Through its National Integrated Ballistic Information Network (NIBIN) program developed in 1999, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) deploys Integrated Ballistic Identification System (IBIS) equipment to state and local law enforcement agencies. IBIS equipment creates crime-firearms evidence images that are stored in the NIBIN database and are compared to other evidence images in the database. Matching images identify links to other crimes. By identifying links to other crimes, law enforcement authorities may identify new leads that help solve the crimes. Examples of how NIBIN has been used to link and solve crimes are contained in the ATF’s recent “Hits of the Week” publication at Appendix XI.

Every firearm has individual characteristics that are as unique to it as fingerprints are to human beings. When a firearm is discharged, it transfers these characteristics — in the form of microscopic scratches and dents — to the projectiles and cartridge casings fired in it. The barrel of the firearm marks the projectile traveling through it, and the firearm’s breech mechanism marks the ammunition’s cartridge casing. The primary markings that are unique to a given firearm are detailed below.

Land and groove markings around the circumference of a bullet: Some markings left on the side of a bullet are incidental to the machining of the interior of the barrel, while other markings, such as grooves, are intended to impart rotation to the bullet when in flight. The red arrows in Illustration 1 point to the land and groove markings on the side of a fired bullet. The red arrows in Illustration 2 point to the groove markings on the outside of a deformed bullet.

Illustration 1

|

Illustration 2

|

|

| Source: Mitretek Technical

Report 2002-CCJT-00412 |

Source: Mitretek Technical

Report 2002-CCJT-004 |

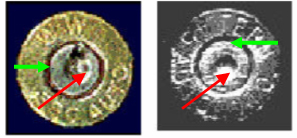

Firing pin impression on the primer face of a shell casing: When the firing pin strikes the primer of a cartridge casing, the firing pin leaves a dent in the primer. The two primary types of firing pins are center firing pins (Illustration 3) and rim firing pins (Illustration 4). The red arrows in Illustration 3 point to the firing pin dents left in the primer of fired center firing cartridge casings. The white arrows in Illustration 4 point to the firing pin dents left in the primer of a fired rim firing cartridge casing.

Illustration 3

|

Illustration 4

|

|

Source: Mitretek Technical

|

Source: Mitretek Technical

Report 2002-CCJT-004 |

Breech face markings on the primer face of a shell casing: When a firing pin strikes the primer, resulting in an explosion inside the cartridge casing, the bullet is propelled forward out of the barrel of the firearm and the cartridge casing is propelled rearward towards the breech of the firearm. The green arrows in Illustration 3 point to markings incidental to the machining of the breech that were imparted to the primer end of a center firing cartridge casing.

Extractor/ejector markings on the primer end of a shell casing: In the case of a revolver, when a round of ammunition has been fired, the bullet is propelled out of the firearm barrel and the empty cartridge casing remains within the firearm barrel until removed by the firearm user. With semi-automatic or automatic weapons, the cartridge casings are automatically ejected from the firearm. The black arrow in Illustration 5 on the next page points to the markings imparted by the mechanism that extracts the cartridge casing from the firearm.

Illustration 5

|

| Source: Mitretek Technical

Report 2002-CCJT-004 |

From the 1930s to the early 1990s, firearms examiners compared bullet and cartridge casing marks using comparison microscopes that could compare two bullets or casings at the same time. This was a very tedious process. Afterwards, photographic snapshots of the images from the comparison microscopes could be made and distributed. Generally, the sharing of such results was done locally.

In the early 1990s, the ballistic imaging and matching process was computerized. Digital cameras were used to photograph bullets and cartridge casings. Afterwards, the images were scanned into a computer, stored in a database, and analyzed using a software program. All firearms examiners with access to the computerized system could compare the marks on a large number of bullets or cartridge casings. When the computerized system was interconnected across many law enforcement agencies through a telecommunications system, like NIBIN, it permitted the rapid comparison of bullets and cartridge casings used in crimes in one jurisdiction with those used in crimes in another jurisdiction.

