began requiring distributors of explosive materials to verify the identity of persons accepting possession of explosive materials for common or contract carriers, and required distributors to record the name of the transporter and the name of the driver in the distributor’s records.

The SEA created a new type of explosives permit. For individuals who use explosives on a limited basis, such as farmers who use dynamite to remove tree stumps, the SEA created a new “limited” permit. The Type 60 permit costs $25 and is valid for one year. It entitles permit holders to the intrastate purchase and use of explosives up to six times a year, actions that are tracked through the use of coupons.30 The renewal fee is $12. The total 3-year cost, with renewals, is $49, while the cost of a standard permit, which is good for three years, is $100. The Type 60 permit is the only permit for which the ATF issues, tracks, and collects coupons.31 To prepare for issuing Type 60 permits, the ATF spent $1.2 million to upgrade the Federal Licensing System (FLS). A portion of the money was also used to connect FLS to criminal information databases for the purpose of conducting background checks on individuals seeking authorization to access explosives.

The ATF Will Not Conduct Background Checks On All Employee Possessors Until 2006. Due to the phased implementation required by the SEA, the ATF will not conduct background checks on all Employee Possessors until 2006, when all explosives licensees and permit holders will be required to report these individuals to the ATF. Licensees and permit holders who filed new or renewal applications prior to March 20, 2003, were not subject to SEA provisions related to Employee Possessors and, therefore, are not required to report these employees to the ATF until their licenses and permits – most of which are valid for three years – are due for renewal. Therefore, the SEA would not have prevented the recent case of a convicted felon accused of stealing ten sticks of dynamite from a Vermont quarry where he worked. Although the employee had worked at the quarry for more than three months prior to the dynamite being discovered in his apartment by local police, the quarry owners were not required to submit the employee’s name to the ATF because their license application was submitted one day prior to the March 20, 2003, deadline for applications to be processed under the SEA. |

ATF Headquarters officials estimated that between 10,000 and 15,000 intrastate users of explosives would apply for Type 60 permits once SEA provisions became effective. After the second phase of SEA provisions went into effect on May 23, 2003, it became apparent that the ATF had overestimated the number of Type 60 permit applications that would be filed. Between May and September 30, 2003, the ATF issued 416 Type 60 permits, all of which were due for renewal prior to September 30, 2004. The ATF received only 372 renewal applications (a 90 percent renewal rate) in FY 2004. The total number of permit holders at the end of FY 2004 (659) represents less than 3 percent of the ATF’s highest estimates.

ATF Headquarters staff told the OIG that they believed many infrequent explosives users chose to hire contractors to perform their explosives work rather than apply for a federal permit. Additionally, ATF Headquarters staff noted that others may have applied for a 3-year permit, which allows unlimited usage of explosives, costs about $50 more than three Type 60 permits (original cost plus renewal fees), and does not require permit holders to renew their permits annually. One industry representative speculated that many infrequent explosives users did not want to deal with increased insurance costs associated with their using explosives and, instead, hired contractors.

The licensing process. To determine the eligibility of individuals applying to be Responsible Persons and Employee Possessors, the ATF developed a partnership with the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) National Instant Background Check System (NICS) Section.32 This partnership was established with the approval of the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Policy (OLP), which wrote that “… only a check conducted through the [NICS] would reveal prohibiting information regarding mental health prohibitions, dishonorable discharges, persons who have renounced their citizenship, and illegal aliens, information maintained by the FBI solely in the NICS Index.”33

To meet the first phase of the SEA, which added three categories to the list of prohibiting factors for individuals wanting to possess explosives, in February 2003, the National Licensing Center requested that the FBI begin conducting NICS background checks on Responsible Person applicants. This decision was based on the fact that Responsible Person fingerprint cards were already being sent to the same FBI facility in which the NICS Section is located – the Criminal Justice Information Services Division.

The FBI NICS System Does Not Have Access to Prohibiting Information From All States. Currently, 23 states do not share all criminal and civil case information with NICS. In these states, referred to as Point of Contact (POC) states, a state law enforcement agency queries NICS and may also query state-run databases before granting or denying a firearms purchase. Besides information related to criminal arrests, these databases may also contain information related to civil cases in which individuals were adjudicated to be mentally defective. According to NICS Section personnel, if an individual who resides in a POC state applies to the ATF to possess explosives, a NICS Examiner assigned to conduct the individual’s background check does not have the ability to access state-run databases. The fact that potentially prohibiting information may be maintained in state databases that are not accessible to the FBI, and the information is not shared with the FBI through other means, limits the FBI’s ability to identify prohibited persons because, for explosives-related background checks, the FBI only checks NICS – not any state-run databases. Therefore, NICS may not identify prohibited persons residing in POC states who apply to the ATF to possess explosives. |