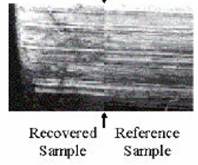

The types of comparisons made by NIBIN of the primary markings on bullets and shell casings with those of reference images are shown below.

| Comparison of Bullet Markings –

Images of Recovered Bullets Versus a Reference Image  |

Source: Mitretek Technical

|

|

Source: Mitretek Technical

|

|

Source: Mitretek Technical

|

Firearms technicians use the IBIS equipment to enter digital images of the markings made by a firearm on bullets and cartridge casings and perform comparisons to other bullets and cartridge casings entered into the system. If a high-confidence candidate emerges as a possible match, firearms examiners compare the original evidence. By minimizing the amount of non-matching evidence that firearms examiners must inspect to find a confirmable match, the NIBIN program enables law enforcement agencies to discover links between crimes more quickly, including links that would have been lost without the technology. In funding and supporting this program, the ATF provides state and local law enforcement agencies with an intelligence tool that many could not afford on their own.

Since FY 2000, $96.3 million has been made available to support the NIBIN program, of which $95.1 million had been expended as of the end of FY 2004.

Prior to NIBIN, the ATF and the FBI had separate systems for imaging and comparing ballistics evidence. To eliminate the redundancy, the agencies began working together in 1997 to consolidate the two systems. As a result, the NIBIN program was established to combine the ATF’s and the FBI’s ballistic imaging efforts into a single coordinated law enforcement system.13

In December 1999, the ATF and the FBI entered into a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) for joint agency implementation of the NIBIN program. The MOU established the NIBIN Executive Board (Board) and called for the ATF and the FBI to implement the NIBIN program. The responsibilities for each entity are described below.

NIBIN Executive Board: The membership of the Board is made up of a: (1) senior ATF executive, (2) senior FBI executive, and (3) senior executive representing the interest of state and local law enforcement.14 The Board develops and implements a global NIBIN strategy and establishes program policy regarding external relationships. In addition, the Board provides guidance to the ATF, the FBI, and partner agencies regarding automated ballistics imaging and related networking.15 The Board also convenes and oversees a working group to provide expert technical advice.

ATF: The ATF has overall responsibility for the entire NIBIN program, including:

- hardware and software development,

- deployment and installation of the IBIS equipment,

- training,

- security,

- maintenance,

- user protocols and support, and

- quality control of the NIBIN program.

FBI: Until October 2003, the FBI was responsible for the establishment, maintenance, and funding of the high-speed integrated, nationwide network that connected the NIBIN program equipment. In addition, the FBI was responsible for generating and disseminating statistical and activity reports regarding the network communication system. In October 2003, after realizing that having two agencies responsible for different aspects of the same national program was an ineffective management arrangement, the FBI relinquished its network responsibilities and authority to the ATF. The FBI’s role in NIBIN, other than that of a participating partner under the NIBIN program, ceased. Consequently, the ATF became solely responsible for all aspects of the NIBIN program.

Participating State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies

State and local law enforcement agencies participate in the NIBIN program based on an MOU with the ATF. The MOU establishes and defines a partnership that will result in the installation, operation, and administration of the IBIS equipment for the collection, analysis, and dissemination of firearms data. The agencies that sign the MOU and receive the IBIS equipment are referred to as partner agencies. The MOU must be executed before the ATF can deploy any IBIS equipment into a state or local laboratory. The ATF purchases IBIS equipment for deployment to the partner agencies, provides upgrades and service for the equipment, and administers the network over which the equipment communicates. The ATF also provides a week-long training course for new users of the system. The NIBIN partner agencies agree to: (1) support the program with adequate staffing and resources, (2) enter as much crime firearms evidence as possible into their IBIS systems, (3) share evidence and intelligence information with other law enforcement agencies, and (4) abide by the ATF regulations for use of NIBIN.17

Participating Federal Agencies

The FBI’s lab, located in Quantico, Virginia, is the only federal agency other than the ATF that has the IBIS equipment. In January 2001, the Attorney General and Secretary of the Treasury issued memoranda directing that all law enforcement agencies within those departments should enter bullets and cartridge casings found at crime scenes into NIBIN (See Appendix X). Until March 2003, the ATF was part of the Department of the Treasury. With the passage of the Homeland Security Act of 2002, the ATF’s regulatory and revenue collecting functions relating to alcohol and tobacco were realigned within the newly created Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau of the Department of the Treasury. The ATF was transferred as a bureau to the Department of Justice.

The ATF has encouraged other federal agencies to participate in the NIBIN program through one of the partner agencies or through one of the ATF servers in laboratories located in Ammendale, Maryland ; Atlanta, Georgia ; and Walnut Creek, California .

To help ensure the ATF and other federal agencies complied with the mandate of the Attorney General and the Secretary of the Treasury, the ATF initially developed two options for getting federally held agency firearms evidence entered into NIBIN. The first option asked the NIBIN partner agencies to accept federally seized firearms from their local area ATF offices for test-fire and entry into NIBIN. However, the ATF did not consider this a good option because of the funding and resources needed to obtain the ammunition to test-fire the firearms seized. The second option provided that all federal firearms evidence be taken into ATF custody, shipped to one of the three ATF laboratories, and entered into NIBIN. This option also had drawbacks, such as manpower shortages at the ATF laboratories.

To overcome the drawbacks associated with the two options, the ATF developed a pilot program that placed IBIS equipment for at least one year in the ATF’s newly formed Southern California Regional Crime Gun Center, known as the Los Angeles Gun Center (Gun Center). The pilot project required the ATF to hire an IBIS technician on a contract basis to work at the Gun Center and enter images of the ATF’s recovered firearms evidence, as well as images of federal firearms evidence recovered by other agencies in the Southern California area.

As part of the pilot program, the ATF and its NIBIN contractor (Forensic Technology, Inc.) developed protocols and procedures for test-firing and imaging all firearms recovered in the Southern California area. Protocols were also developed for maintaining and archiving test-fired evidence and associated documentation, so that the firearms evidence could be destroyed.

The overall purposes of the pilot program were to: (1) ensure ATF’s lead as “the firearms agency”; (2) maintain self-reliance and control of the ATF’s NIBIN program as it pertained to federally seized firearms; (3) develop a realistic policy regarding the Treasury mandate and ensure that it was implemented and adhered to; (4) determine the feasibility and resources for imaging 100 percent of the recovered firearms by federal agencies; (5) develop protocols and procedures on a pilot scale to implement the policy; (6) ensure that all federally recovered firearms were traced through the National Tracing Center ;18 (7) have technical representatives interact with the users on a local level; and (8) dispatch the technical representatives to a local laboratory to assist with any backlog of NIBIN entries.

For details about the Department of Justice law enforcement agencies’ compliance with the Attorney General’s January 2001 mandate, see Finding 2 in the Findings and Recommendations section of this report.

The NIBIN program network operates with regional servers in each of the three ATF laboratories. The NIBIN servers provide service to 12 geographical regions as shown in Appendix VI. As shown in Appendix VII, within each server each geographical region is divided into partitions where the firearms data from the NIBIN partner agencies is stored. The NIBIN partner agencies are assigned to regions and partitions for the purpose of performing searches and comparing firearms evidence within a particular partition in its respective region.

Regional Server: The regional server is the central data repository for the region where all images are stored and electronic comparisons are made of bullet and cartridge casing images to identify potential matches. The cost of each regional server is about $209,700. As of January 28, 2005, the NIBIN program had 14 servers, including 2 test servers (5 servers and 1 test server at the ATF’s Ammendale, Maryland Laboratory, 4 servers at the ATF’s Walnut Creek, California Laboratory, 3 servers at the ATF’s Atlanta, Georgia Laboratory, and 1 test server at the ATF’s contractor site in Largo, Florida). A photograph of a NIBIN server is shown on the next page.