To meet the second phase of the SEA, which required the ATF to conduct background checks on Employee Possessor applicants, in April 2003, the ATF’s Office of Training and Professional Development trained NLC personnel to use NICS E-Check. NICS E-Check is an Internet-based program used to query NICS.34 According to the Chief of the NLC, applications received after April 19, 2003, were processed using NICS E-Check. The Chief stated that NICS E-Checks of Employee Possessors are conducted by a contractor originally hired in mid-2002 to perform clerical work. Through NICS E-Check, the ATF contractor enters personal information from Employee Possessor Questionnaires into NICS.35

Once an Employee Possessor’s personal information is entered, the system queries three FBI electronic databases – the Interstate Identification Index, the National Crime Information Center, and the NICS Index – to determine whether the individual is prohibited from possessing explosives.36 Individuals who receive a “hit” – a possible match with a name in one of the databases – are referred to an FBI NICS Legal Instrument Examiner for a final determination on whether they are prohibited from possessing explosives. These Examiners review electronic case information and may perform additional legal research.37

During and after the background check process, NICS E-Check provides the status of the check (i.e., pending, proceed, deny, delay). According to FBI data, 88 percent of NICS E-Checks are completed on the day the check is entered into NICS. Of those, 80 percent of E-Checks are processed in about 90 seconds. Denial cases and cases that NICS Examiners are unable to finalize within 30 days are electronically forwarded to the ATF Brady Operations Branch (Brady Branch) in Martinsburg, West Virginia, for further investigation.38 (See Figure 2 for NICS E-Check completion times.) Therefore, the ATF categorizes NICS checks as “pending” until an NLC contractor or ATF Legal Instrument Examiner logs into NICS E-Check to retrieve the final outcome of the query and enters that information in the FLS. The fact that background checks are pending for some employees does not prevent a business from receiving a license. In fact, explosives license and permit applicants whose employees receive “hits” on NICS are still issued licenses and permits despite the unconfirmed background status of those employees. These licensees and permit holders are issued a Notice of Clearance containing the names of their Employee Possessors and their status — “cleared,” “denied,” or “in progress.” (See Appendix III.)

| Source: FBI National Instant Background Check Section. |

Relief of Disabilities. According to data provided by the NICS Section, between February 2003 and August 2004, 1,239 of the 53,544 individuals who applied to be a Responsible Person or Employee Possessor received denials. About 1,100 of these applicants were denied because they had been convicted of a felony. Under the SEA, individuals determined to be prohibited from possessing explosives may apply to the ATF’s Explosives Relief of Disabilities Section for “relief” from federal regulations (i.e., an exception that will allow them to possess explosives notwithstanding the prohibiting factors). As of September 1, 2004, 453 individuals had applied for relief. Of those, 299 had been adjudicated by the ATF. Of the 299 applicants, 173 were granted relief.39

Scope and Methodology of the OIG Review

To review the ATF’s implementation of the SEA, we focused on the ATF’s licensing and permitting operations, including procedures for conducting background checks and granting relief for those individuals determined to be ineligible to possess explosives. We also reviewed the ATF’s implementation of changes in inspection activities required by the SEA’s provisions. In addition, we reviewed the ATF’s plans to establish the National Explosives Licensing Center and the National Laboratory Center’s plans to implement the SEA’s requirement that importers and manufacturers of explosives provide the Laboratory with samples of their products.

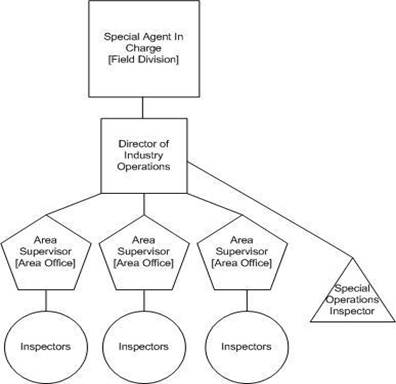

Figure 3: ATF Field Division

|

Interviews. We conducted in-person and telephone interviews with personnel from ATF Headquarters and ATF Field Divisions as well as staff at the National Licensing Center, the Arson and Explosives National Repository, and the National Laboratory Center. Specifically, we interviewed individuals from the ATF’s Enforcement Programs and Services Directorate, Field Operations Directorate, Science and Technology Directorate, Training and Professional Development Directorate, and the Office of the Chief Counsel. We also spoke with former ATF Headquarters officials, including the former ATF Acting Director.

We interviewed officials from the FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services Division and from the DOL’s Mine Safety and Health Administration.

We interviewed three explosives licensees and representatives from three explosives industry groups – the American Pyrotechnics Association, the Institute of Makers of Explosives, and the International Society of Explosives Engineers.