NIBIN Server

|

| Source: Forensic Technology, Inc. |

Remote Data Acquisition Station (RDAS): Linked via a local area network (LAN) to a regional server, each RDAS enables users to acquire images of bullet and cartridge casings evidence through the use of an automated microscope and a digital imaging computer. The images collected by the RDAS are given a unique “digital signature” and sent to the regional server for comparison and storage. The regional server electronically compares the digital signatures and ranks them according to their degree of similarity. Comparison results are then sent back to the RDAS where they are viewed by the local firearms technician and examiner. The cost of a complete RDAS setup is about $250,400. As of January 28, 2005, the NIBIN program had 216 RDAS units. A photograph of a NIBIN RDAS unit is shown below.

NIBIN RDAS Unit

|

| Source: Forensic Technology, Inc. |

Rapid Brass Identification (RBI): The RBI is a totally portable cartridge casing system that permits the on-site imaging of fired cartridge casings. An RBI unit transmits the acquired images through an RDAS unit for processing and comparison by the regional server. Afterwards, the results are transmitted back through the RDAS unit to the RBI unit. The cost of an RBI unit is about $35,500. As of January 28, 2005, the NIBIN program had 31 RBI units. A photograph of a NIBIN RBI unit is shown below.

NIBIN RBI Unit

|

| Source: ATF |

Matchpoint: A Matchpoint unit consists of proprietary software and a desktop computer that are connected via a LAN or an RDAS unit to the regional server. A Matchpoint is compatible with the IBIS equipment and acts as an additional workspace for analyzing images. With a Matchpoint, ballistics analysis can be conducted from various locations using a LAN. The cost of a Matchpoint unit is about $32,500. As of January 28, 2005, the NIBIN program had 68 Matchpoint units. A photograph of a NIBIN Matchpoint unit is shown below.

NIBIN Matchpoint Unit

|

| Source: Forensic Technology, Inc. |

As of January 28, 2005, the IBIS equipment had been deployed to 231 sites under the NIBIN program. Appendix IV contains a list of the 231 sites, along with the type of equipment deployed to each site. The process used by the ATF to identify the sites where the IBIS equipment was deployed is described in Appendix V.

As of October 22, 2004, 888,447 records of firearms data had been collected and entered into the NIBIN program by 196 partner agencies, including the ATF and FBI.19 As of that date, the NIBIN program had also generated a total of 10,622 “hits.”20

Monitoring Participating Partner Agencies

The ATF monitors the usage of the IBIS equipment deployed to the NIBIN partner agencies by compiling a monthly acquisition report and a quarterly watch list.21 Each month, the ATF accesses each RDAS unit to determine the number of bullets and cartridge casings that have been entered at each site. The ATF reviews the data to determine whether the partners are actively using the IBIS equipment. At the end of each quarter, statistical data on entries is reviewed and compiled into the watch list by ATF staff showing low-usage sites.

After the first three-month period of low-usage, the ATF sends a “Notice of Insufficient Usage” letter to the partner agency’s head and laboratory director. The letter advises the partner agency to contact the ATF to discuss ways to increase usage of the IBIS equipment. If the usage levels remain low during the three months after the first “Notice of Insufficient Usage” letter, the ATF arranges a visit to the partner agency to discuss program participation and equipment usage. If usage is still low during the three months after the site visit and the agency’s plan is not adequate to resolve the problem, the ATF removes the IBIS equipment for use at other locations. Our concerns about the ATF’s monitoring of NIBIN users to maximize participation in the program are discussed in detail in Findings 1 and 2 in the Findings and Recommendations section of this report.

Prohibition Against Entering New Firearms Data Into NIBIN

The Firearms Owners’ Protection Act of 1986 prohibits the establishment of any system of registration of firearms, firearms owners, or firearms transactions or dispositions. This provision prohibits federal agencies from directly linking ballistic images through a centralized computer database to both the firearms themselves (a firearms registry) and the identities of the private citizens who possess imaged firearms (firearms owners’ registry). Therefore, the IBIS equipment deployed to law enforcement agencies participating in the NIBIN program cannot be used to capture or store such ballistic images.

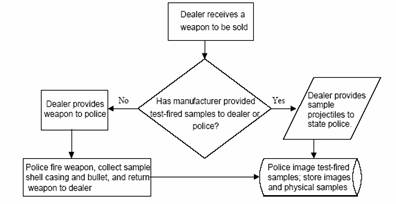

In April 2000, the State of Maryland adopted the first ballistic imaging law requiring the establishment of state ballistic imaging systems that directly link the images of newly manufactured or sold handguns to handgun owners. The law required that:

- manufacturers that ship or transport handguns to be sold, rented, or transferred in Maryland must test-fire all handguns shipped into the state after October 1, 2000, and provide a spent cartridge casing to the purchasing firearms dealer; and

- once the handgun is sold, the dealer must forward the cartridge casing to the state police, who must enter its markings in the state’s database.

In August 2000, the State of New York enacted a similar law requiring the ballistic imaging of all handguns shipped into the state after March 1, 2001 .

The theory behind the entry of newly manufactured or sold handguns is that the markings on a fired bullet or an empty cartridge casing found at a crime scene could be compared to markings in the database, thus identifying the handgun used by the criminal.

The following flowchart illustrates the process of how newly manufactured or sold handguns are processed for entry into the state ballistic imaging systems.

| Process for Entering Ballistic Data

from Newly Manufactured Firearms into a State IBIS System

|

Source: Mitretek Technical Report

|

However, in a September 2004 report, the Maryland State Police (MSP) questioned the cost effectiveness of imaging new handguns into the Maryland IBIS (MD-IBIS) and New York Combined Ballistic Information System (COBIS) state systems. The MSP’s Forensic Sciences Division determined that the Maryland MD- IBIS system had not identified any hits even though the system had been in operation for four years at a cumulative cost of almost $2.6 million. The report also stated that the New York COBIS system had not identified any hits even though almost 80,000 cartridge case profiles had been entered into the system and the system’s annual cost was about $4 million. In the report, the MSP’s Forensic Science Division recommended the MD- IBIS program be suspended. This report is discussed in further details in the Prior Audits and Evaluations section of this Introduction.

The Future of the NIBIN Program

The ATF has not made any plans to deploy IBIS equipment to additional agencies beyond the 231 agencies that already have received it. Agencies that are interested in receiving the IBIS equipment can submit a request and justification to the ATF and the ATF will consider each request on a case-by-case basis. The ATF has plans to perform annual upgrades of the IBIS software based on feedback from the users. Within the ATF, there are also plans to link NIBIN with N-Force and the National Tracing Center .22 Further, the ATF plans to work on improving the safeguards and controls within NIBIN to prevent unlawful security breaches into the system.

The potential exists for linking NIBIN with other ATF operations, such as the ATF’s regional gun centers, which serve as a clearinghouse for firearms information. The centers gather regional crime data and firearms tracing results and use analytical technology such as crime mapping and crime analysis to develop detailed information about trends in firearms-related crimes. This information helps to create investigative leads and assists federal, state, and local law enforcement in deploying resources where they are needed most.

The ATF is also conducting a pilot program called “COPS and DOCS,” which joins together health care and law enforcement professionals who recover firearms evidence and enter it into NIBIN. Depending on the program’s results, the COPS and DOCS program may be expanded. The COPS and DOCS program has been implemented at two hospitals in Atlanta, Georgia (Grady Memorial Hospital and DeKalb Medical Center). When gunshot victims are brought into the hospital, bullets from wounds are packaged with identifying information and placed in an evidence box that is located in the hospital’s operating room. The bullets are retrieved each week by an ATF agent and taken to the ATF crime laboratory for entry into NIBIN.