Field site visits. As part of our fieldwork, we conducted in-person interviews with 2 ATF Special Agents in Charge, 4 Directors of Industry Operations, 4 Area Supervisors, and 18 Inspectors at 4 of the ATF’s 23 Field Division offices – Atlanta, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Washington. (See Figure 3, previous page, for a representational diagram of an ATF Field Division.)

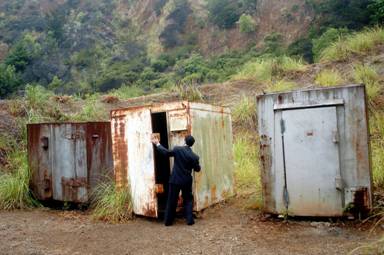

We chose these sites based on their geographic location and size as well as the number and types of explosives licensees and permit holders they oversee. While at two of these locations, we also observed Federal Explosives Licensee compliance inspections. In San Francisco, where the OIG was invited to testify before a House Committee on Government Reform field hearing concerning “Homeland Security: Surveillance and Monitoring of Explosive Storage Facilities,” we toured explosives storage bunkers (see Exhibit 2) and interviewed ATF personnel as well as state and local law enforcement officials.

Exhibit 2: A member of the OIG Inspection

|

| Source: Ron Lewis, San Mateo County Times, with permission. |

In Atlanta, we interviewed four Legal Instrument Examiners, one Program Analyst, contractors, staff, and the Chief of the National Licensing Center. At the ATF’s request, we attended an SEA training conference in Providence, Rhode Island, specifically developed for Directors of Industry Operations and Area Supervisors.

Data. The ATF provided us with data related to licensing, relief from disabilities, inspections, personnel, budgets, and explosives-related incidents. In addition, the ATF provided relevant policies, work plans, and training materials. We also examined data from the ATF’s Arson and Explosives National Repository related to bombing incidents and injuries.40

The FBI provided us with data from the National Instant Criminal Background Check System.

Background research. Our background research on the SEA and the ATF’s enforcement of explosives laws included congressional testimony, legislation, and appropriations. While we focused on the implementation of the SEA, we also identified several issues related to the regulation and safeguarding of explosives in the United States that were not addressed in the SEA but essential to ensuring public safety. Although outside the authority of the ATF, the issues related to explosives not currently subject to regulation and the limits of the ATF’s authority to inspect explosives storage facilities.

- P.L. 107-296, Title XI, Subtitle C of the Homeland Security Act of 2002.

- Geological Survey Minerals Yearbook—2002, Explosive. (Percentages add to 101 percent due to rounding.)

- The explosives regulatory functions of the ATF are found at 27 C.F.R. Part 555.

- P.L. 91-452. Partially as a result of the ATF’s growing law enforcement and regulatory responsibilities, the ATF was transferred from the Internal Revenue Service and became an independent entity within the Department of the Treasury in 1972. In January 2003, the ATF was transferred from the Department of the Treasury to the Department of Justice as directed by the Homeland Security Act.

- The SEA allowed for prohibited persons to be eligible to apply to the ATF for relief from federal explosives disabilities.

- For first-time “limited permit” applicants, the ATF is not required to conduct on-site inspections of storage sites. Instead, the ATF may verify, by inspection or other appropriate means, that acceptable storage facilities exist. For the first and second renewal of “limited permits,” the ATF may continue to verify storage by other appropriate means. However, if an on-site inspection has not been conducted during the previous three years, the ATF must, for the third renewal and at least once every three years after that renewal, verify by on-site inspection that the permit holder has acceptable storage facilities.

- Testimony of Bradley Buckles before the House of Representatives, Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security, hearing on H.R. 4864, the Anti-Terrorism Explosives Act of 2002, June 11, 2002.

- As noted earlier, intrastate purchase and use of explosives were not ATF-regulated activities prior to the passage of the SEA.

- House Report 107-658.

- ATF report, “FEL & FEP populations as of 09/29/2004 - end of FY 2004,” November 8, 2004.

- 27 C.F.R. Part 555, Implementation of the Safe Explosives Act, Title XI, Subtitle C of Public Law 107-296; Interim Final Rule. Published in the Federal Register on March 20, 2003.

- For most rules, agencies provide notices of proposed rulemaking so that the public may review the proposed regulations and submit comments. The period during which public comments are accepted generally ranges from 30 to 90 days. An agency is required to consider comments received on proposed regulations. According to the Office of Management and Budget, a Final Rule “generally incorporates a response to the significant issues raised by commenters, and discusses any changes made to the regulation in response.” ATF Headquarters officials stated that, due to time constraints and the lengthy time involved in the usual notice and comment rulemaking process, the agency decided to issue interim regulations. A Final Rule has yet to be issued.