In September 1996, the General Accounting Office (GAO) found that five systems and one subsystem contained data that readily identified retail purchasers or possessors of specific firearms.23 The GAO reviewed two ATF systems and found that both systems complied with the data restrictions for recording or transferring firearms licensee records to a government facility or establishing a registry of firearms, firearms owners, or firearms transactions or dispositions. The GAO report noted that neither system violated the appropriation rider that prohibited consolidating or centralizing licensee records. The GAO also found the ATF had not systematically analyzed its data systems and information practices to affect the appropriation rider.

In March 1998, the Department of the Treasury Office of the Inspector General (OIG) reviewed the ATF’s IBIS system and found several management control weaknesses that needed: (1) guidance and procedures to clarify the ownership of IBIS databases, establish minimum usage criteria, and track direct and indirect program costs; (2) contingency planning for the possible reduction of future program funding; and (3) the development of results-oriented measures to assess program performance. The report also noted that these control weaknesses resulted in an incompatible, competing FBI system, and contracting procedures that allowed the IBIS contractor to imply a Treasury Department and ATF product endorsement through the contractor’s Internet advertisements.24 These conditions occurred because the ATF initially concentrated on placing IBIS systems throughout the country without first establishing focused controls and making comprehensive plans for managing use of the system.

In July 2001, the Congressional Research Service provided the 107th Congress with a brief history of how NIBIN evolved and operated.25 The report also addressed the expansion of NIBIN to cover new firearms purchases. Congress subsequently introduced bills requiring all newly manufactured and imported handguns to be ballistically imaged.

In October 2001, the California Department of Justice conducted a study indicating that automated computer matching systems do not provide conclusive results.26 Among other things, the study stated that: (1) current systems may not be as efficient for rim-fire firearms and are limited to auto-loading weapons; (2) all potential “hits” must be confirmed by a firearms examiner; (3) firearms that generate markings on cartridge casings can change with use and be altered by the user; (4) cartridge casings from different manufacturers of ammunition may be marked differently by a single firearm that may not correlate favorably; and (5) not all firearms generate markings on cartridge casings that can be identified back to the firearm.

In May 2002, in response to the October 2001 California Department of Justice’s report, the ATF issued its own report describing the use of the IBIS equipment for the NIBIN program and discussing the technical issues raised in the California report relative to the crime firearm system deployed by the ATF.27 In response to the issues raised in the California report, the ATF stated that the IBIS equipment cannot solve crimes by perfectly producing definitive matches of evidence. Further, the ATF noted that there is no substitute for human expertise and initiative by firearms examiners who confirm matches by examining the original evidence. The report stated in conclusion that no investigative tool is perfect or will be effective in every situation, but the fact that NIBIN can search a case file with thousands of exhibits in minutes provides an invaluable opportunity to law enforcement agencies that participate in the NIBIN program.

In January 2003, the California Department of Justice completed a study that evaluated ballistic identification systems and determined the feasibility of utilizing a statewide system of firearms data from test-fired and sold firearms.28 The study identified issues that needed resolution before a system could be implemented in the State of California . Those issues included: (1) further refinement and maturing of the technology, (2) using emerging technologies as an alternate to the state system that may provide a simpler and more economical means of matching a firearm to cartridge cases found at crime scenes, and (3) the need for the federal government to get involved because of the financial and structural resources that will ensure a comprehensive database.

In a September 2004 report, the MSP Forensic Sciences Division addressed the continuing problems of the MD- IBIS system, including the inability of the MD- IBIS to provide hits and to enhance or expedite crime investigations.29 The program had been in existence four years at a cumulative cost of $2,567,633. The report also identified concerns regarding the integrity of the databases. Test-fires were supposed to be included with a firearm when it was shipped from the manufacturer, but in at least one instance it was determined that a firearms dealer was actually doing the test-fires and submitting the results to MD- IBIS . The report recommended that the program be suspended, that a repeal of the collection of cartridge cases from current law be enacted, and that the laboratory technicians associated with the program be transferred to another unit. As of our audit, the Maryland program had not been suspended.

- This report is entitled Ballistic Identification Capability Modeling-A Guide for State Program Establishment and was prepared under a cooperative agreement with the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice.

- For a history of the NIBIN program, see Appendix II.

- At the time of the audit, the state and local law enforcement representative on the NIBIN Executive Board was the Deputy Commissioner of the Boston Police Department.

- Partner agencies are law enforcement agencies that have received the IBIS equipment and entered into an MOU with the ATF regarding the use of the equipment. At the time of our audit, there were 231 NIBIN partner agencies. Non-partner agencies are other law enforcement agencies that have not received the IBIS equipment. Some non-partner agencies participate in the NIBIN program by submitting firearms evidence to a NIBIN partner agency for entry into NIBIN, while other non-partner agencies do not participate in the NIBIN program.

- The technical working group consists of seven members. Both the ATF and the FBI select three members each and the Board selects the remaining member. The technical working group provides advice and recommendations to the Board on technical matters, addresses issues of current interest in the forensic firearms area, and responds to tasks directed by the Board.

- More details regarding the MOU between the ATF and each NIBIN partner agency are contained in Appendix III.

- The ATF established the National Tracing Center and gave it responsibility for tracing firearms used in crimes and recovered at crime scenes.

- Although the 196 partner agencies included the New York City Police Department (NYPD), the NYPD was not an official partner agency at the time of our audit. The NYPD had not signed the MOU with the ATF, although the two agencies were in negotiation to connect the NYPD to NIBIN. According to the ATF’s NIBIN contractor, the NYPD’s ballistic evidence is maintained in NIBIN, but the evidence is not automatically searchable by other NIBIN partner agencies. If other partner agencies have a need to search the NYPD data, the agencies submit a justification to the ATF and the ATF, along with the NYPD, will consider the request on a case-by-case basis.

- A “hit” is a successful match between ballistics images entered into NIBIN and results in a linkage of two different criminal cases. A “hit” links cases, not individual pieces of evidence. Multiple bullets and cartridge casings may be entered as part of the same case record. In this event, each discovered linkage to an additional case constitutes a “hit.” According to this definition, linkages that were derived by investigative leads, hunches, or previously identified laboratory examinations, are not “hits.” The process for collecting and entering ballistic evidence into NIBIN, and comparing and identifying potential matches to confirm “hits” is detailed in Appendix VIII.

- The monthly acquisition report contains details of the number of bullets and cartridge casing entries that have been made, and the number of “hits” that have resulted from such entries for each RDAS unit site. The activity of the RBI units is rolled into the usage data for the RDAS unit where the RBI data is submitted. The watch list shows RDAS units with low-usage during a given reporting period.

- N-Force is a case management system that is available to ATF staff. The ATF established the National Tracing Center and gave it responsibility for tracing firearms used in crimes and recovered at crime scenes.

- General Accounting Office, ATF Compliance with Firearms Licensee Data Restrictions, GAO/GGD 96-174, September 1996. On July 7, 2004, the GAO was renamed the Government Accountability Office.

- Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF), Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (BATF) Integrated Ballistic Identification System, 98-069, March 1998.

- Congressional Research Service, Report for Congress, National Integrated Ballistics Information Network (NIBIN) for Law Enforcement, July 2001.

- California Department of Justice, Technical Evaluation: Feasibility of a Ballistic Imaging Database for All New Handgun Sales, October 2001.

- Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF), Ballistic Imaging and Comparison of Crime Gun Evidence, May 2002.

- California Department of Justice, Feasibility of a California Ballistic Identification System, January 2003 .

- Maryland State Police, Forensic Sciences Division, MD- IBIS Progress Report, September 2004.