- 68 Federal Register 6083, February 6, 2003, Transportation of Explosives From Canada to the United States Via Commercial Motor Vehicle and Railroad Carrier. The rule stated that the DOT will rely on the Canadian government to conduct background checks on all individuals transporting explosives into the United States.

- 18 U.S.C. 845(a)(1).

- Office of Legal Counsel opinion, Department of Transportation Authority to Exempt Canadian Truck Drivers from Criminal Liability for Transporting Explosives, February 6, 2003.

- 68 Federal Register 23852, May 5, 2003, Security Threat Assessment for Individuals Applying for a Hazardous Materials Endorsement for a Commercial Drivers License; Final Rule. Beginning January 31, 2005, the TSA began requiring biographical information and fingerprints from individuals wishing to obtain a new Hazardous Materials Endorsement on their state-issued Commercial Driver’s License. Individuals wishing to renew or transfer an existing endorsement will not be required to submit this information until May 31, 2005. TSA background checks include a fingerprint-based FBI criminal history records check, an intelligence-related check, and immigration status verification. However, unlike the ATF’s regulations, under the TSA’s program, applicants with certain criminal convictions will be allowed to possess an endorsement if these convictions occurred more than seven years prior to an application and if the individual has been released from prison for five years or more.

- Since 1971, the ATF imposed certain identification requirements upon common or contract carrier employees. For example, the ATF required documentation of the name, resident address, and identifying information of common or contract carrier employees. The ATF also required information related to the employee’s driver’s license number and identification document. The ATF provided the employees the option, however, to omit the latter information if the driver was ‘‘known’’ to the distributor.

- ATF Form 5400.8, revised May 2003.

- 68 Federal Register 53509, September 11, 2003. In eliminating the form, the ATF stated that it did not “believe that the elimination of this form will result in diversion of explosive materials to criminal or terrorist use.”

- “Limited” permit holders redeem an ATF-issued coupon to purchase explosives. Explosives dealers are required to submit the coupons they collect to the ATF upon completion of each transaction.

- A portion of the $1.2 million was also used to upgrade the Federal Licensing System to accept the category of Employee Possessors. ATF staff stated that most of the programming effort, however, related to the creation of the Type 60 permit and its associated coupon tracking system.

- Prior to the SEA, the ATF’s NLC personnel determined the eligibility of Responsible Person applicants by querying the Treasury Enforcement Communications System (TECS). However, TECS does not contain information related to the prohibiting categories added by the SEA. Specifically, TECS does not contain information related to aliens, persons who have been dishonorably discharged from the military, and individuals who have renounced their United States citizenship.

- Letter from Frank A. S. Campbell, OLP Deputy Assistant Attorney General, to Michael D. Kirkpatrick, Assistant Director in Charge, Criminal Justice Information Services Division, FBI; dated January 10, 2003.

- The FBI initiated the NICS E-Check system on August 19, 2002. The system was developed so that licensed firearms dealers could electronically query whether potential customers are prohibited from possessing firearms.

- Personal information entered into NICS includes name, gender, date of birth, and, if provided by the applicant, Social Security number. As of September 2004, at the FBI’s request, the ATF was preparing to include additional information, such as driver’s license number, on the Employee Possessor Questionnaires to assist with the background check process.

- The Interstate Identification Index maintains information on criminal history; the National Crime Information Center maintains information on protective orders, active arrest warrants, and immigration violations; and the NICS Index maintains information provided by federal, state, and local agencies on persons prohibited from possessing firearms and explosives.

- For example, a NICS Legal Instrument Examiner may research why an individual listed as being on supervised release is under state supervision.

- The Brady Branch was created in response to the Brady Handgun Violence Protection Act of 1993. For information on how the ATF acts on potential Brady Act violations, see Review of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives’ Enforcement of Brady Act Violations Identified Through the National Instant Criminal Background Check System, OIG Report No. I-2004-006, July 2004. (See the OIG website, at: http://www.usdoj.gov/oig/reports/ATF/e0406/final.pdf.)

- Of the remaining 126 applicants, 59 were denied relief, 37 did not respond to ATF requests for additional information and their applications were therefore not processed, 21 withdrew their applications, 8 were filed by individuals whom the ATF determined were not prohibited from possessing explosives, and 1 died before the ATF completed the review of his application.

- We examined ATF data based on the findings of an audit report, The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives’ and Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Arson and Explosives Intelligence Databases, OIG Report No. 05-01, October 2004. The report found that ATF data related to bombing incidents was more current, reliable, and accurate than data from the FBI’s Bomb Data Center data. (See the OIG website, at: http://www.usdoj.gov/oig/reports/ATF/a0501/final.pdf.)